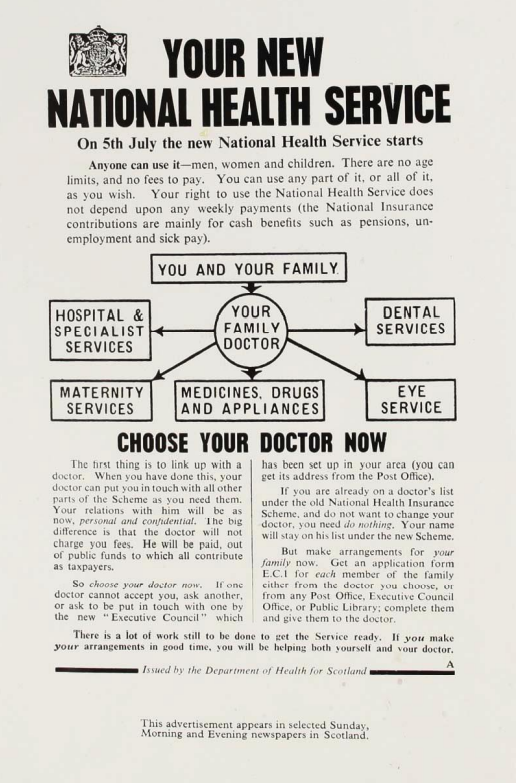

5th July 1948 was a momentous day in British history as the National Health Service (NHS) was finally introduced. This was the culmination of years of bold and pioneering planning to make healthcare no longer exclusive to those who could afford it, but to make it accessible to everyone. The National Health Service, fondly named the NHS, was launched by the Minister of Health, Aneurin Beavan, at the Park Hospital in Manchester; it was the first step toward creating a strong and reliable healthcare service. However, the formation of the NHS was the product of years of challenging work and motivation from various figures, who felt that the current healthcare system was insufficient and needed to be revolutionised.

Prior to the creation of the NHS, anyone requiring a doctor or access to medical facilities was expected to pay for their treatment. In some cases, local authorities ran hospitals for local ratepayers, an approach which originated from the old poor law. By 1929, the Local Government Act amounted to local authorities running services that provided medical treatment for everyone, and in 1937, Dr A. J. Cronin’s novel, The Citadel, provided further momentum to address the inadequacies and failures within the healthcare system. He had observed the medical scene greatly and the book helped prompt new ideas about medicine and ethics, which inspired both the NHS and the ideas behind it. There was a growing consensus that the current system of health insurance should be extended to include dependants of wage earners, and that voluntary hospitals should be integrated. When war broke out in 1939, discussions around reform were put on the back burner, despite the growing issue of lack of health provisions in Britain. By 1941, the Ministry of Health was in the process of agreeing a post-war health policy, with the aim that services would be available to the entire general public. In 1942 the Beveridge Report put forward a recommendation for health and rehabilitation services, which all parties across the commons supported. Eventually, the cabinet endorsed the white paper put forward by the Minister of Health, Henry Willink, in 1944, which set out the guidelines for the new NHS. The idea of a health service that was funded from general taxation, not national insurance, and where everyone was entitled to free treatment, was taken on by the next Health Minister, Bevan, who brought about the NHS in the form we are now familiar with.

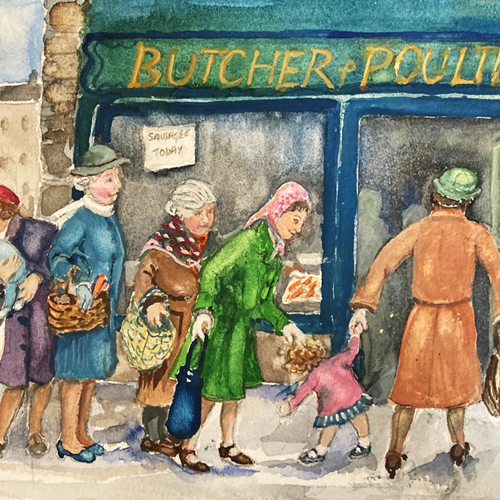

In Scotland, the NHS changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people who until then had been unable to afford even the simplest medical treatments. Prior to the NHS, patients had to face an unequal treatment system of voluntary and municipal hospitals. The purpose of most voluntary hospitals was to treat the sick and poor, and unlike in England, most did not charge patients for treatment. Affluent patients were treated at home or in private nursing homes. Consultants usually worked unpaid in the voluntary hospitals, relying on outside practise for their income. Municipal hospitals ran by local authorities were a product of the welfare system created by Poor Law legislation and carried the stigma of the old workhouse. In the 1920s and 1930s, waiting lists in Scotland were growing longer. In Edinburgh, the waiting list for gynaecology had reached 2,800 by 1929, and the Scottish Board of Health’s Hospital Services Committee stated that there were many people in Scotland who were unable to get the hospital treatment they needed. For these people, a shortage of beds meant prolongation of their suffering, and action was often delayed beyond the point where effective treatment was possible; many people died before being admitted to hospital. By 1939, the old system was teetering on the verge of financial collapse and, in wishing their successors well, the directors expressed the hope that the spirit of public service, which has built up the voluntary hospital service, would continue to animate the Health Service of the future.

Parliament passed the National Health Service Scotland Act in 1947 and it provided a uniform national structure for services, which had previously been provided by a combination of the Highlands and Islands medical services, local government charities, and private organisations, which in general were only free for emergency use. The new system was funded from central taxation and did not generally involve a charge at the time of use for services concerned with existing medical conditions or vaccinations, carried out as a matter of general public health requirements. Within the first month, at least 90 per cent of Scots had access to a family doctor for the first time in their lives. In its inaugural year, the NHS in Scotland provided free eyeglasses to half a million people in need, while another half a million people received free dentures. However, some have argued that Scotland had already established itself as a home of medical excellence prior to the introduction of the NHS. Scotland was central to some of the biggest advancements in modern medicine; therefore, it was no surprise that the introduction of a free universal healthcare like the NHS owed much to the developments in Scotland too.

Scotland continued to be at the forefront of many medical advances. In 1958, Glasgow produced the first practical ultrasound scanners, which unlike X Rays, carried no risk of radiation, and unlike other experimental ultrasound models, did not involve patients getting into a bath. The Glasgow model proved simple to use and cheap enough to be affordable by hospitals in the developing world. Its initial success was unlocking the secrets of the womb, showing how babies grow and develop, and it was refined over the years to help diagnose a range of diseases by providing images in 3D colours.

As well as advances in diagnostic equipment, Scotland was also leading the way in terms of medical research and treatment schemes. In 1950, a Medical Research Council study by Sir Richard Doll and Sir Austin Bradford Hill revealed the link between smoking and lung cancer. This led to the Health Minister, Iain MacLeod, publicly accepting the link at a press conference in February 1954. Around 80% of the adult population were smokers at this time, with Scotland having consistently higher rates than the rest of the UK. In 1951, rising levels of tuberculosis, and a chronic shortage of beds and nurses, led to a special scheme for Scottish patients to be treated in Swiss Sanatoria, as public concern and media coverage contrasted Scotland’s increasing waiting lists with the empty beds available at reduced rates in Switzerland. The first flights to Zurich began in June 1951, in a UK wide scheme for 400 patients to be treated at Davos and Lysine, more than half were from Scotland. It was publicised as a first triumph for an egalitarian NHS, as British people were able to enjoy the best tuberculosis facilities in Europe that were previously only available to the rich. By the time the scheme ended in 1956, more than 1000 Scots had been treated.

Childhood Memories

“Healthcare”

My Mother and Father always said thank goodness for the N.H.S. I would have been about two when the N.H.S. came in. So, they were always telling me about what it was like. Paying for doctors and only getting what they could afford. When I was three, I got pneumonia and I was in hospital for about three weeks, I think. And of course, penicillin had come out by that time and I was fine. So I used the N.H.S. when I was very young since I was three. And I’ve used it for the rest of my life since then. And I worked for the N.H.S. as well.

Marlene Barrie, born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

The Uncle who was the ship’s surgeon. He bought into a practice as a partner when he was demobbed. And actually, the town where he was, he did such a lot for the town, that they named a street after him when he died. That was in Fife (Chamber’s Street, Cowdenbeath).

I can remember sitting in the doctor’s surgery. I had a very bad vaccination, smallpox vaccination that I got at school and it poisoned. And I think it had been a dirty needle that was used because I remember going down to the doctors and every night for a week or ten days. He burned the wound with what he called blue stone. It was a blue stone and I can remember gripping my Dad’s hand. The pain was excruciating to get rid of this vaccination. So that would be before the Health Service I think.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

Well, we always went to the doctor’s office, where the local shops were. And the doctor would come to the house.

I remember one story. My sister was sick with pleurisy and the doctor came to the house. And he wanted to put her on medicine, a special one that was just new. And my Father wouldn’t let him because his idea was, he was going to make a guinea pig out of my sister. So she didn’t get it and fortunately she did get better with whatever they used for medicine. But that new medicine that the doctor was wanting to give her was Penicillin. Which would’ve cured it right away.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I remember that I had my tonsils out in Aberdeen. But it was in a private nursing home just down the road from where we lived. My memory of that was I had been promised ice cream when it was done and there was no ice cream, there was only custard, and the memory is still there. Whereas my brother had his tonsils out at home in Glasgow in the middle fifties. And in fact, he had to have them, there was obviously a stump left, taken out again a few years later.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

One of my cousins had polio and was on an iron lung and he almost died, so that was very close to home. Another cousin had tuberculosis when he was about 17 and he was sent out to Switzerland, publicly funded. He was sent there to recover from tuberculosis. When I worked, I worked for a while in a chest clinic and we still had tuberculosis patients, although it was into the ‘70s by then. I think we were all grateful for the polio vaccine. Especially when one of your cousins had actually got polio and another one had got tuberculosis.

Marlene Barrie, born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

Because of my Mum’s background (she was a nurse) she would often make reference to a really new antibiotic that had been brought out by a company M. &. B. And I think it was one of the first antibiotics that was ever used in the N.H.S. So, because of my Mum’s background and my Father’s. He had been a medic in The Royal Army Medical Core. So, the background was one of being used to listening to stories about how things had been and some of the older remedies that had been used. And my Mum and Dad still used when I was a child. Things like the kaolin poultice. So, it was all these things that were spoken about. I think the N.H.S. must’ve made a huge difference.

Maybe when I was about three or four, I recall being taken to a doctor’s surgery. And I think what I remember most was the strange smell. Because in those days the doctor’s surgeries were also the pharmacies. And some of the doctors made up their own medicines on the spot. So you would see mortar and pestle dishes. It was really quite strange. The one that I went to was Oliver Springer, he had a surgery in Maryhill Road but he used to make up a lot of medications himself. So there was always that sort of herbal smell when you went into the surgery.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

What I do remember was my Mother’s Mother, my Granny Steven. I remember them talking about my Granny’s neighbour. I don’t know what it was and my Granny saying this woman’s never away from the doctors. And it was because the Health Service had started and wasting it for everybody else, never away. And that would obviously be the late ‘40s.

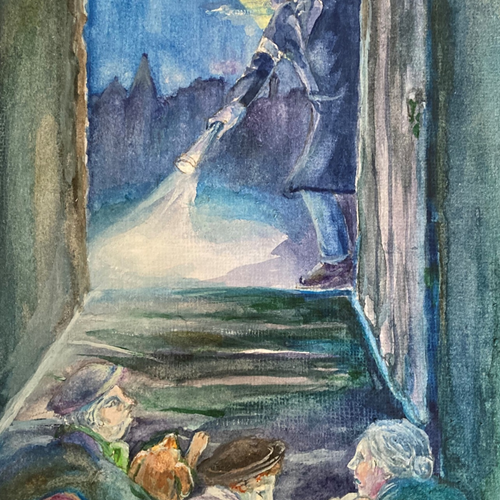

What I do remember was when I was wee before the Health Service. I remember my Mother taking us when I was ill, I don’t mean seriously ill. And down at Buchan Street. And in it there was a building and the organisation that was in the building was called a medical mission. It was basically to service the poor prior to the Health Service coming in. And I remember my Mother taking me there at least one time.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

In fact, he actually came to our house in Hyndland (Dr Cameron). When I had my tonsils removed and my tonsils were removed on the kitchen table under a kind of a local anaesthetic of some kind. I only have the vaguest of memories of that. It sounds terrible but I didn't suffer from it. As far as the NHS is concerned, no, I was unaware of where the medical care came from. I suppose I only learned about that in later life when I was a teenager or so.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

There were health visitors, we called them Green Ladies because they wore green uniforms and special hats and they would come in to check up on you. Especially if you had young children. They were intentioned and tried to help and I think they probably did help. But again, there was this intrusion of authority. You know, there was a sense of working class people being sensitive to being judged. But I think it was the Government trying to make sure the children had basic nutrition.

I remember when I was in hospital that there was a lot of fresh fruit and obviously things designed to try and build us up.”

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

We were very well look after, after the war. After the Labour government got in. We got cod liver oil and orange juice. I used to go to Florence street clinic. I don’t know if they took blood. I don’t remember. I’d of screamed the place down if they’d done that. I don’t know how they knew. But they said you’re anaemic. An my Mother…they used to give her jars of malt extract to give me.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

1947- I remember my Mother being delighted because she was getting family allowance, not for me, not for the eldest. I think it was seven and sixpence she got for my sister and the same for my brother. So that would be her getting fifteen shillings extra. But she used to let it mount up and that would go towards our holiday. The same with the dividend in the Co-operative. She used to let it build up.

It made a difference because a doctor’s visit in those days was half a crown and half a crown was hard to come by. So you needed to be really ill before you got taken.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

I remember we had a doctor in Pollok Street. And I don’t know whether you paid him or not. I can’t just remember too much about it. I visited the doctor a couple of times. A dentist, I remember a dentist, I stayed with my Granny at that time. And she gave me a shilling on a Saturday morning to go to a dentist at Glasgow Cross and you stood in a queue. The queue was right down the stair on a Saturday morning and the people were coming out with their hankies over their mouth, blood dripping through. And that was your dentistry for you. I can remember the school dentist that was the cruellest damn thing. Going to this school dentist at the Gorbals round the corner from the Palace Picture House. And I can remember, I don’t know what age I would’ve been, can’t remember what age I would’ve been. And I remember getting taken into this chair, rubber apron, rubber hat and then they said, ‘Open up’ and I’m damned if I’m opening it. Oh, they were cruel, cruel. Then at the end they took off the rubber hat stuffed it into my mouth and I dived off the chair. There was a big wicker basket bed or settee. And I jumped on top of that on to this partition. And I sat up there like a cat and they had to go and get my Mother to take me away. They were cruel, cruel people.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

We had one or two friends who suffered and were in the sanatorium for months. Children of roughly my age, not too many. You got your injections for smallpox and diphtheria I remember that and then T.B. There was the injection when I was about twelve. They did the test and if it didn’t react then you got the T.B. injection in the senior school. The other thing that was the great scare at that time was polio and the Salk vaccine came in, in the middle to late ‘50s. That was the frightening disease at that particular time. My Mother was always very careful that we didn’t go and play in rivers and so on because that was felt to be a catalyst. Whether or not it was I’m not sure.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

I have no real recollection of the start of the NHS although from August 1962 I would spend the next 46 years working for it. I had been treated for measles at the house in Milngavie around 1942 but do not know how this was paid for.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

The state of medicine was primitive in those days. I’ll give you one example. My Grandfather had a heart attack at work and he walked home and I remember this, I remember seeing him coming home and today you would call the ambulance, you’d be on your way to, well we would call it the E.R. I know you don’t call it the E.R., but you’d be on your way to hospital, and eventually… in those days people didn’t have phones so you went to the call box and you called and eventually he was taken away in an ambulance.

In 1960 there was no real treatment for heart conditions and so the prescribed treatment was bed rest. So I remember visiting him in hospital and I was very close to my Grandfather in many ways and he died in hospital. And there was just no effective treatment. In today’s world it might have been different.

I took ill in primary school in 1955. I was 5 years old and developed really severe stomach pains and eventually they went to summon my Mother because we didn’t have a telephone. Nobody did. And we didn’t get a telephone until 1968 that’s how basic this was. Eventually she came and took me home and I was in bed and the pain just got worse and worse and eventually they called the doctor. Because in those days Doctors came to your house. By this time, I remember the pain just abruptly stopped which actually made me a medical emergency because I was now in peritonitis not appendicitis. The doctor showed up and took one look at the situation and told my Father to go call and ambulance and tell them it’s an emergency.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

My earliest memories of going along to the doctor’s surgery and hearing my Mother or my Father, whoever had taken me along, saying things that indicated this was new. It was so much better. And I remember you just trooped along to the doctor’s surgery, went into the waiting room and sat in a queue. There was no appointment system as such. You just waited there until it was your turn and the doctor saw you. It seemed to work.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

I had my tonsils out on the kitchen table in 1953 and the kitchen absolutely crammed with medics. An eminent Glasgow surgeon and my own G.P. and other people and a nurse. And I can remember sitting on the nurse’s knee and a wire, like a tea strainer thing put over here (covers her mouth and nose) and a bit of gauze over that. And something dripped which I think would be ether and I can remember the horrible stretching feeling as I passed out. And I can remember seeing the pulleys in the kitchen while it was all happening, because I saw green rails, they were painted green with a light travelling up and down them, and a lot of banging noises, and presumably that was the surgeon’s headlight. And the tools being chucked into a kidney dish and then someone carried me into the maid’s room which was just off…but what always struck me afterwards was having them taken out within distance of the range and the coal bunker. While my Mother paced up and down the corridor outside trying not to listen to the noises.

Christine McIntosh, born 1945, brought up Hyndland, Broomhill and Arran

I do remember discussions about the Health Service and how wonderful that was because my Grandfather had been a doctor and my Uncle was a doctor. And I can remember my Mother talking to me about what it was like to be a doctor’s daughter in the past and how different it was going to be with the Health Service. She would talk about how people couldn’t afford it and coming to her Father who was a doctor and sometimes he would take people for nothing and sometimes people would pay him with a chicken. And I was very close to my Grandmother and she was a very clever lady. She was one of the first female graduates of St. Andrews University in the days when women didn’t get a special award. She was political, so she talked a lot about the Health Service and what it was like to be a doctor’s wife in those days.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

The one thing I remember that strikes me immediately was a visit from your doctor used to cost five shillings and I do remember when that was stopped. Yes, that was a big thing that you didn’t have to pay for the doctor coming anymore. Yes, that’s the main thing in my thoughts on the National Health when they introduced free health. And that’s of course another great idea and that made a huge difference. Particularly to working class people who were never well paid anyway but five shillings, five shillings was a lot of money to have to pay out you know from whatever salary you got. At that time people would only be earning a couple of pounds a week, something like that. It wouldn’t have been much more. So five shillings out of that… you were reluctant to call a doctor in knowing that you were going to have to pay that. Although I suspect that a lot of doctors didn’t actually take it.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

Sulphur and treacle. I don’t know what that was for. We used to get big tubs of malt from the clinic along with the cod liver oil and the orange juice.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill