‘Evacuees’, by Joyce Kelly, Artist in Residence, Communities Past & Futures Society

Britain’s plans for evacuation during WWII have their roots in the loss of life, on the home front, caused by Zeppelin bombing during WWI. One thousand five hundred people died as a result of this bombardment. The bombing of Guernica, in 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, then solidified the need for an evacuation plan in the minds of the British government. Children from the Kindertransport, which started in 1938, were evacuated to Glasgow, as were a small number of the total of the children evacuated from Guernsey in 1940. Some of those children were fostered in families living in the Southside of Glasgow.

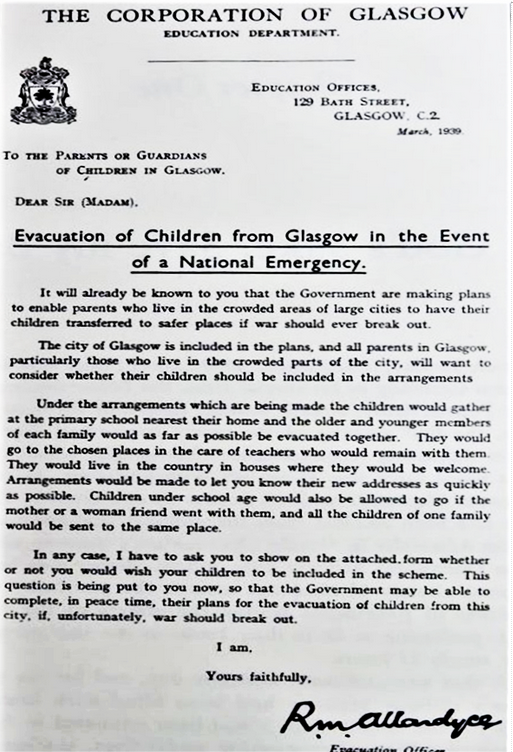

When WWII seemed inevitable after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, the British authorities began preparing for the evacuation of children, mothers and infants, and infirm people, from areas that were considered likely targets for bombing and gas attacks. In May 1939, people were required to register for evacuation. It was a voluntary scheme. The order came to ‘evacuate forthwith’ on the 31st of August 1939 before war was declared. The government planned to evacuate three and a half million people in the UK but ultimately only evacuated one and a half million. Posters appeared urging parents to evacuate children. Nevertheless, some people preferred to go into the uncertainty of the wartime situation with their children at home, especially when faced with the prospect of seeing them leave and there been no end to the separation in sight. Some people were also suspicious of the official reasons for evacuation. The government had poster campaigns to encourage evacuation, and the press published photographs of happy evacuees to encourage families to evacuate family members and children. Glasgow children were pictured with refugee children in Perthshire, taking in the harvest. Though small than anticipated, the evacuation was still the largest migration of people that the country had ever experienced and the first time in British history that mass evacuation was deemed necessary. The operation took place over three days from the first day of September 1939. And was an immense logistical task. The operation was code named ‘Operation Pied Piper’.

Many evacuees returned to their homes in late 1939 and early 1940, after Britain’s declaration of war against Germany failed to bring bombings and gas attacks; this period was labelled the ‘Phoney War’, but it was followed by further evacuations in 1941, this time in the wake of the Blitz bombings and the threat of V1 bombs. Evacuations to Canada and Australia continued despite the torpedoing of the SS Athenia in September 1939, which had private evacuees on board. When the SS City of Benares was torpedoed in September 1940, also carrying evacuees, the short-lived policy of these evacuations ended. By the conclusion of WWII, three and a half million people, mainly children, had experienced evacuation.

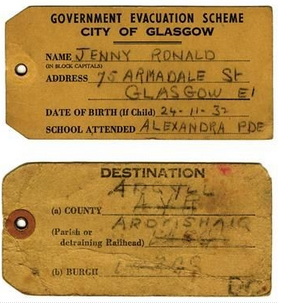

The children who did get evacuated would usually gather at their local school to begin their journey by train, bus or boat, and teachers were frequently involved in organising evacuations and sometimes accompanied the children. Tiny, labelled suitcases contained their incredibly basic luggage, which consisted of a toothbrush, a change of underwear, and a few other essentials. They also carried their gas masks, often wrapped in paper and string. Some people arranged their own private evacuations to relatives in the countryside.

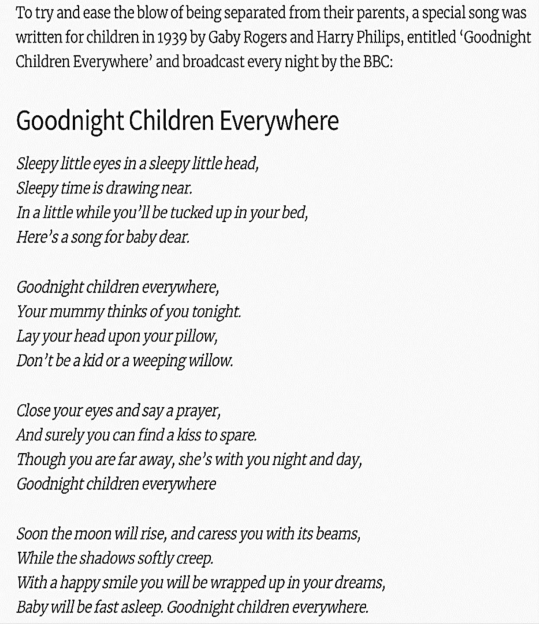

The Women’s Voluntary Services for Air-Raid Precautions, precursor to the WRVS and the RVS, helped with the complicated coordination of evacuation. Local children were also often involved to work in reception centres for evacuees. Residents were obliged to take in evacuees and could be fined if they refused. Those who took them in were given an allowance for their care. The result of these measures was that some people resented their new young charges, or took them in only to supplement their own meagre income.

Evacuation in Scotland in early September 1939 consisted mainly of evacuations from Edinburgh, Rosyth, Glasgow, Clydebank, Dundee, Inverkeithing and Queensferry. The Department of Health for Scotland had been preparing for it, like the rest of the country, from early 1939. Glasgow saw only half the expected number evacuate on the first day, but this rose to 70 per cent by the third day. In total, up to 190,000 people were evacuated from Glasgow. This was one of the most successful evacuations in Scotland in terms of numbers. Many people were evacuated to suburbs such as Cathcart, Knightswood and Pollokshields. Some were even evacuated to Clydebank, and others to rural Lanarkshire, Perthshire, Ayrshire, Rothesay and Kintyre, amongst other places. Almost 120,000 left Glasgow at this point. Most were home by Christmas 1939, due to their being no mass bombing up to that point. By the time of the Clydebank Blitz on the 14th March 1941, only twenty thousand people in Scotland were still evacuated.

From Spring 1941, in the wake of the devastating Clydeside air-bombings, Greenock, Port Glasgow and Dumbarton were evacuated, along with some from the original Glasgow areas, although vast numbers of Glaswegians chose not to evacuate on this occasion. Fifty-eight-thousand of those that evacuated during this period remained evacuated for months or years.

Evacuees had a wide variety of different experiences across the UK and the world and throughout the war. Some had difficult and occasionally horrific times. Most felt homesick, and children could be separated from siblings, which they found even more hard. They could feel out of place as they did not understand the local accent or dialect, and the locals found it difficult to understand them. Children, on occasion, felt unwanted by their foster parents. These children were sometimes made to eat in different rooms from their hosts and were generally treated poorly, as if they were barely tolerated. People were known to exploit the grant money they got for the children by taking in far too many evacuees, and some were known to use the children as free labour. City children were often stereotyped by country and towns’ people as thieves, and as being dirty and louse ridden.

There were occasions when it was difficult to house children due to these false perceptions. ‘City kids’ were the last to be picked at reception centres, or were only reluctantly taken in when walked round the doors by supervisers insisting that they be lodged. This attitude haunted Glasgow children, and the MP for Glasgow, Mr Buchanan, felt compelled to stand up for them in the House of Commons, as comments were made by other MPs about their ‘verminous’ state.

Children were sometimes neglected, and worse, by their hosts; some wrote begging letters to their parents pleading to be taken home, others ran away, sometimes making their own way home. Evacuated children from Glasgow were seen jumping on trams to get back home from Renfrewshire, and on trains to return home from a placement in Moffat.

Other children had positive experiences whilst evacuated and were treated like family members from the offset. These children were supported and adapted well to country life, helping around farms and with other types of work. Some were known to stay connected with their foster families for many decades after the war ended. There are also examples where they stayed with their foster parents after the war, perhaps after having lost their birth families, and others stayed with or returned to foster communities and married their young wartime sweethearts. Good homes during the war could mean that children found it difficult to adapt to life back with their original families. Long absences meant that children who were every young when evacuated, often did not recognise their parents or feel that they belonged with them when they returned home. The situation of private evacuations and those sent overseas brought its own challenges and advantages. These experiences, good and bad, would often stay with those who were evacuated throughout the rest of their lives.

Childhood Memories

“Evacuation”

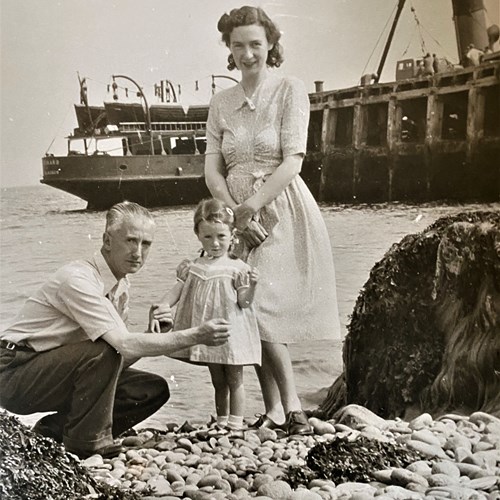

So that’s the story. That’s my first memory of the war. But then my Father, he must’ve had inside knowledge because he decided that Millport was not in any of Hitler’s plans. And he decided that we would move during the war to Millport. So we left, and I think we stayed there for two or three years when I started school. So I’ve got fond memories of Millport. I don’t remember it ever raining in Millport. It was always sunshine. And of course, as evacuees. I mean we weren’t officially evacuees because my Father had decided we would go there. But we were classed as evacuees and we weren’t very popular on the island. The children I mean, I don’t know about the adults. Coming from Greenock there was all sorts of things like coming across gardens with grass and apple trees and pear trees. The part of Greenock that I come from these things didn’t exist. So, we were known as the apple stealers. So we weren’t too popular. But I enjoyed being there.

I have to tell you a story (from Millport during the time he was evacuated there). Milk also got delivered by horse and cart and my brother, my older brother he got the job of, the dairy gave him a job when he finished school, in the afternoon, of returning the horse to the farm that it was hired from. Which would have probably been half an hour’s walk with this horse. Just the horse, not the cart, just the horse. Anyway, he had an accident of some description. I think he broke an arm and so the dairy said that I could take the horse back. Now bear in mind I could only have been about five or six, and here was me leading what I thought was a huge horse. It was probably a pony or something like that. I imagined it was a huge Clydesdale horse, which it wasn’t. Anyway, two hours later I hadn’t turned up at the farm with this horse, because I was actually scared of the horse and if it stopped to eat, I stopped. There was no way I was going to pull this horse, so two hours later they had to send out a search party for me and the horse. That was an experience I’ll never ever forget, this horse and pulling it back to the farm.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

I was evacuated to Milngavie (pronounced Millguy) but went with my mother and not any other children. We stayed in ‘Invermay’ which is a mansion in Milngavie which still stands today. I did not see or meet any other evacuees. My mother and I travelled to Milngavie by train and I remember arriving at the station and the long walk to the house. The house was owned by John Dunlop Anderson (Director of Education for Glasgow) who was unmarried and lived with his sister whom I only ever knew as Miss Anderson. I arrived home, by train, in the same way we had left, on the night before I started primary school at Overnewton Primary School. I believe that many people living in the suburbs and the countryside offered accommodation to Glasgow refugees, I didn’t know any incoming refugees from other parts of the country.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

Hugh Livingston as a toddler

Well, the evacuation was because of the heavy bombing that occurred in the neighbourhood. And there was some serious loss of life and I think my parents said this is not the best place for a small baby. And my Mother’s sister had a house out in Fintry and so we were moved out there. I’ve no memory of the actual period, but I do remember subsequently being involved in local little summer sports events and having races and things like that. So I have memories of Fintry that started then and then over the years it was my Aunt’s place and we visited it many times and I was actually christened in the Church in Fintry. So that was on my birth certificate. That shows that I was christened there.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

When I got evacuated. The war had just started and we all got evacuated. Our school shut down and I think a teacher used to come to my Mum’s house and there was a few kids in the street were allowed into my Mum’s flat. It was only a room and kitchen. Only once do I remember a teacher calling and all he talked about was the birds and the bees and I never saw him after that. So after twelve, I got no education, that was me finished.

The first evacuation was to Kilbirnie and after I think we stayed there for about, I would say roughly about six weeks. Oh no, it might have been more than six weeks because I went to school in Kilbirnie. I can’t just remember exactly how long, but it wasn’t awfully long and then we came home. And then the war was getting quite serious so we got evacuated again to Stewarton. And we stayed in Stewarton until the war…, or my Mum stayed in Stewarton for quite a while.

A lovely little village (Stewarton where he was evacuated for a second time). Lovely little village. Nice people. We got on so well with all the locals. We all had girlfriends. And then I joined the Sea Cadets in Glasgow. And I worked in Glasgow and travelled back and forward on the train. I was just a boy in Peter Fisher’s dry salters in Mitchell Street.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

I was at Kelvinside Academy day school in Glasgow from 1938. So one year after I joined the school, the school was evacuated from Glasgow on 1st September, two days before the war broke out. And it was evacuated to Dougray Lodge in Arran which was a small hunting lodge on the west coast of Arran which was very uncomfortable. Although, I don’t remember very much about it.

We saw, or one of my classmates saw, the bombers flying down Loch Lomond, low, to get to Clydebank. They had come from Norway, I think. And one of the boys swears he could see the pilot of the German bomber.” “They dropped bombs on Inversnaid Hotel, which is a little village on the east side of Loch Lomond. People don’t know of it, but I think there were decoy fires which was something we did although at the time it was said it was just something they did, burning the heather. And for whatever reason they dropped bombs on the Inversnaid Hotel which was shattered. And we went over, the school went over, in the Princes May, one of the Loch Lomond steamers a day or two later to pick up bits of shrapnel for mementos.

The other memory was being taken to the railway station, the Arrochar/Tarbet railway station. And I can’t remember which year this was. And watching the King coming off the train, probably to go to the Arrochar torpedo unit or submarines, but he was visiting somewhere. We all waved and cheered. That brought a bit of excitement to life.

Apart from that, it was a sheltered existence. Small school, no sporting team events. We did have a local school. The Tarbet School. We didn’t have much dealings with them oddly enough. You would’ve thought the two organisations would have co-operated but it was very separate and we had no real dealings with the locals. I think a couple of boys from Arrochar came and joined us for a year or two I don’t know what’s happened to them. Played tennis on the tennis courts at the hotel and played around as I say, played football, soccer and probably five a side amongst ourselves.

At the end of the war we came back. We had come back on holidays during the war, we came back for Christmas, for summer holidays. And lived in danger as there was danger in Glasgow. I don’t know why they thought we had to be evacuated for safety from January until June and September until December but back we came. And I think I remember only one lot of raids when we sheltered under the stairs. Which was the traditional way of sheltering in these old Victorian houses. But I don’t remember anything more than that of the impact of war on myself, except that each of my siblings in turn went off.

We had evacuees. It was a family from south Glasgow who were billeted and were living in our house. We gave up part of the house to them. I think it was by government decree. My Mother was quite happy to have the company instead of rattling in a big old Victorian house. Having had five children.

Ralph Risk, born 1932, brought up in Pollokshields, Tyndrum, and Tarbert

On Friday 1st September 1939, two days before the United Kingdom declared war (on Sunday 3rd September 1939), Iain, (aged 12and 1/4) and Tom (14 and 1/2) were evacuated in school parties with children and teachers from Clydebank to Garelochhead by train.

We were initially billeted with Mr and MrsAllison, wholived in a cottage in the grounds of a large house named Dhalandhui, where Mr Allison was gardener. Later we moved to stay with Miss Agnes Cameron, Elderberry Cottage, and later still, with Miss Cameron's sister, Mrs Stalker and her husband John at Daisybank. The Stalkers were both perhaps aged about 60, Mr Stalker having retired from his adjoining joiners and undertaker’s business. We were resident at Daisybank (attending Hermitage Academy in Helensburgh Monday to Friday via the school bus) on the night of Thursday 13thMarch 1941.

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

For almost the first five years of my life I lived in Fintry. We had a little house there and we were there to get away from the bombing and stuff like that because it was going to be in Glasgow.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

My cousin, Jim Gallagher, he got evacuated from London, from the London Blitz. And he ended up staying in Clydebank with our family, him and his Mum and Dad. And when we got bombed out, he ended up in Rothesay with us. Jim and I were more or less like brothers because we were roughly the same age.

Obviously, I was only eighteen months old during the blitz and we were evacuated to Rothesay so I was probably about five or six when I can recollect things. One of the things I do remember that stands out in my mind is down at front where the ships came in and I remember seeing the sailors’ hats floating in the water and H.M.S. cork lifebelts. Because at that time they were made of cork. Until I got back to Somerville Street I wouldn’t have known what a bombed out place was, but I did after I got there.

We were evacuated because the house had suffered some damage. One or two closes up from us were bombed out. In Bruce Street where the baths were some of the buildings were flattened but the baths survived. I imagine that’s why we were evacuated to Rothesay…Some people went to Fife and some went further North.

There was woods behind the house we stayed in and we were always up there. Jim stood on a wasps nest and the two of us got completely covered in wasps and there was a man, he got hold of us and there was a pond and he put us in the pond to try and kill them. Then he took us home and my Mother and his Mother and they took all the dead wasps and the live wasps off us.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

My family was very large. My Mother was one of thirteen children. So she had lots of brothers and sisters, many of them in Glasgow. So they’d be coming to the same spot.

We had the little house until I was a late teenager so we often went there. .But we stayed out there during the war years.

We had very happy times in Fintry, despite the war. They had a town hall and every Saturday night was a get together for anyone who wanted to come, children too.

My father had to go to work every day and see to the business and every time he came home, he was bringing more relatives to get them away from the threats of bombing.

Eventually, jumping forward many years they had a garage that my brother turned into a little tea room because there was nowhere to eat in Fintry. It only opened at weekends because by that time we were back in Anniesland.

So they were fun years, bad years, but fun.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

We were evacuated to down in Dumfries and Galloway for the first three weeks of the war and then we came back. And within the next year in Trossachs Hotel, a big hotel in the Trossachs and that was, not the whole school, but as many as parents wanted their children to go.

I remember the day we went on the train down to Stranraer or thereabouts. And me and my friends had a picnic with our sandwiches. And me and my little friend Moira started eating them before we’d even left the station.

I remember these children coming from the Channel Islands to I think our local church and then they were farmed out to different families. And I remember partly because I still knew a little bit about him. I remember a little boy and I remember the family he went to. We never took anybody but they took this little boy and kept him forever and he grew up. I don’t know about him now but he went to school and they paid for his school.

I can even picture these volunteer parents and the children that came all the way from the Channel Islands. These were children much less privileged and lucky than me.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

Tom and I resumed school on the Monday after the raids. We kept in touch with the folks by letter - not returning to Taylor Street for a weekend until perhaps August. We stayed in Garelochhead during part of the school holidays -July/August on Mamore farm, Rahane on the Gairloch side. The farmer was Willie Goodwin, whose mother was a close friend of our landlady Mrs Stalker. He delivered our milk. We worked at hay-making and turnip thinning for 10 shillings (50p) a week, and enjoyed it.

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

The folks at home were fairly deprived, without tapwater, gas, electricity on the Saturday. However, on the Sunday,father's uncle, Jim Mcinish and Aunt Hellen (nee Macduff), (who of course had heard about the Clydebank raid on the radio and had tried to phone Mum, Dad and Uncle Willie, at Taylor Street,) arrived by car and insisted on taking the folks back to Johnstone to stay with them. They did this and stayed for 6 weeks, while Taylor Street house was repaired. During this time, father and Uncle Willie travelled to work, Monday to Saturday in John Browns via the Renfrew ferry. When number 8 was habitable the folks returned to Clydebank.

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

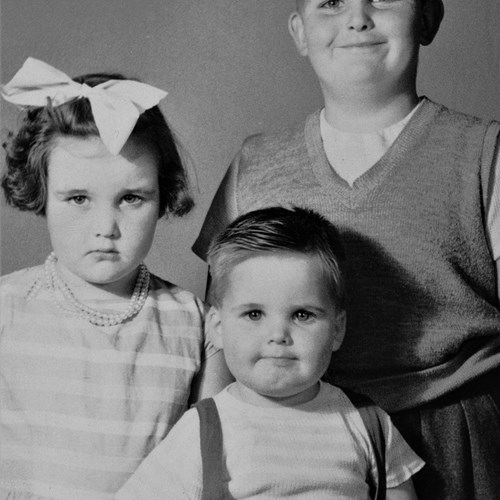

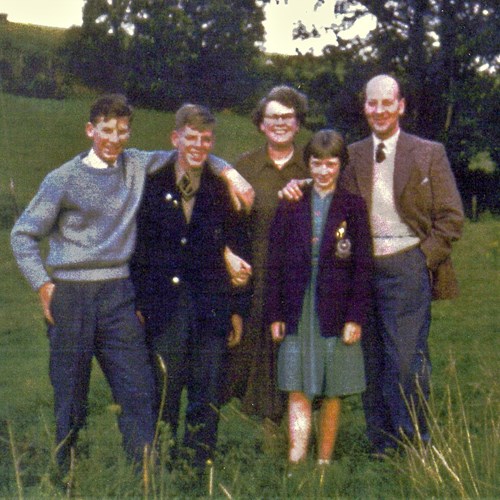

The late Dr Iain Blair MacDuff as a child, with stepmother Lizzie Bothwell and brother Tom at the Blair’s house, 8 Taylor Street Whitecrook. C.1940/41 after the Clydebank Blitz

I am not sure of the date but we were evacuated to Twechar before the Blitz, I believe. That was my Mother and my brother and me. I believe after a little while my Mother decided if one of us was going to get killed we were all going to die so she took us home. I think my brother went to Ghiga- not sure if that was later. Robert was 7 years older than me.

Matilda Jane Holmes, born 1937, brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh, and other places

We were in a Church hall in Milngavie. I just remember and a lot of the women standing in a big queue to get washed at the washing house or whatever it was… and my Father coming and taking us over to Kinghorn.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick

When we arrived in Kilmarnock we were assembled in the station into a “crocodile” three or four abreast, and marched through the town to a hall where we were allocated to the folk who were to become our guardians. I still remember the local folk lining the pavements, some with handkerchiefs held to their eyes, and all looking at us with emotion and compassion.

John Power

It was a quarrel with Willie (his brother) that led to us leaving the McGhee family. It happened that we were arguing in the front garden of the house. We were being observed by the McGhee’s neighbour. At one point I smiled at her as she stood at her window. I remember picking up a pebble from the driveway and saying to my brother. “I am going to keep this as a souvenir for you, you wee midden” We called each other “midden” when we were annoyed. It was a commonly used word at the time. The neighbour had observed and heard us and I thought no more about it. We were wakened at about 7am by the sound of Mr McGhee talking loudly. He was saying something about “well they are not going to be staying here much longer” When we came downstairs for breakfast after he had left for work we found Mrs McGhee in a tearful state. I enquired what was wrong. She said that that her neighbour had reported that I had said that she kept her house like a midden. This was a complete distortion of the facts and I told Mrs McGhee what had actually been said. She was quite inconsolable and I was hurt and angry at the neighbour. I told Mrs McGhee that under no stretch of the imagination would I have said such a thing. I reminded her that I came from a three-apartment tenement flat, with five kids, and my father did not earn a big wage. In comparison, Mrs McGhee had a palace.

Mrs McGhee may have been distraught but so was I. After what had been said I knew that relations would never be the same again. Looking back on it now, I can understand that Mrs McGhee would be inclined to be influenced by a neighbour she had known for years. She would be inclined to believe the neighbours word against the word of a kid, of recent acquaintance, from Glasgow. I have often wondered if the neighbour ever realised how she had caused such unhappiness between the McGhees and a young boy who was an evacuee.

John Power

We were sent to Moffat but we didn’t like it and Flo had some money I don’t know where she got it from but she got us back on the train to Glasgow the next day and we went home. (Flo elder sister and Bruce the younger brother of David).

Davie Walker, born 1934, brought up Bridgeton, Glasgow

I do not remember if we were taken to our new home or were collected. I do remember that Mr and Mrs McGhee and a younger couple were in the house when we arrived. The house reminded me of my Aunt Maggie’s house in Troon. Aunt Maggie or “Tish” as my father called her lived in a semi-detached and her family were grown up and in good jobs. Her house was spotless with good quality furniture. The McGhee’s house was similar. Everything was spick and span. Everything was neat, there were no children to make the house untidy. I thought that this was a beautiful house and that we were lucky to be living there. Before going to bed that night and every night thereafter we had to take a bath. This was unusual for us because, at home, we had a bath once a week

John Power