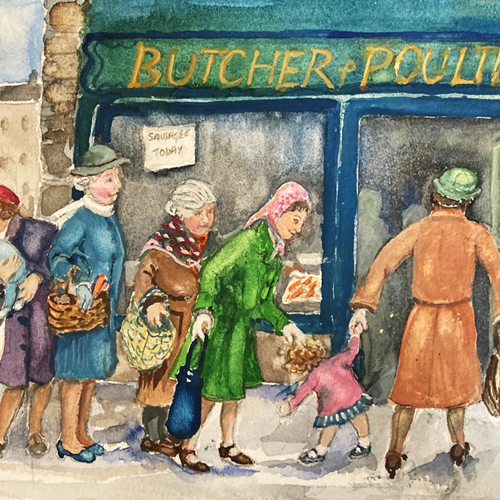

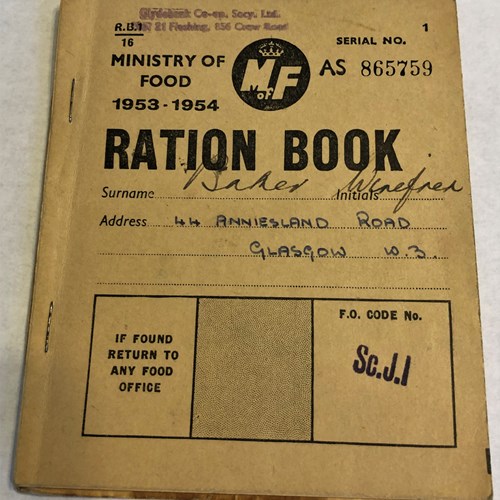

During the first eight months of 1939, life in Glasgow and the surrounding areas continued to be marred by the effects of the interwar ‘Great Depression’, which had lasted throughout much of the 1930s. Greater Glasgow had been one of the major British blackspots, experiencing high unemployment amongst working class men as heavy industry declined. Where industrial work was available, it was often dangerous and precarious in nature, and wages were poor, with the average male worker earning between £3.00 and £5.00 per week, whilst women earned much less. Whether in paid employment or not, most women still had labour intensive domestic and caring duties at home, and often took in ‘home work’, such as washing and mending, which was usually paid ‘cash in hand’ and not declared to the authorities. Officially, only one tenth of married women worked during this time, though the actual numbers of working women were undoubtedly far higher. Official numbers had increased during the interwar period as more middle-class women were working, at least until they married, in what were traditional male roles, such as clerical work, and in professions such as medicine and law.

Until 1948 there was no National Health Service (NHS) and little in the way of welfare payments. Under the National Insurance Act 1911, working men who earned under a certain amount, and who paid a small amount of National Insurance a week, were entitled to see a doctor and get treatment. Hospital and consultation visits were not included in the entitlement. Wives and dependents were not covered by this scheme. In Glasgow, the Area Corporation was in control of most of the hospitals, which provided healthcare to people with no other access to medical assistance. However, there was still a lack of beds for women and children. Infant mortality was high, 17-18 per cent higher than in England; diphtheria and childhood illnesses were all too common. A 1935 report by local health and nutrition pioneer Boyd Orr stated that most people in the Greater Glasgow region experienced levels of nutrition insufficient to keep the population in good health. Meanwhile, housing for much of the region’s population was often overcrowded and of such inferior quality that it had a negative impact on health and well-being. 10 Though they were still vulnerable to the diseases of the day, the middle and upper classes had access to more health care provision, mainly through the existence of subscription hospitals. They also had better housing at a time when buying a new semi-detached villa required proof of a steady wage, a £25.00 deposit, and a £1.00 repayment per week. And they could afford more nutritious food and could take advantage of the 1930s’ healthy eating fads.

Though they were still vulnerable to the diseases of the day, the middle and upper classes had access to more health care provision, mainly through the existence of subscription hospitals. They also had better housing at a time when buying a new semi-detached villa required proof of a steady wage, a £25.00 deposit, and a £1.00 repayment per week. And they could afford more nutritious food and could take advantage of the 1930s’ healthy eating fads.

In 1939, despite the ongoing health and housing issues, Glaswegians continued to enjoy some lighter aspects of life. Children and adults of all social classes enjoyed notable sporting events in the first few months of that year. Football carried on, as did athletics events and golf tournaments. Greater Glasgow’s many cinemas and dance halls remained open; attendees were mesmerised by new releases such as ‘The Wizard of Oz’, ‘Gone with the Wind’, and ‘Jesse James’, and they listened to the hits played by big bands and swing musicians, and danced to ballroom, jive, and jitterbug tunes. Escapism was then, as it is now, important to social and mental wellbeing.

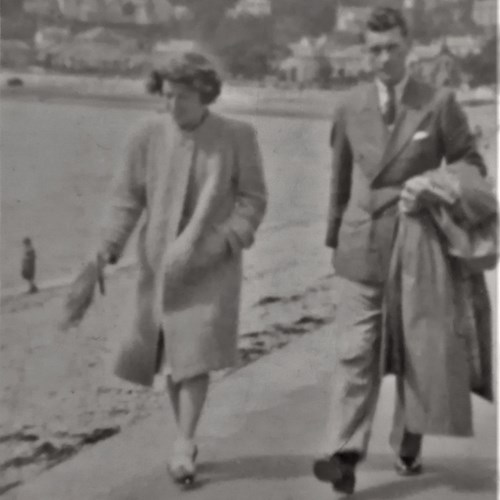

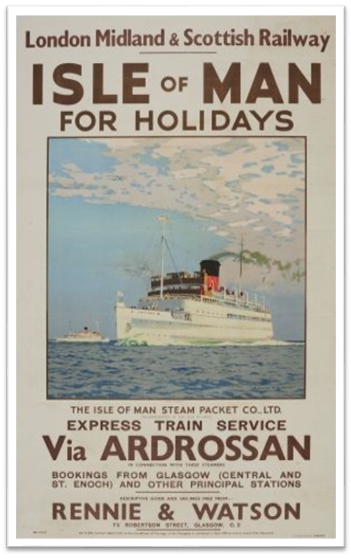

Holidays to the Clyde Coast and beyond, for those that could afford them, experienced a boom in the summer of 1939. The Holidays with Pay Act, 1938, may have been a factor in this. The financially better off went further afield to places such as Scarborough and the Isle of Man, which were more expensive to access, and accommodation was pricier. For example, a night at a B&B in Millport cost 20p per night, whereas it was 25p per night in Douglas on the Isle of Man

In May 1939, the shadow of impending war spread throughout Scotland. Families were required to register with schools to have their children evacuated if they had chosen that option. Older children may have been made aware of this by their parents and guardians. One can only wonder at the anguish experienced by the young people, and their families who had to make those decisions.

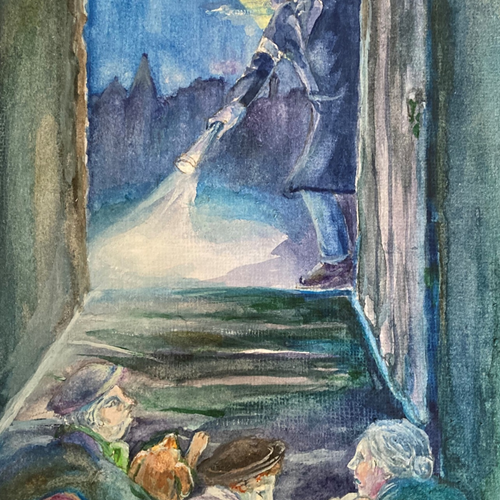

Trial blackouts were introduced in Glasgow in the July of 1939. At this time, ARP personnel were being recruited and trained – further tangible evidence that changes were afoot. Meanwhile, newsreels, newspapers and radio programmes reported events in Europe, such as the invasion of the then named Czechoslovakia, and then Poland.

Although a great deal of ‘normalcy’ remained throughout the 1930s and the first nine months of 1939, preparations for war were clearly evident. A lot was about to change for everyone across Scotland, including the lives of its children.

Childhood Memories

“Life before War”

Yes, I do remember that. Because oddly enough…because me and my family were evacuated

to relations in the country in County Glen outside Glasgow and we were there for three weeks and then the war broke out and we came back to our flat in Pollokshields. So we were never really evacuated there. I think it was a sort of panic move by my parents prior to the outbreak of the war and I remember the day the war broke out. I remember the adults crying and Chamberlain was on the radio. I remember that. I was seven.Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

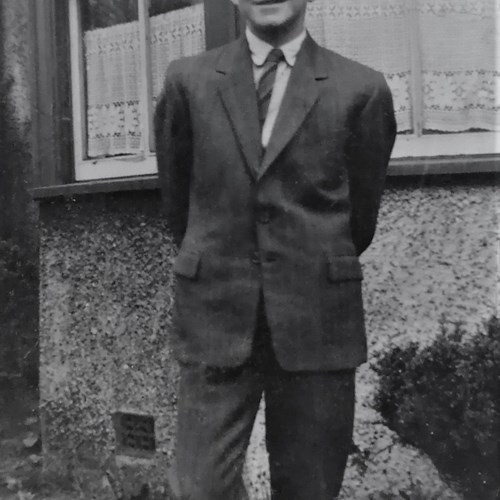

John Power, aged 20. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

In 1938 there was talk of war in Europe. Diplomats in many countries were involved in negotiations with Germany, in what turned out to be a hopeless quest to maintain peace. This did not mean a lot to an eleven-year old kid like me. There were more important things to occupy the attention of my family. Namely, the fact that with the arrival of my brother Michael in 1934 we were overcrowded in our one apartment flat. My mum took a look at the houses in Riddrie which were in various stages of completion. She thought that this was a good district; a kind of better type of working-class area. However, the house allocated to us was in Garngad and mum was not too pleased. This was a tough district. The new houses built here, three apartment, with scullery and bathroom, hot water in a copper storage tank from the living room coal fire, which also heated a range in the scullery, was a vast improvement on the one apartment in Saltmarket. These house, two storey tenements, were classified as “slum clearance” and my mum was not happy about the class of the neighbours she might get. This may sound snobbish but she was no snob. She was, however, concerned that we might get what is known today as “neighbours from hell”. We had not come from a slum and she therefore expected to be given a house in a district like Riddrie where, I suppose, the tenants were carefully selected. We ended up in 20 Provanmill Street, Garngad.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

The main memory was when we moved house. I remember the old fashioned range in the living room. And I can remember my Aunt giving me tuppence to go down to the shops to get some sweets. I do remember the air raid shelters being built and having long conversations with the men building the shelters, and marvelling at their tin mugs for tea. And thinking I’d like some of that tea they had.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

My earliest memories as a child I can remember us going across the road. I don’t know why I keep saying on our hands and knees. But that’s the way I seem to see it as opposed to walking or me being carried. We lived opposite a very large synagogue. South Portland Street synagogue which had a very large basement. And when there was air raids- a lot of people, if they chose, could go to the basement across the road. And I have memories of that.

I have some memories of living in the Gorbals, but I have extended memories because of the shop. At least once or twice a week from a very young age I had to go there to help out and I did all the dirty jobs, like when people wanted potatoes. In those days potatoes were delivered in sacks and in the winter half the sacks would be full of mud, so things like that. And ehm, being Jewish, in our shop, we also sold things like salt herrings and a product called schmaltz herrings. These were horrible, you had to get them out of a barrel.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

Well, I felt it was just quite normal, although poor, a poor area. It was a good area for roller skating because it had lovely smooth roads in the area that I lived in. So a five bob pair of skates out of Marks and Spencer’s that I got for my Christmas one year. I think that quite a few of us became very good roller skaters. In fact, I remember there used to be a hall, a dance hall in Partick, the F & F. And one night a week they used to have roller skating, just skating round the hall, so that was…and then football of course, played football in the street, yes, and hockey, we played hockey with tin cans out the midden. And a walking stick from an old guy that run a sale room and you could buy a walking stick for a penny. I’ve got all the bruises on my shin bone to this day. So yes, I felt it was a good area, a happy area. There was lots of pubs around the area. My Mum used to, that was one of her pastimes on a Friday night, leaning out the window with a cushion on the window ledge, leaning out there watching all the drunks getting thrown out the pub. So that was the area.

It was a lovely area to be brought up in as a wee boy, lots to do, lots of mischief. That was the area I was brought up in.

I think my favourite was going over on the ferry. I remember all the barrels outside the sheds waiting to be loaded on to the ships. And I used to walk over the barrels, you know, things like that. It wasn’t really mischief. It was a hive of activity, there was always something to take your interest. Then you had the steamers on the other side of the river. The pleasure steamers. You know, that took you to Rothesay, Dunoon, Gourock, Greenock. As I said, that was the area and I could walk into town from where I lived it was only a couple of miles.

Yes, oh yes. Not a lot. My Granny used to take me on the Campbeltown Steamers. She used to wake you up about five in the morning to go and join either the Dalriada or the Devar. And I think that’s what gave me the notion that I wanted to be a Sailor because I was at sea. I went and joined the Merchant Navy. I was in the Merchant Navy for eight years. So I think it was my Granny taking me on the Campbeltown boats.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park