Britain and France declared war on Germany on the 3rd of September 1939; Hitler had invaded Poland two days earlier. There was a thunderstorm in Glasgow that day. Many of our respondents, who were then children, remember hearing the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announcing the declaration of war on the radio. Children had different reactions to this news across Britain. Many were old enough to know some of the consequences of World War I (1914-1918), which had ended only twenty-one years earlier, and had left lasting impacts throughout the interwar period (1918-1939). Many children’s parents had lost family members and/or had family members that were injured during that Great War. War was indeed a frightening prospect to those children.

Respondents have recalled that, as children, they heard family members being extremely upset at the announcement, and they themselves became distraught as a result. One girl remembers throwing herself on her bed and crying. Other children were convinced, on hearing the news, that it might be a good thing. One lady, in Glasgow, who was ten years old at the time, said that she was excited by the news, as she thought it meant she would not have to go to school. We have also heard of an eight-year-old Glasgow boy who was given a clip round the ear by his granny for cheering when he heard the announcement. He had confused the war with stories in the comics that he read.

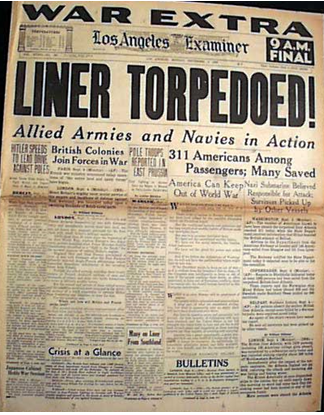

The first eight months or so of the war were known as the ‘Phoney War’; this lasted until 10th May 1940, when Germany invaded France. Yet, on the very the day that war was declared, tragedy hit Glasgow and was felt far beyond the region’s borders. The SS Athenia was a steam turbine transatlantic passenger liner, built in Glasgow in 1923 for the Anchor-Donaldson Line, which later became the Donaldson Atlantic Line. On 3rd September 1939, the passenger ship that had embarked from Glasgow, calling at Liverpool and Belfast, was sunk by a German U Boat (U-30), whilst heading for Montreal and Quebec. Passengers included North Americans, Germans, and Austrians, and families and children from Scotland. A lot of those people were escaping from imminent war. Of the 1,101 passengers and 315 crew onboard, an estimated 112 were killed, including 69 women and 16 children. Many others suffered horrific burns and other injuries. SS Athenia was the first UK ship to be sunk by Germany during WWII, with the sinking condemned as a war crime. Fearing that the USA might now join the war against them, German authorities did not accept responsibility for the sinking of a civilian passenger liner until 1946. The tragedy of the highly regarded Glasgow-built SS Athena was an immediate indication to the people of the Greater Glasgow, and beyond, of the brutality of the war to come.

Meanwhile, and also on very day that war was declared, the first air raid sirens sounded across Glasgow as it was mistakenly thought that a gas attack on the city was going to be an immediate consequence of going to war. Many people were particularly worried about the threat of bombing attacks from German Zeppelins. This caused the same mix of distress and excitement amongst children as the announcement of war had done. Some children were perturbed by the fear displayed by their parents, and some still equated the situation with a ‘Boy’s Own’ adventure. In the event, bombs were not dropped on Glasgow until July 1940, though the ensuing fear was very real. The early signs of the brutality of war were not just reserved for human tragedy. Amidst a real fear of gas attacks and deeming it to be merciful, some people had their pets put down, knowing that there were no gas masks for animals. This was supported by the Government, which issued a pamphlet urging people either to rehome pets in the country or have them put to sleep. This advice was opposed by animal charities but it was followed by residents in Glasgow and across Britain. In total, 750,000 pets met this sad fate nationwide. Obviously, many pet owners and their children would have been devastated.

Parents had been asked to register, in early 1939, if they wanted their children to be evacuated in the event of war. During the first three days of September 1939, many thousands of children, mothers, and teachers, were evacuated from Glasgow. Some went out to the countryside, as far away as Oban and Ayrshire, and some went to suburbs such as Pollokshields and Cathcart. However, only around 50 per cent of those who registered in Glasgow were actually evacuated, which was a disappointment to authorities, but the figure was better than in some other areas of Scotland.

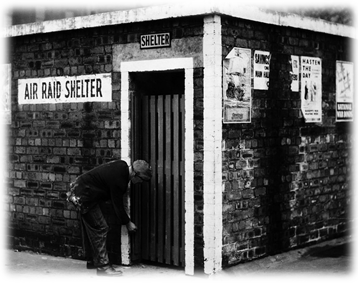

Those children who stayed home would have used various kinds of shelters during early air-raid warnings. In the first days of WWII, inter-area coordination of shelter construction was poor in Glasgow and the surrounding area, and people were often advised to congregate in the lower flats or the basements of tenements, which were strengthened with wooden supports. These areas of buildings were often used as playgrounds by children during and after the war. Children who lived in houses helped their fathers to build air-raid shelters in their gardens. Here, Morrison and Anderson shelters were issued free to people who earned under £5.00 per annum (around £350 in modern money). In one area it was recommended that if an air-raid happened whilst children were at school, or if they were fifteen or less minutes from home, then they should go home to shelter.

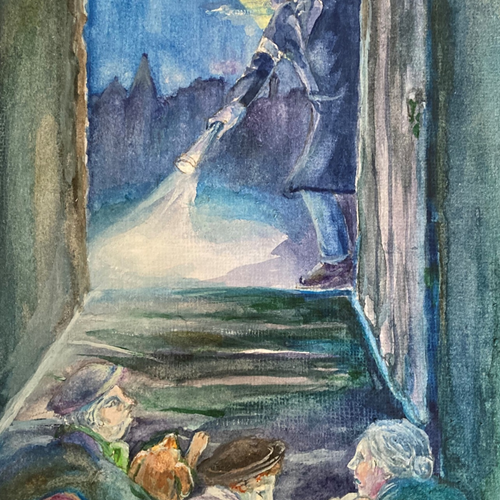

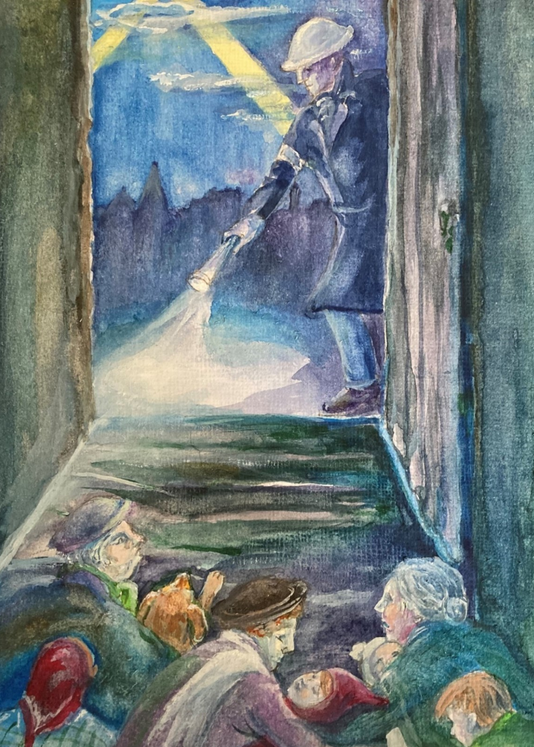

‘ARP Man’, by Joyce Kelly, Artist in Residence, Communities Past & Futures Society

Air-raids aside, children had to cope through the night-time blackouts that were imposed at the start of the war. It could be very dangerous to be outdoors in a blackout. At least one child in the Glasgow area was killed in those early days, due to the darkness. She died crossing the road and was hit by a vehicle being driven without headlamps.

There was some excitement for children when military regiments left the area to go to war; both adults and children turned out to wave them off. Thousands of people lined the streets to see the Glasgow regiment, the Highland Light Infantry, leave the city. 602 Squadron was based in Coplaw Street, in the city’s Govanhill area. It became famous in the throughout the world for its amazing record during the Battle of Britain. The Squadron was posted to Drem in East Lothian, in September 1940, from where its spitfires and brave air crews were sent to attack the German Luftwaffe, which was attacking British warships. Paisley born Archie McKellar shot down the first German plane over British soil, in October 1939 – a Heinkel HE-111 bomber over Humbie, near Edinburgh.

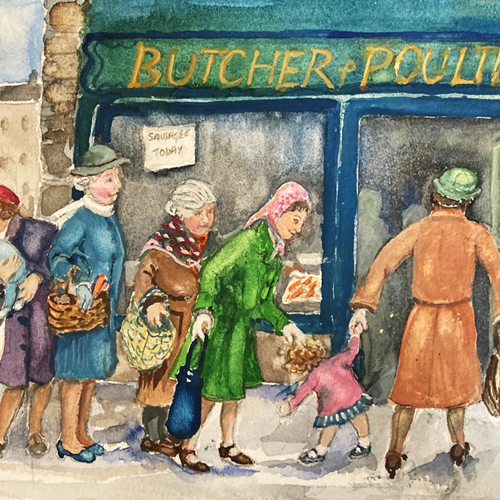

Initially, rationing was voluntary, and many people did their best to cut back on food and sweets, whilst some restaurants held ‘meatless’ days to help address shortages. Nevertheless, food and sweets became increasingly difficult to source, and formal rationing began on the 8th of January 1940. Children were issued with different coloured ration books, with different entitlements according to their age. This, perhaps more than anything, brought home to children the seriousness of war, and that life was not going to be the same for a long time.

Children across the country became aware of the threat of hostile invasion in April 1940, when Norway was invaded by the Germany. Horrifically, some youngsters overheard their parents discussing family suicide pacts. Rumours were rife, and the arrival of new families came under suspicion of being potential German spies; the reversal of this was that incomers who had fled their own area for safety were placed in the frightening position of being suspected of treason. Some people, including children, made a game out of watching people they thought might be spies. Clearly, Big Brother is not a new phenomenon.

Childhood Memories

"Air Raid and Gas Masks”

Anderson Shelter, Stirling Avenue, Bearsden, Courtesy of Nikki Anderson

Yes they were built (communal air raid shelters) some in front of the house in the street. We had a park…a field at the back. They were there for the duration of the war I would think. Nobody used them. They were smelly places.

I think some people had Anderson shelters. And we had friends who had one in their basement (air raid shelter). It was a trap door at the side of the fireplace and it fascinated me because they had the basement. It was fully fitted with furniture, a cooker and different things and I thought I’d love to play in here. It was a big house with a big cellar that’s how they were able to do that.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

The old air raid shelters they were still on the street. I never heard anybody mention that they stayed in the air raid shelters. But everybody who’d stayed in the close they reckoned it was safer to be staying in the close rather than going into the air raid shelters. The houses that had back gardens they had air raid shelters dug into the ground for maybe about five or six people

maybe more and they were covered in soil. Some of my pals had stayed in those houses.Every close had what they called a baffle wall, it was to stop having a bomb dropped in, or

shrapnel going into the close.James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

James McLaughlin, 1940s. Courtesy of his daughter, Allison O'Donnell

If there was an air raid, some of the neighbours would come down to our house because it was on the ground floor. I don’t really remember it, but that’s what my Mother would tell me. And the people you know, if they wanted to borrow sugar or anything like that, you know, well you did it. Maybe they didn’t have much. It was always tea; people were always looking for tea. Because I remember somebody coming to the house to borrow some and my Mum said, ‘Oh sorry, I’ve not got any’, and I said, ‘Yes you have Mum, it’s in that bottom drawer’ (laugh). She probably wanted to kill me.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

Air raid shelter, Wellshot Road, Shettleston. Courtesy of Charles McKenzie, ‘Lost Glasgow’ FB

We were one up with this sort of winding staircase. And when the sirens went, I remember being wrapped in a blanket, so I must’ve been quite small, and taken down. And we just went into the well at the back door of the close and we stayed there until the all-clear sounded. So, we didn’t have an air raid shelter or anything.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

Cecilia Murray aged 3 months, January 1943, with her parents Dolly and Charles Coyle. Her Father died in the war

I do remember getting wakened and taken down to the air raid shelter quite often. My Father had built a bunk in it. So. my sister and I would be taken down and we would just be put into the bunk and drop off. I don’t remember being scared or anything. Don’t remember noise.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick

Because I was born in 1940, I don’t have any memories of the war. But I do remember that outside the entrance to the flat there was a wall.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

Restored Old Linen Bank, Gorbals, which stood beside an air raid shelter during WWII. Courtesy of Ann McGuire, ‘Lost Glasgow’, FB

Also in Kinning Park, they had these shelters down the middle of Cornwall Street where they lived. And my cousin Francis got knocked down and killed there. There was hardly any cars about. But it seems some guy was driving along and waving to his girlfriend or something and he must’ve come out from behind the shelter or something.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

I remember the air raid shelters in Anniesland. It was a tenement we lived in there near Anniesland Cross and there was a square shelter type thing in the back green. I don’t ever remember going down into one because I was gone the first five years but these shelters were there for many, many years later. The shelter was for six families.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I had a brown corduroy. What they called a siren suit. Churchill used to wear them.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

Anderson shelter, overgrown, Prospecthill Place, Greenock image by Stephen McAllister

This is a recall from my Mother. It always happened on a Friday night and she would put us to bed with very warm clothes on. And I remember the sirens coming and I had no idea what it meant. I was totally innocent of any fear.

I can still picture it…we lived in a building that had two families downstairs and two families upstairs. So we shared our shelter which was all brick, with the family upstairs. And my Mother would bring whatever you could get for snacks in those days. And I remember the lady upstairs, she was a lot older than my parents and she’d put her head down and she’d be mumbling and I said, ‘what is she doing Mum’ and my Mother said she’s praying. She kept doing this when we heard the bombs coming down.

My grandparents had an Anderson shelter under the ground. I remember one time my Uncle came diving into the shelter. And he was standing outside having a cigarette and he could see a bomb coming and dove right into shelter.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

Shelter in an Edinburgh garden. Courtesy of Christine Wood, ‘Shotts History’, FB

See, everybody just went into the close. And the closes were blocked up with steel girders. And everybody just sat in the close. And the baffle wall of course was in front of the close to stop anything coming in.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

I remember having a Mickey Mouse gas mask. And I don’t know if I ever wore it, because it pulled all your hair with the big rubber straps on it. I don’t remember getting training as to how to put it on or when to put it on or whatever. That was at Calder Street School which was just round the corner from us. So I must’ve been about five.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

When the siren would come there were two types of shelters, the Morrison shelters and the Anderson shelters. One was a corrugated inverted ‘U’ sat on the ground; well, the ground was dug out. One of our next-door neighbours had that one. We had the other shelter, which was a solid steel table, you couldn’t move it. My memory of that there was of my Mother and her four sons underneath the table. It wasn’t big enough for my Dad, so he’d be sitting in a chair, up close, with his head under the table in case there was a bomb and the house caved in, at least his head would be okay. And my Mum would come downstairs, and she had blankets or pillows, and we just sat there until we got the ‘all clear’.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in The Gorbals and then Shawlands

Air raid shelters and baffle walls in a Glasgow backcourt. Courtesy of James Ross, ‘Dear Auld Glasgow Toon’, FB

My Mother grew up in Maryhill and she worked in McLellan’s Rubber Factory during the war doing war work. And she said that when the air raid sirens went off in Maryhill most of the people in that close would go down to the lower level and they would all get together in somebody’s apartment and they would try to stay there. Again, if a bomb would hit, it would have no real benefit. But at least they were all in one place. They were giving each other moral support. But she did tell me that the two nights of the Clydebank Blitz they could see the fires. And I think they did walk up to a place where they could see the flames that lit up the entire sky.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

Family gathering at grandparent's flat in Anniesland. Murdo Morrison’s father is holding him.

I too had a gas mask which when I was a little bit bigger, I can remember wearing. It was a Mickey Mouse gas mask - sort of reddish/pink colour and had a floppy nose which people would annoyingly come over and flip with the finger. I can remember after the war playing with it. Also, we had a metal bucket in the house which was filled with a fine sand and I used to sit and play with that, running it through my fingers. There was also a stirrup pump which you were supposed to use to help put out fires. Eventually these items disappeared, so maybe someone came round and collected them.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

We had the ordinary masks. The gas masks. But my brother he had one of these ones that you sat in. And he screamed every time he got put in it. And my mammy says. I’m no putting my wean in that.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

They were the people who came round seeing if your blackout curtains were working. My husband’s Mother got ten shillings fine because there was a chink of light showing from her house.

My Mum was very particular with the blackout. We had the tape on the windows. My Dad was artistic, so instead of just doing crosses on the windows, he had spider’s webs and things. It was brown sticky paper and he made patterns on the windows.

I was small but I do remember going out with my Dad. He had a good torch with a shield on it.

My most vivid recollection was when the war ended and all the street lights went on, I couldn’t believe how all the house windows with the lights on and their curtains open. It was quite miraculous, it was wonderful seeing them all.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

In the early part of 1939 it was evident that war with Germany was a distinct possibility. The newspapers were daily reporting on the delicate state of diplomacy between Great Britain and Germany. The names of Adolph Hitler, dictator of Germany, Benito Mussolini, dictator of Italy and General Franco of Spain were mentioned every day together with the British government representative, Neville Chamberlain. Mr Chamberlain is remembered best for his return from a meeting with Herr Hitler. He waved a piece of paper as he got off the plane saying, “Peace in our time”. Within a few days of historic statement, Germany invaded Poland and Britain declared war on Germany. So much for peace in our time. We heard the news from newspaper sellers, who carried large bundles of newspapers under their arms shouting, as they hurried through the streets. “war declared” An air of excitement prevailed and the hair stood out on the back of my neck. It was exciting and scary. Everyone had to be issued with gas masks. I remember that we went to the local public hall to collect ours. I think that we had to have them fitted and adjusted in the hall to ensure a really tight fit around the face and chin. The ones for babies were a weird contraption. It consisted of a base large enough to hold a baby and it had a hinged lid with a plastic window. It was also fitted with hand bellows. Operated by an adult, which was designed to supply filtered air to the infant. It was a blessing that they never had to be used as they would probably have suffocated the child. The next thing we had to have were ration books. We were issued with these at the City Halls, Candleriggs.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

I don’t really remember the day I got it, no. We all got the gas masks. Horrible things. I don’t think I wore it, I think I tried it on a couple of times but that’s about it. What a waste of money they were, really and truly, because there never was any gas, there was never any necessity for it. So to my way of thinking now that was a complete waste of money, although in the First World War, gas was used against the army. There were a lot of people gassed and it affected their health very much, so that’s probably the reason why they were taking this precaution in case the Germans used the gas again.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

I don’t remember any training. Gas masks, I didn’t particularly like them. It did feel a bit claustrophobic if you ever had one on. You got the round bit that’s got the filter and at the side its rubber, you’ve got to sort of pull it on and when you’re talking, you’re all muffled. I never had to wear a gas mask for any length of time. We always had to carry them about with us.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in The Gorbals and then Shawlands

I don’t remember the early stages of the war. I read about all that in later life but my father was an air raid warden and I sat through plenty of raids with my Mickey Mouse gas mask handy after I started primary school in 1943. I think that the Kelvin Hall was used as a factory for making barrage balloons which I think was the main reason for my evacuation along with my mother. Well, that and our proximity to the Clyde with docks and shipyards only about 1 mile away. Also, Clydebank was only about 8 miles from us and the blitz there started, I think, in March 1941.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

When we went back to living in Clydebank there were gas masks lying out everywhere. The ones for babies, they were rubber with a kind of Perspex and I think they had bellows for putting the air in for the kids…I don’t remember wearing one myself, I possible did, but I can’t remember wearing one.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

I remember the blackout. I remember we had big heavy curtains and they had to be really pulled tight or you had the man with his tin hat outside shouting ‘watch that light, get that light out’ or blow his whistle. I can remember these things although I was quite young at the time.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

My parents always quarrelled when the air raid siren sounded. My father wanted us all to go to the shelter, my mother insisted on staying in the house. She was fatalistic, and claimed that if it had her “name on it” the bomb would get her whether she was in the shelter or the house. I do not remember ever spending time in the shelter during an air raid. Mum won this argument. This, however, was in the future. As yet no bombing raids had been made on Glasgow. These were to occur the following year, 1941.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

Oh yes, yes, I remember them. You had Walt Disney ones, you know, in the shape of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. I don’t ever remember wearing them in anger, we only ever wore them for fun, because they were funny. But I never had any experience of needing to use them. For instance, I don’t remember ever having a practice you know. I don’t remember at school ever a practice of what happens if it ever gets bombed or gassed or whatever. I don’t remember that ever happening, but we had the gas masks, oh certainly, yes, but they were only fun objects.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

The bell would go, we would don the gas mask and either dive under the desk, which wasn’t all that easy, or sometimes they would say to you, ‘You can run home, say hello to your Mum and just come back again and come straight back to school, don’t dilly dally on the way’. We lived quite near the school; it was only about two minutes from the school. If you had a friend who lived a bit further, you could take them with you. It varied, sometimes it was a dive under the desk and sometimes it was a wee trip home.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

We had a gas meter under the stairs and initially we were told if there was an air attack we were supposed to hide under the stairs. But I didn’t like that idea because the gas meter, for such a little tiny lad, it was kind of frightening, this thing hissed and there was a smell of gas.

This was where we kept the gas masks. Not that we ever had to use them, but I remember playing with them later on. I couldn’t imagine having to wear one of these things, but of course, many people had to.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

Conscription of able-bodied men began and before long we were to see some of the local youths appear on leave in uniform.

Salvage drives were organised and everyone was encouraged to collect waste paper, aluminium and other metals to help the war effort. Even the railings surrounding gardens were removed to be melted down for war purposes. I remember one advertisement in the newspapers asking for the public to donate old pots and pans to help the war effort. This advert stated that even an old envelope shouldn’t be burned as it could be recycled into cardboard as a component of a rifle cartridge.

Those men who were not conscripted for the armed services because of their age or because they were unfit were drafted into the A. R. P (Air Raid Precaution) later to be called the Civil Defence. My dad was nearly blind in one eye since childhood and was not “called up” for military service although he was otherwise physically fit. He became an ARP man. Scrap metal and paper of all kinds, including books, were handed in at ARP depots. Dad thought a few books would not be missed and it would be a shame for them to be recycled. He brought some books home. A copy of Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” was given to me, which I read. I found it a rather long drawn-out story. He also brought home a few volumes of “War Illustrated” which covered the First World War. I thought it rather odd that a section covering allies in that war referred to the Italians as “The heroic sons of Italy” Now under Mussolini, they were an enemy, and were called “Wops” and other unflattering names. The Italian shops were attacked by hooligans.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

My earliest memory is of being lifted out of my cot in the middle of the night, stuffed in my pram - all by torchlight - and half carried and bumped down the three flights of stairs, along the close and into Argyle Street. Turning left into Robertson Street and crossing the road towards Robertson lane - I can still feel the pram bumping over the cobblestoned road and lane. About half way down the lane we were guided into a building and down into the basement where we stayed until the 'all clear'. But I don't remember much of that as I usually fell sleep. Pop (my grandfather) was a Fire Watcher, looking out for dropping incendiaries. My Aunt Kathleen was in the Civil Defence and would stay out in the streets helping people find somewhere safe during the bombing and attend anyone who got injured. I can see her now wearing a longish grey trench coat, tin helmet and her gas mask in its box on string and slung around her shoulder.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

My earliest memory was when I would’ve been four so that was during the air raids and it’s the air raids that would be the only thing I do remember on that occasion. Probably that’s the reason, because it was an air raid. I don’t remember anything previous to that. So, I don’t remember the actual beginning of the war as such.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

I remember we all had to get black curtains and we had to close them all the time at night. And my Father was an Air Raid Warden and it was his job to walk around and make sure there was no little bits of light coming through.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

I marched to school with one of the wee boxes, you know, that had gas masks in. The air siren going and we all got ushered into one big hall because we were all crying. I just remember my age, I don’t remember anybody older, I don’t know where they went. It was just the ones my age. I can remember blackouts being put up on the windows, black curtains, so there was no light coming in and they would shout if there was a light showing. That would be the ARP shouting ‘Put out that light, put out that light’, and the streets were black and some places had what they called baffle walls. And when I look back on it now, I think it was some kind of electric sub stations or… and something happened and it didn’t blast right out when I think about it now. We didn’t know what it was, we just used to play round about it. I remember going out to Birkenshaw to my Uncle’s. I don’t know if we were evacuated out there or stayed for a wee while and I think I went to school out there. When the air raids came at night time, I remember mostly. The air raid shelters were in Glasgow Green and I’m sure they were dug away down. I had big brothers and sisters so I remember my brothers taking me on their backs or on their shoulders and there was a big blanket thrown over you, you know, to keep you cosy you know, to go to these air raid shelters. That was near the People’s Palace they had that. And I remember they had a barrage balloon there as well just beside it. If you were facing it, it was there to your left. It was a bit that was all cordoned off, it was all covered up, so it must’ve been something to do with the army in there. The air raid shelters, the men would stand at the mouth of the air raid shelters and smoke. I don’t know how the aeroplanes didn’t see us with all the men. It’s a wonder we didn’t get killed with all the smoke. I remember getting wakened during the night, hearing the ‘bang, bang’. I remember eventually we got an air raid shelter in the back green and it was only bare bricks and my Mum just hated going in it. She said you were safer in the buildings, they were stronger.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok