Glasgow still had some of the worst slums in Europe at the end of the Second World War. The war and resulting shortages of builders and building materials had brought house building to a low level, with only 4,882 houses being built by the corporation between 1940 and 1945. There had also been few repairs to existing housing stock during this period, much of which was in poor condition. An official report estimated that fifty thousand new houses would need to be built each year in order to solve the post-war housing problem in Glasgow. In 1951, Glasgow had more overcrowding than other large cities in Britain. Surrounding towns, such as Greenock and Clydebank, had similar and sometimes even more acute problems due to the extensive bombing which these areas had suffered. Greenock’s housing issues ranked amongst the most severe in the country at the end of The Second World War.

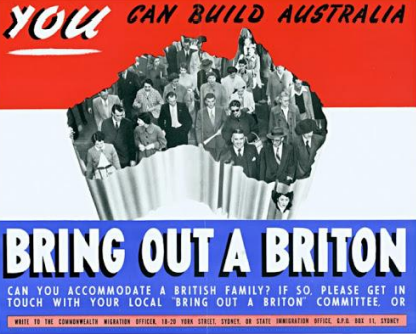

A post-war wave of emigration from the British Isles to various countries provided a solution to the housing problem for some. Although not all emigration from Glasgow and the surrounding area, or indeed, Britain, was prompted by housing problems. A few of our respondents immigrated for work reasons, and some for love. The Australian Assisted Passage programme began in 1945. Adults were charged ten pounds and children travelled for free. Over one million people used this scheme between 1945 to 1972. New Zealand had a similar scheme, which started in 1947, and over seventy thousand people from the British Isles had taken it up by 1971. Over half a million people immigrated to Canada in the twenty-five years after the Second World War. Other popular destinations included South Africa, Rhodesia, Nyasaland and the USA. For those who stayed at home, options varied.

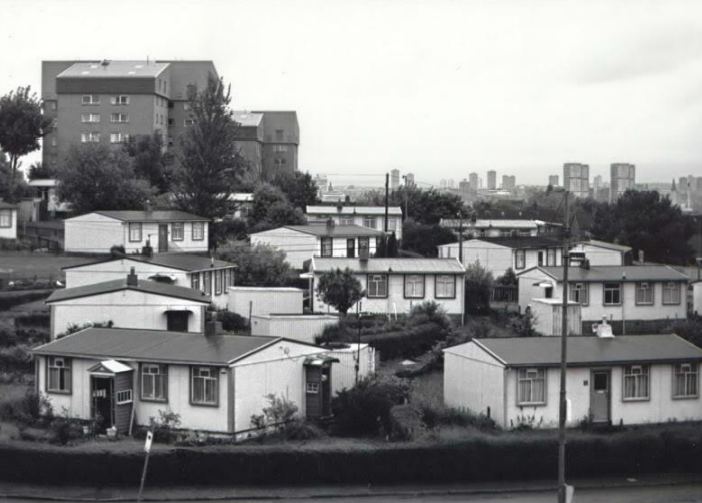

As was the case during the war, grass roots movements, and actions that were encouraged by the Independent Labour Party, and the Communist Party, resulted in people squatting in buildings, and in former POW and army camps. The latter had also been suggested by the Secretary of State for Scotland, in 1943, as a solution to the wartime housing crisis, but his ideas were not taken on board by the Government, which was more focused on creating new housing after the war. In Scotland, people are thought to have entered army camps as early as 1945, before the war ended and a year before this happened in England. They were motivated by poor existing housing, the lack of housing stock, and having to live in overcrowded situations with relatives. Many made improvements to their surroundings, including modifying former POW and army Nissen huts with new stoves and partitions that created more rooms. Others put up curtains, and created small gardens. The Department for Health, and in some cases the local Corporation, eventually started charging rents after deciding that some income was better than none. Some of the camps were still squatted into the 1960s. Children often enjoyed these camps as they were frequently surrounded by countryside in which to play. Glasgow Corporation did not put many of the ‘squatters’ (an official term disliked by many who lived in the camps) on the list for rehousing, which naturally caused delays in those people being given permanent housing. These mavericks were given verbal support from other members of the public who sympathised with their predicament. A couple of our respondents remember seeing people living in these camps in post-war Patterton in East Renfrewshire, Pennylands in Ayrshire, and Greenock.

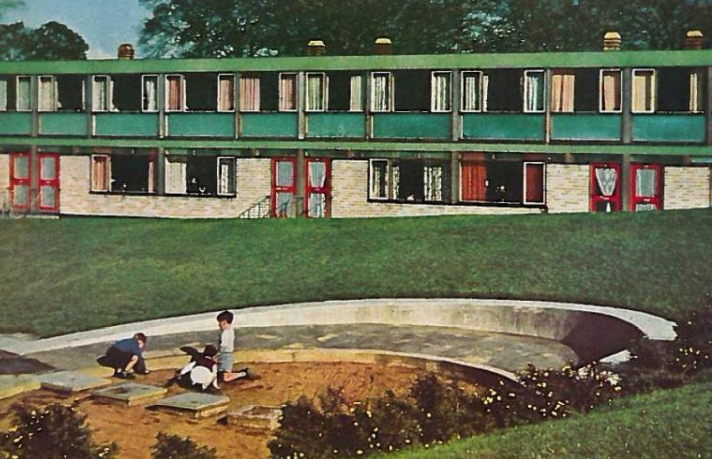

Plans for prefabricated houses, or prefabs, as a way of abating the housing crisis, were put in place by the Government as early as 1942.There were more than 3,210 prefabs built in Scotland between 1945 and 1966. Families with young children, and families of returning servicemen, were at the top of the list for these houses. Many people enjoyed the comparative luxury of the prefabs, which were pre-constructed and made of materials such as steel, asbestos and corrugated iron. They had inside toilets and mod cons, such as fridges and washing machines, which made them very popular with people who had come from poor housing conditions. Their quality did vary though, and there were some issues. Problems stemmed from them having flat roofs and plumbing complications, that included toilets that flushed hot water. A couple of our respondents lived in prefabs, and one very clearly recalls her childhood in a corrugated iron construction in Scotstounhill, Glasgow. She remembered that they were of a brilliant design, and she felt that nobody ever voluntarily left their prefabs and that everyone loved them. She also said that the surroundings provided great freedom for the residents, and that there was a thriving community around her. She also said that ice developed on the windows in the winter, but pointed out that most people put up with that. Around fifty per cent of the prefabs built during this time were demolished by the 1970s, but some still survive.

Housing estates were built on the outskirts of Glasgow in the late 1940s and 1950s, in places such as Drumchapel, Castlemilk, and Easterhouse, in an attempt to deal with the housing crisis. In Greenock, estates were built at sites such as Larkfield, Pennyfern, and Brachton, amongst others, with a total of five thousand new homes built by the Corporation there by 1960.These places were often seen at first as wonderful, by people coming from housing that was overcrowded and often had outdoor toilets. Now they had front and back doors, and baths. One of our respondents remembers that when he was a child, his house in Drumchapel had a bath, and water was heated by the fire until it got an immersion heater in the 1960s. He also remembers there being wee plots of land available for local people to grow food. Some people reported missing their old communities because people from the close-knit tenements of old were sent to various parts of the city. A lack of amenities was also cited as a reason that these housing schemes fell short of the mark. Shops were sometimes sparse, and, in some cases, people had to travel into Glasgow to pay their rents. When the Housing (Repairs and Rents) (Scotland) Act, 1954, was introduced it brought with it the demolition of three 3,200 homes in Glasgow, in just ten years. This increased the need for estates and brought about the building of high-rise flat blocks from the 1950s, into the 1960s. High-rise flats were often poorly constructed, and some would say, ill-conceived, eventually causing issues such as damp and isolation. Others have fond memories of the flats which brought, at first, improved housing for many. Residents recall that there was a sense of community in these flats for many years.

New Towns were also built in an attempt to cope with the housing problem. East Kilbride was the first, in 1947, followed by Glenrothes in 1948, and then Cumbernauld in 1955. Two more New Towns at Livingston and Irvine were built in the 1960s. New Towns had many of the same benefits and disadvantages of housing estates. They also had the advantage that they often attracted large employers, such as the Inland Revenue and Rolls Royce.

Despite the introduction of new housing, the 1961 census showed that there were still 11,000 homes in Glasgow that were unfit for habitation.

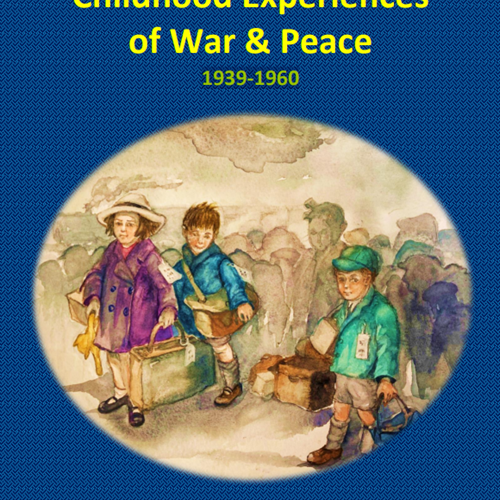

Childhood Memories

“Post-war Housing”

Our prefab was the corrugated type. We had a side garden, a front, and a huge back garden. The land had recently belonged to a farm and indeed the rest of the farm was still across the road from us. This was where the farmer had grown vegetables so it meant the soil was really, really good. And we could grow just about anything in that garden, the soil was amazing. We had three doors. We had a back door from the living room, a side door from the kitchen and a front door from the hall. There was two bedrooms. There was a living room. A kitchenette which you could eat in as well. And we had a fold out table that could go down or lie flat against the wall. So, you could either have loads of room in the kitchen or you could eat there as well. Now we had a fridge which came with the house and not a lot of people had a fridge in 1948/49. That was one of the advantages of living in a prefab, having a fridge. We had a coal fireplace and pipes going through into the bedroom which supposedly kept it warm. I suppose there was a bit of heat when the fire was on. Out the back we had what looked like an Anderson shelter, but it wasn’t, and that was where we kept the coal. I don’t think anybody ever voluntarily left their prefab. Everybody loved living in them. You had your own door. You had a big garden. You were comfortable most of the time. I mean in winter you would get ice inside the glass but most people in Scotland got ice inside the glass in winter. They were very functional houses and we certainly loved it. I don’t know anyone in a prefab who didn’t love it. The bathroom had a separate toilet. So, there were no fights when someone was using the loo and somebody else wanted a bath or a wash. The toilet in these were separate from the bathroom. So that was a good bit of design as well.

Marlene Barrie born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

When I think about it, I really had quite an idyllic childhood. I mean we may not have had a lot of money but we had space, we had gardens, we had the farm across the road, we all had bikes. We’d all go away for hours and hours in the summer on our bikes sometimes quite far. Sometimes in the farm across the road the farmer would let us ride his horses. We had dingle’s pond and we used to skate there in the winter. Sometimes I used to go over to Crossmyloof Ice Rink. We really had lots of things to do and lots of space to do it in and lots of freedom. You could be out all day. You knew adults would be looking out for you wherever you were. Or checking if you were doing something wrong. There didn’t seem to be the same fear around as there is now. As long as you came home in time for your tea that was the main thing. I think the space and the freedom we had was just amazing.

Marlene Barrie born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

East Kilbride was started as a New Town in 1947 and one of my school pals and his family moved there. We were on the list for rehousing but it never happened. Prefabs were put up in many locations mostly outside Glasgow. I did not know or see any homeless in our part of Glasgow.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

My father was demobbed in 1945. I was born in 1946. And we moved into the prefab in 1948. So, for that two years we had lived with my mother’s parents in Kingsway. And in that house, as well as the two sons that still lived there, was another brother and his wife and his…one of his children. So, people were crammed in, usually to grandparent’s houses. You know a room for each family or something. And that was quite common. So, to get the prefab…My uncle who also lived with my aunt, his wife and child…They managed to get a prefab as well in Lincoln Avenue which wasn’t that far away. And another uncle who got married later, after the war, he eventually got a house in Drumchapel. But if it hadn’t been for our grandparents having a house that was a reasonable size then they would have been struggling. But they must have been quite cramped when they all lived together in that…It was a four bedroomed house but when you think of…there was my grandparents, there was the two sons that still lived with them, there was my mum and dad and me, eventually. There was my uncle his wife and their kids so…Yeah it would have been pretty cramped. So, it was pretty desperate that they built these prefabs I suppose. I think mainly they were for people returning from the services. I think they certainly had priority for them. I know my mum said to me that the day they said they were releasing these prefabs she was up at the crack of dawn. And she was at the front of the queue to make sure she got her name down for one.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

What I really wanted to talk about was the sense of community there was in this little group of twenty-four, twenty-three prefabs. Because. I think, the children were all about the same age. All the parents were roughly about the same point in their lives as well, roughly age wise. And there was a real sense of community. You know, the parents used to put away… something like sixpence a week would go into a fund. And then twice a year they would have a party. So, in the summer we would have a picnic outdoors. There was a community sort of square in the middle of the houses. And so everybody would do baking and make things. And they would set up trestles. And they would have this big, sort of community picnic. Mrs Ferguson used to bring her piano out into the square. My dad would play the piano. The men would have races. The kids would have races. We’d play musical chairs. And that was like sort of our summer party. We also did things like that for The Coronation. But we had a party like that in the summer every year. And then at Christmas time we’d have a party somewhere for the kids. And there would be presents for the kids and Santa and all that kind of thing. So, there was a real kind of feeling of people working together and helping each other out. I mean not being in each other’s pockets but kind of always being there. And these little functions that we had now and again sort of kept everyone socialising.

Marlene Barrie born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

It was a tenement, a typical tenement of the time. It was a room and kitchen. We were on the top flat and I’m guessing it was built in the late 1800s. And what they’d done was, at some point, they had built a column of toilets up the back to try to modernise it. Because there was no indoor plumbing at all. We had no bath inside. We had no toilet, and so each landing had a shared toilet and that was it. So if you wanted a bath you basically put a tub in front of the fire and you heated water in a kettle and you filled it up. Now you just hop in the shower and it’s no big deal. But it wasn’t that easy in those days. Especially if you had three children. We had a very old-fashioned range - it was a fireplace in the middle and cooking rings. That was the sole source of heat in the flat and we had a boxed-in bed in the kitchen. And my sister and I shared that until my brother came along, because it was warm in the kitchen. They would do what they called ‘banking the fire’ and put what they called ‘dross’ on the coal fire to try to keep it going overnight because if it went out, in the morning. We usually didn’t buy kindling. What we did was we’d take newspapers and make long tubes out of them. We’d roll them up and then we’d twist them to what we call firelighters. And we’d put some coal on top of that and they would burn long enough usually to get coal going because we weren’t going to go to the store and buy kindling.

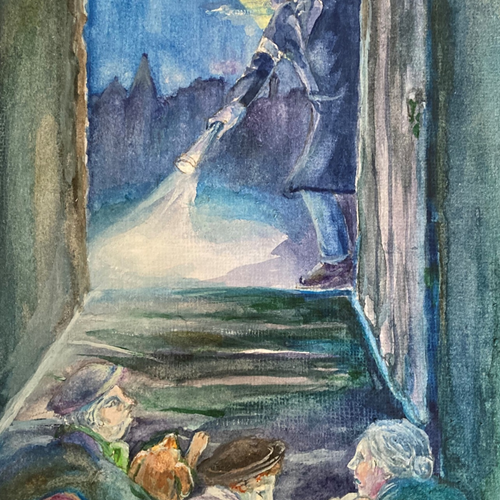

Every once in a while, chimneys would catch fire because what people would do to get the fire to ‘draw’ they would put a big newspaper in front of it. This was to try to stimulate the draught but every once in a while, the paper would go ‘up the lum’ as they say. And every once in a while, there was a lot of creosote and soot up there and it would catch fire and it was scary because it would be like a blast furnace. And then you got worried that it would either set everything on fire or they’d call out the fire brigade because then you would get into trouble.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

We lived in a prefab. And we left the prefab in Burnhouse Street in Maryhill and we moved to Oran Street to a tenement. I was three, three and a half. I can still remember wee bits of the prefab. When we moved to Oran Street it had no garden. At least we had a garden in the prefab.

I do remember the prefab vividly. Our back garden, at the end of the back garden, was a canal. And my Mother was terrified that we would fall in the canal. So she had my reins on and a big bit of rope on the back of the reins, which was tied on to the clothes pole so I could only get so far. I couldn’t get to the water. In those days, the canal was used commercially and boats used to come up it like Para Handy’s Vital Spark. The wee sort of Clyde puffers. And they’d be towing barges going up to I think it must’ve been McLelland’s Rubber Works and all that. We were near a bend near the aqueduct that went across Maryhill Road. And these wee boats used to blow their whistle, you know the ship’s horn, and I was terrified. I couldn’t get into the house because the rope was at its tightest and I was running and my wee legs were going. But I couldn’t get away from this noise. I remember that. I’ve never ever forgot that.

When I was about three-and-a-half, we moved to Oran Street and in a tenement. And the close…sharing toilets and all that. Whereas in the prefab we hud a bathroom and an ice box. Wasnae a fridge but it was an ice box. We never had any of that in the tenements. So, the prefabs were great.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

We lived in Ibrox, and we stayed in 47 Hinshelwood Drive but we had a room. My Granny had the apartment in the tenement. It was three stories high and we were at the top. My Granny, she worked at Ibrox in the Rangers Football Club which was only fifty yards away. And nicely she gave us a room when my Dad came out the army. That’s where he met my Mother up in Craigellachie. The way they met each other was, the nearest he came to conflict in the war, was he backed his lorry into my Grandfather’s fence and my Grandfather came out and gave him a row. And my Mother happened to be there, and that’s how he met my Mother. So they got together, they married and I was born and then we moved as a family down to Glasgow. And I presume as there was no accommodation we moved in with my Granny.

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

I would be about ten or eleven. We moved up to Pollok by then and when children played outside and all that as against nowadays. And it might have been the summer holidays and we had walked away up near Thornliebank/Spiersbridge on the old Stewarton Road and up the Stewarton Road. We walked by this ex-army camp because it was all the Nissen huts and all around them was gardens. And I remember seeing people there and I think they had washing out. And it was years later I found out it had been a German Prisoner of War camp.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

I was fourteen and a half when we went to Castlemilk to a new house there with our own bath and toilet.

Our house was getting demolished and my Mother would’ve loved to have stayed in the New Gorbals. And we hung on and hung on but she was easily fobbed off, you know… a woman on her own. And couldn’t shout the way some could and the close was getting emptier and emptier. You know there was hardly anybody living in it. So it was scary living up a close that used to have loads of people in it. So, she just accepted the offer in Castlemilk and we went there.

I remember lifting the letterbox and looking through. It was a sunny day and it looked lovely. It was just two bedrooms, living room, bathroom and a kitchen. It was painted, the walls were a pale grey and pink, quite fashionable.

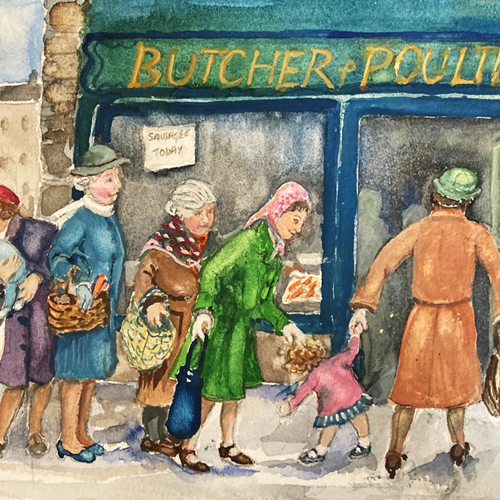

There was a wee row of shops up the top. A butcher, a chemist, a Galbraith’s. Yes, there was shops. But you tended to look down on your local shops. My Mother would say don’t go to that butcher, go to the one at Croftfoot. I’ve still got that snobiness about butcher-meat because of my Mother.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

Post War we began to see more exotic fruits than had been available before. It was 1947 before I ever saw a banana for example. Butter became available and brand name margarines. Rationing ceased and much more and varied foods were available.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

The tenement in Oran Street was a normal tenement. We stayed in the close. There were four families in the close. Four single ends they called it. We had a room and kitchen at the front. My Mother used to go out every two or three weeks and wash the close. And I had to go to the wee shop across the road, I was about five, to get what they called a slab of pipe clay which would be about the size of a mobile phone nowadays. And that was what my Mother used to put round the border, the edge. So, your close was your pride and joy. Because it was always washed and fresh pipe clay put down. That’s what people were like in those days. Everybody knew everybody. There wasn’t that much traffic in the streets, you could go out in the street and play football. There were buses, but hardly anybody had cars. The only people that did have cars or vans were people that got them supplied by their employer.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

It had three fairly substantial rooms, a kitchen, a large sitting room with a coal fireplace. My parents had a bedroom and there was a very large room overlooking the corner of Otago Street at Gibson Street for my brother and I. And there was a slightly smaller room which was my sister’s room and that was overlooking Otago Street.

All, or much of our childhood before the summer was spent playing games in Otago Street. which was a very secure area because it was almost like a cul-de-sac. Of course, we had the trams that ran up and down Gibson Street so we didn’t have to go too far for transportation.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

There was seven of us in the one room. And somebody, I think it was my Father maybe, wrote to the Daily Record or somebody said write to the Daily Record. And they had an article about it, and within a month we were offered a house in Pollok. So, we moved to Dormanside Road.

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

The period at the end of the Forties and start of the Fifties was a fairly happy time for me. My brother and I had a loving, employed father and mother and plenty of aunts and uncles. We were well fed and clothed and I loved playing in what I considered a huge flat, which in fact it was. At that time unfortunately in Scotland in general and the city of Glasgow in particular we had the most horrendous overcrowding with dreadful sanitation, poverty, unemployment, with all that follows from that. There was an extreme lack of proper housing. Many soldiers were returning from the war and had to join their wives who were staying children with their parents. Many thousands went to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the US at this time.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow

Only in as much as the necessity for prefabs. The prefabricated houses that they built and that was purely as a result of homeless people.

I do remember people living in Nissen huts and prefabs.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

I remember the prefabs I think they were near Hampden. There was a whole lot of prefabs built there at Mount Florida but I was never inside one.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

Eventually we found a flat of our own at the top of the hill in Hillhead Street just up from the University. I can remember going up to view the flat with my mother and my uncle (second eldest of my mother’s brothers) Duncan's wife. The flat I thought was huge. It was no 44 Hillhead Street and of course was empty except for a very old fashioned "candlestick” telephone. I would be between two and a half and three at this point.

Our top floor flat was a wonderland for me. We had huge rooms which you would have needed a private coalfield/oilfield to keep warm. Times must have been hard and it was a very cold period but I of course was blissfully unaware of this. Creeping into the kitchen one day I wanted to see my wee brother lying in his "Moses Basket" on a chest of drawers. I caught hold of the edge of his basket and tumbled him out onto the floor. I have to say that Alan, as he is called, seems to have suffered no ill. Looking out over the city at night it was a magical place of lights everywhere and we lived at the top of one of Glasgow’s high spots. Our streets and closes were lit by gas at that time and the "Leerie" came round to light the lamps and to turn them off again when it was light. They gave a funny pale greenish light. The lamplighter always had a word for me. I can remember that we still had ration books and my mother and my aunts had big discussions over what to buy. Probably because of the first war my brother and I were the only children out of the eight. This was probably caused by the fallout of the first war, e.g. not enough men left to go round, and those that were left had no real job security.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow