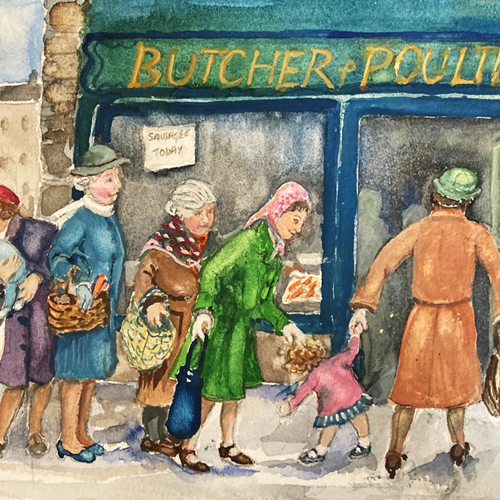

Rationing’, by Joyce Kelly, Artist in Residence, Communities Past & Futures Society

National registration of households began on the 29th of September 1939, twenty-six days after the start of Britain’s entry to WWII. This required people to register the numbers and ages of the people in their residence. Voluntary rationing was replaced by compulsory rationing in January 1940. This happened when Germany U-Boats bombed British ships carrying food and other imports in attempts to undermine the British resolve. At the start of the war, Britain imported 55 million tonnes of food, but that figure was soon reduced to only 12 million tonnes. The government introduced rationing measures in the hope that everyone would get their fair share of food and other items made scarce by the war. Clothes, furniture, petrol, coal, electricity, paper, and soap were also rationed and other materials were scarce. Many items continued to be rationed, or became rationed, years after hostilities had ceased.

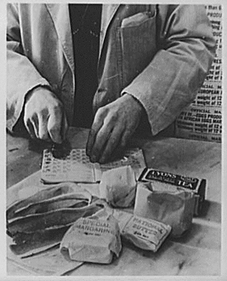

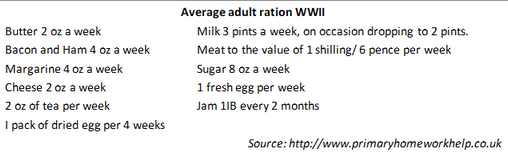

At the star, only a few types of food were rationed; these included bacon, butter and sugar. The number of foods rationed increased over time, and the quantities that were allowed per person fluctuated throughout the war. By March 1940, all meat was rationed. Tea and margarine were rationed by July of that year. In 1941, jam, cheese, and eggs were added to the list, as were rice, dried fruit, tinned tomatoes, tinned peas, sweets and biscuits in 1942. Fish was never rationed but was expensive, as boats were requisitioned for war work, and sea fishing became even more dangerous than usual. Potatoes and bread were not rationed during the war as they were regarded as important ‘bulking out’ foods. This also meant that fish and chips were never rationed, and the staple became a form of comfort food that was important for public morale. A wee fish supper was an important and much-loved treat for children.

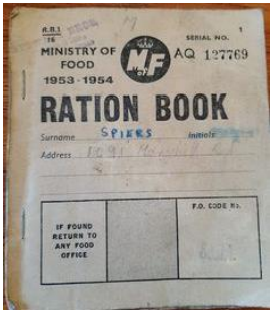

Along with an identity card, each person was issued with a ration book, which contained tokens for allotted items that had to be purchased with money. Most ration books for adults were buff in colour, though certain people and all children were entitled to different coloured ration books. Pregnant women, nursing mothers and children under five years of age received a green ration book, with entitlements to a choice of fruit, often dried or tinned (fresh domestic fruit such as apples were available in shops from time to time), a pint of milk per day, and double the supply of eggs that were issued to those people with the buff-coloured ration book. Children between the ages of five and sixteen were supplied with a blue ration book, and this meant that they could get fruit, the full meat ration, and half a pint of milk per day. The details of varying entitlements were stamped in the ration books.

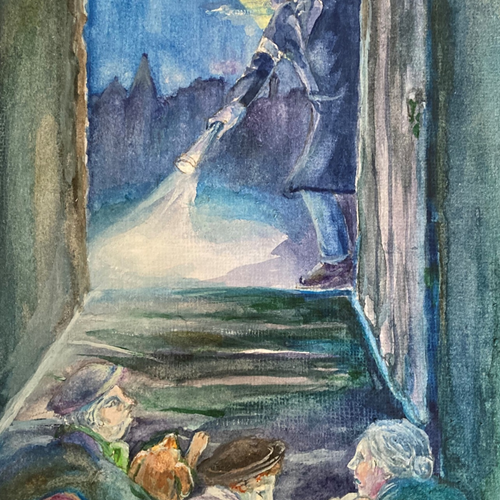

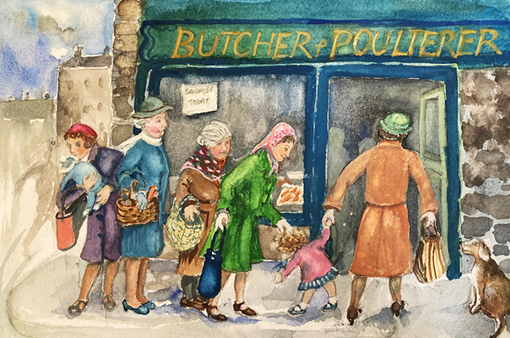

Each household would have to register with a food supplier for meat, vegetables, etc., and then stick with those suppliers. The ration book was put in a box on the counter and the shopkeeper would take the tokens or mark them as goods were purchased. There were invariably queues of people waiting to get into shops, and people rushed to them when they heard there had been a fresh delivery of food. One of our respondents, a child at that time, remembers that shopping was “really demanding work”. Mothers had to shop daily as there were no refrigerators at the time. Conversely, it has been said that some of the population received a more nutritional diet during the war than they had done beforehand, as rations contained a healthy balance of food stuffs. It is thought that most of the children brought up at this time benefited from eating a good diet of food.

Many people felt that food rationing was not as fair a system as the government had intended. As is human nature, some people had hoarded food when it became apparent that war might be inevitable. There was a lot of suspicion around hoarding and people were made to feel uneasy about this activity, particularly in towns and cities, yet people in the countryside often had access to extra supplies of eggs, dairy products and meat. Many children who were evacuated to the country benefited from this when staying in their temporary homes. Many families supplemented their rations in other ways. For instance, it was not unknown for some people to take advantage of the black-market, with goods, and, amongst many other things, oranges and bananas, finding their way to larders. A lot of families had someone who worked in a factory or other workplace and could eat in the work canteen; this saved on the household rations. Some schools also had canteens where children were fed. A number of people from Scottish cities caught trains and buses to rural areas, and there used emergency ration vouchers that were issued for people who were away from home to buy food in small towns and villages. In 1942, it was reported in the Fife Free Press that residents at a Fife holiday resort had become disgruntled with visitors coming in and buying up their supplies of food.

People overcame privations in other ways. Many inventive war-time recipes aped missing ingredients. Parsnips were used as mock bananas in dessert recipes, and carrots were used to sweeten things in place of sugar. Children often found that sweets were in short supply and replaced with cinnamon sticks, and sticks of liquorice root. American GIs often gave sweets and gum to children who lived near their bases, and “Any gum, Chum?” was a popular cry to those soldiers when in Scotland. Adults were also known to give up their sweet rations for children, with some kind souls handing them into shops or giving them to neighbours.

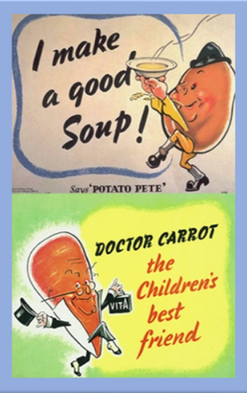

The Government started the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign in 1939, and every man and woman, who was able, was asked to grow food and, in some cases, look after animals. Every spare bit of land was put over to the cultivation of vegetables and the rearing of farm animals, and children were expected to help. They were also encouraged to eat their vegetables by poster campaigns featuring friendly characters such as ‘Doctor Carrot, The Children’s Friend’, and ‘Potato Pete’.

A quarter of the British population were entitled to wear some form of uniform. The manufacture of these and other military fabrics put pressure on the production of civilian clothing. Shoes were also in short supply in both civilian and army life, as rubber supplies were diverted for army use. Clothes rationing began on the 1st of June 1941, in an attempt to make the distribution of clothing fair. The number of coupons issued to most adults fluctuated throughout the war, going from 66 coupons a year at the start of clothes rationing, to its lowest level of twenty-four coupons per adult per year, in 1945. Eleven coupons bought a dress, two were required for a pair of stockings, and eight coupons got you a man's shirt or a pair of trousers. Women's shoes were five coupons, and men could be shod for seven coupons. It was a complex system and people were reminded by poster campaigns to plan out what they wanted to buy before going shopping. People of certain professions, such as diplomats and actors, were issued with extra coupons.

Children were given ten more coupons as of 1942, as they would quickly grow out of clothes and school uniforms also required coupons for their purchase. The Women’s Royal Voluntary Service set up clothes swaps to try and help this situation. This had been a usual habit for families on poor incomes, anyway, but it now became unfashionable, and even unpatriotic, to be seen in clothes that might be regarded as too new, or too showy. The ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign encouraged people to reuse and upcycle materials. Classes in how to make clothes sprung up nationwide. Not everyone was too keen on the thought of making dresses out of old curtains, but nonetheless this did happen.

Women’s clothes tended to be designed to be made with the minimum amount of material, hence the popularity of the pencil skirt during this era. Although clothes should not be seen to be ‘flashy’, women were encouraged to wear make-up and do their hair to boost their morale. Make-up was not rationed for this reason, but it was expensive. Women would improvise by using beetroot juice for lipstick, and boot polish for mascara, amongst other things. Friendships were formed with American GIs who often brought their female acquaintances the gift of nylon stockings.

Rationing was only gradually phased out after the war, and newly rationed items were introduced – items that had not been rationed during the war. This included rations on potatoes and bread, ostensibly introduced due to poor harvests, which proved to be controversial. Sweets were not derationed until 1953, which then caused a huge rush on the shops by children and adults alike. Rationing finally ended on 4th July 1954, when restrictions on buying bacon and other meat products were lifted. A great deal of WWII-era children carried their experiences of rationing with them throughout life, and were, and are, uncomfortable about wasting food and being unthrifty with their finances.

Childhood Memories

"Rationing & Making Do"

Sweets were rationed and I think. I remember I could get four lollipops a week. So my decisions were what days a week when there were seven days a week. What four days did you have your lollipop. So I think I worked out that usually it was Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. I had my lollipop and on a Wednesday. I spent my money on a comic. I do remember getting pocket-money when I was young that I was responsible for. You would get money for going to the cinema and that sort of thing. But I had an allowance every week, a small allowance something like sixpence or something. But that was for things like sweets and comics and presents, so you had to kind of budget how you were going to spend that, whether you were going to spend the sixpence in one week. Or whether you were going to save a few sixpences and have a couple of shillings to spend. So that money was mine and once it was gone, it was gone.

Marlene Barrie, born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

Yes, A green one (ration book), I think. The fruit…It’s just… I was remembering a wee while ago about vegetables and fruit and how you couldn’t get fruit. And the wee grocer, quite near us, would say to my mum if she was in during the day. “If you come tonight when it’s dark I’ll have some onions.” No fruit or anything but the onions were a great thing. To get some onions that was really good. And my friend whose brother was killed. He brought bananas back from somewhere. I remember getting a banana and I had never seen one before. I didna (laughs) really like it when I took the peel off it. But, no there was very little fruit and veg and we just had to…My mum was a good cook and she managed to make stuff that was healthy.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

We weren’t too badly off. We had a good grocer. And my Dad being in an office in a coal mine… sometimes the miners got parcels from the Government. I think they were either Canadian or American. There would be tinned meat, jam, tea, different things. And he occasionally came home with a box with goodies in which we opened, and barley sugar sweets that were quite a luxury at the time. My Mum gave me her sweet ration. She stopped taking sugar in her tea. She just took tea without milk or sugar. I was an only child so I suppose I was a bit spoiled. She made omelettes with dried egg. And occasionally we had a Canadian soldier, who was a friend of a relation of ours in Canada, and he would come and stay with us for a couple of nights. And he would bring something. He would bring sweets or chewing gum or something like that… It was a happy childhood really

We got our supply of coal because my Dad worked in the industry. Clothes rationing-I remember the coupons. And when my Aunt was being married, my Dad, I suppose on the black market bought clothing coupons from some of the miners, so that she could get extra coupons to buy her trousseau and her wedding stuff. I can remember doing that. I think my Mum was quite worried actually that he’d done that.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

I remember seeing my Mother’s ration book that would be about 1953. And I’m not sure if it was sweeties and butcher meat that was rationed. But I remember… I’m not sure if it was during the war or just after. My Auntie worked in Birrells in Glasgow and one of my Uncles took in some chocolates for the school teacher. Of course, sweeties was rationed, so she’s going ‘Where did you get them?’ and he said, ‘My Auntie works in Birrells’ and everybody in the class said- 'Oh you’re not supposed to have them.'

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

Well, you couldn’t get sweets but there was a sweet shop who used to sell like the broken bits of boiled sweets. I don’t know whether they broke them themselves or not but they used to sell them in screwed up balls of paper. And of course, word would get around that he’s selling his sweeties so you went and stood in the queue.

I can remember going to Rothesay on holiday. And there was a shop that made rock, but he only had certain times that he sold it. He must’ve made a batch and I can remember going to queue there. That was quite a novelty.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

Well, the main thing was, as I said, you couldn’t just walk into a shop and say I’ll have this that and the other. Whatever you had, you had to go in with your ration books. There were two ration books, one was for adults and one was for children. And in the ration books there were all these various coupons, for butter, for meat, for eggs, for sugar, margarine, all sorts. Clothes- if you wanted to buy a dress you might have to use five- or six-months’ worth of coupons. The coupons you got lasted a month. You got a whole book of them. And with sweets we’d go round the corner and ask Miss Grey about a week before the end of the month ‘Will you take next month’s sweetie coupons please?’ Invariably she said yes. Our sweetie rations would be used up very, very quickly. But there again the sweets that were on offer were very few. During rationing it was just so basic. There was no, erm, it’s very difficult to describe. You had your bread and some sort of butter or margarine to put on it. You might have jam if you were lucky. But for all that, I don’t really recall, it’s very difficult for me. In today’s world when we keep hearing the word poverty. Because from experience it was always poverty I was surrounded by. But we never ever used that word. We just accepted this is the way things are, there’s a war on. We’ve all got to do whatever we can.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in The Gorbals and then Shawlands

I remember parts of the early ‘40s with regard to ration books. And the things that were very hard to get. And it was at that time. I do recall my Mother went down to the social office there to get free orange juice for myself and my brother. We had milk powder, we had powdered eggs. We had all sorts of things which today we very much take for granted. But I didn’t realise how scarce all this sort of stuff was. I really wasn’t terribly aware of what was going on.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

Well, you were only allowed one egg a week for example and so many ounces of sugar. It was ounces, not pounds that you got. I just remember going to the Co-operative with my Mother’s ration book and she had the messages all written out. And I’d just hand it over and the grocer would make up all the messages. Tear the coupons out. Give you your ration book back and that was it. But my Father worked as a lorry driver for the railway, but he was stationed at Drumchapel Station. And I’m talking about Drumchapel before it was Drumchapel. It was only a village, and there was a station, Drumchapel Station. And there was Beattie’s Biscuit Factory two miles down the railway line. And my Father’s job was to take the raw material from the station yard to Beattie’s Biscuit Factory. And that was his job. And I remember he always had access to a bit extra sugar. There was always biscuits available. There was always a bit of coal from the railway yard available. And the Station Master was always supplied through my Dad. And the local policeman was always supplied through my Dad. So we always had wee bits of extras in that line you know. All these things were all rationed. Coal was not very available. That’s about all I can remember about rationing. I don’t remember being hungry. I don’t think we were very well fed because I was small. I was only five feet one and a half inches when I joined the Merchant Navy. And within six months I had grown four inches because I was getting fed. I got good feeding aboard the ship, good bread, plenty of it, plenty of butter and plenty of good food. And within four months I had grown four inches right up to the height I am now.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

I remember the wee book and the coupons. And when you used to go for Granny’s messages or that. You needed so many coupons. If you needed meat you’d go to the butcher and he’d take that wee bit out of the book. My Faither for some reason, he used to get extra. I don’t know where he got them from. I think it was maybe if he did a wee job for somebody. Nothing illegal. So we’d maybe have an extra couple of coupons.

Food-wise, we were lucky. Because my Granny and Granda up north they used to send us down rabbit, hare and chickens, things like that. So we were lucky in that way.

We had quite simple fare. We were never starving. I never knew what rationing was to be honest. Because you experienced it. it’s not as if it was going from having stuff to a lack of stuff. I didn’t have it in the first place. So growing up it was just part of your life.

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

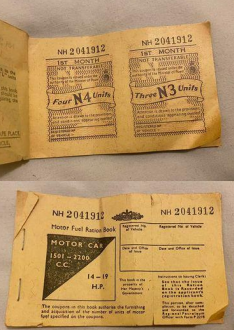

Petrol ration book belonging to James’ 84- year-old father. Courtesy of James McGlone, ‘Lost Glasgow’, FB

I’ve got my ration book here which for some reason my Mother kept. And it’s got my name on it, and also an identification card. She was good at keeping these kind of things. When I opened up the ration book, I found this - that’s your Co-op slip. When you went to the shops and you bought something, they wrote it in a book and they gave you a carbon copy of it. I used to be fascinated by this carbon paper, it was fantastic, before you had photocopiers.

I remember sweeties being rationed. There was a thing as well if you saved up your sugar and took it to a shop like Birrells or R.S. McColl’s, they would give you sweets. You would give them your sugar and they would use it in their factories, I suppose. One memory of that; I must’ve been about nine or ten by this time, my Mother would take some sugar to her Mother, and I came in from school at lunchtime and I saw the sugar in a brown bag, and I got my finger and just stuck it right in the sugar bag to take a lick of the sugar. And I didn’t realise she’d put an egg in there to transport it to give her Mother, this egg, and my finger went right through it. It ruined the whole lot of the stuff.

So that’s what it was like, you gave people presents of wee bits of sugar and stuff like that.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemillk

I have all my ration books right here. My favourite page was the sweetie one and there’s still some in here so I didn’t get using them all. D was for two ounces and E was for four ounces. Now fast forwarding a bit when everything went off rationing. There was so many people clamouring to get the sweets. They had to put it back on rationing again for a short time. So, it was a disappointment for everyone for a short time. In Fintry we only had one store. A little store that sold everything. And she was very careful that you only came once that day, or whatever, to get them and not get too many. Because so many people wanted the sweets.

We went up to the farm with a bucket to get milk and other kids went with us too. I used to swing the bucket. So there wasn’t very much milk in the bucket when I got home.

My brother would actually be able to send some food home to us sometimes. The one thing being was a big can of lard because then we got our chips.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I remember the ration books and how for example… well we obviously had one for everybody in the family. And my parents well, my mother, she would do the shopping and have to go to the grocers, for example. And they would cut out the coupons for whatever rations were being bought. And then there was the sweetie coupons as well. And around the corner from us there was a wee, I’ll call it a newsagents, but they sold everything. And that’s where we would go to get sweets. I know the ration books lasted until about 1953 I think. They went on quite a bit. And when we’d moved up to Pollok you’d get ice cream vans coming round because there was next to nothing in the way of shops. And the ice cream van had to take the coupons as well.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

I remember the ration books. And when you went to get anything at all, they tore a wee bit out of it for what you were due. And they had sweet rationing then, but you could go down with your coupon or pennies, or whatever it was at the time, and get some sweets, which was great. And also, I remember the coal was rationed. The coalman used to put his big heavy bag of coal on his back and bring it up. We were one stair up. And he used to bring his coal up and put it in the bunker in the house. And the clothes of course. I didn’t have a lot of clothes bought because I fell heir to my sister’s clothes, although she was five years older than me. So, they tended to be too big and had to be tucked up, or hems taken up. But I don’t remember getting new clothes as such.

She was very good. She was on her own. She was a butcher, my Mother. So we didn’t have any problems as far as I’m aware of having meat, a chicken or a fowl as she called it. She used to bring them home and she had to pluck the feathers and then seal it with the red-hot poker.

So the fact that she was a butcheress and worked just down the road. It meant too that she was out all day from six in the morning until teatime at night. And my Aunt cared for us.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up in Govanhill and Southside

M. McKinnon in her ballet dancing days

Oh yes, I can’t remember the amount, but it was ‘the big week’ and ‘the wee week’. I think this was for butter and if you had children at a certain age maybe you got an egg or something like that you know. But most of it was powdered egg. You had your ration books for the shop. That was till well after the war because when we went to Pollok in 1948. I’m sure we still had ration books then.

I always remember them making soup, there was always beautiful soup and full of vegetables. You always hoped you’d get an outsider with it, you know. The bread was still wrapped whole and had to be sliced up. With your Mummy trying to spin it out, and still hoping you got an outsider with your soup. It was brilliant.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

I can remember we didn’t get a lot of sweets. We didn’t get a lot of things that are commonplace nowadays. I know that I never liked eggs when I was younger because my Mother told me I had been fed dried egg when I was very young, and I didnae like it so after that eggs were a no-no. I love them now right enough but I went through a phase and blamed it on the rationing.” “I think it was more obvious at Christmas time. In those days you got an orange in a stocking and even a bar of chocolate was a luxury.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

I was lucky. I had a great Uncle who was a confectioner in Aberdeen. And we used to get off cut dolly mixtures and so on. Occasionally, and there was also, I think I remember, the meat rationing. We lived in Aberdeen and fish was relatively easy to come by so we weren’t starved. I do recall my grandmother when I was about four or five allowed me to play with a shop and gave me stock of raisins and various other things. And after an hour or so she came back and I said the shop was shut because the stock had all gone. But obviously I had used up a bit of the rationing that was due to last for a month or so.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

I certainly remember that. And the day that word got round that they had bananas in the shops. Bananas-and people were rushing out their homes to the greengrocers to get bananas. An even stronger memory of rationing was in Greenock Central Railway Station there was the vending machines for chocolate. And of course, they were empty and we would stand looking at these machines you know like as if we were watching the telly. Just watching where this chocolate should be. But nothing in it and the imagination of just being able to put a coin in there and get a chocolate bar was just too much. I certainly remember the rationing, although I don’t ever remember being hungry. So it must’ve worked out quite good; that there was sufficient for people to eat. Providing they had the money of course. But people did exchange the coupons of course.

When we lived in Greenock. We lived opposite the Westburn Sugar Refinery. And there was always sugar, you know, available. Off the ration because the factory was across the street. So, my parents use to make sweets They’d make candy and tablet and all these kind of things.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

Grandmother's ration book 1953-1954. Courtesy of Valery Willis, ‘Lost Glasgow’, FB

In my family, we all had our own separate little bits of butter. And when we finished it, there were no more bits of butter. I remember all those domestic kind of things. I don’t remember probably until the end of the war really thinking too much about the war. I was a happy little girl.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

Again, we also had coupons for clothes and lots of clever people searched their wardrobes for clothes to be recycled. My Aunt Kath got married in 1944 (just before mum went into hospital) - her husband was in the R.A.F. (not a pilot but something to do with security) and as, the war was drawing to an end, he unexpectedly got 2 weeks leave from his post in Cairo, so a wedding was hastily arranged. Mum managed to get me a dress from a second-hand shop, hurriedly knitted me a bolero with wool from a ripped down jumper but shoes absolutely stumped her. Nothing fancy in the shops only what they called 'utility' so there I am in the wedding photos in my wedding ensemble wearing brown lace-up shoes! I also have a paper doily with artificial flowers sewn on as my headdress. Luckily, Kathleen secured the loan of a wedding dress that was circulating amongst prospective brides. That was the norm then. (I understand that our Queen, then Princess Elizabeth, had to save her clothing coupons for her wedding dress).

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

Obviously rationing went on for quite some time after the war into the early ‘50s I think. But what I mostly remember having been a small child was ‘the big week and the wee week’ for butter. So, you’d have miserable bits of butter and then it would end up being margarine or dripping on your toast for the end of the week. Because there wasn’t enough. Whereas the big week was more exciting. And I remember also we used to go to Arran for eight weeks holiday in the summer because my parents were in education. And we had to save up our sweets to go there because you couldn’t get sweets on the ration in Brodick. Because that’s not where we were registered. So, we used to save them up and put them in a great big tin. All these boiled sweets to take away, that we could take out walks and satisfy our needs for sweeties. So that’s really what I remember about rationing.

Christine McIntosh, born 1945, brought up in Hyndland, Broomhill, and Arran

I remember the rationing. My Dad one day buttered his bread on all sides before we realised he had used all the butter. He laughed and said that was how we used to eat butter. I remember too he used to boil an egg and cut the top off for me and then he had the rest that was at one time when I lived with my Dad for a short time. The only sweets I remember were when some American soldiers stopped by they always brought lots of sweets. One awful memory I have was when I lived with some strangers to me but obviously friends of my Mum, the adults all sat around the table after dinner and cut up old cigarette ends and made that tobacco into new cigarettes. I decided I would never smoke and I never have.

There was a rhyme at the time. Where was Moses when the light went out? Under the bed looking for a doubt. A doubt was a cigarette end.

Another memory was the way we found paper and pencils so scarce. My Dad was a very good drawer, and our amusement was to draw-often. I would say we drew daily. To this day, I treasure paper and pencils. At school we had to hand in the ned of an old pencil before you got a new one. By ned, it meant it was a stub a little larger than the one you handed in, A brand new pencil is a treasured thing still. We are so lucky.

Matilda Jane Holmes, born 1937, brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh, and other places

My Mother, she had a ration book, ration cards and within the ration book there was a section if I recollect it was in the back of the book, for sweeties. So, we were given these sweetie rations and we would go down to Nancy’s. Nancy was the last shop in Gibson Street before the bridge on the left-hand side. There was a sweetie shop. It was absolutely phenomenal, and you would go for different types of sweeties and of course the equivalent of rations there were stamps. It must’ve been an awful carry-on, adding up all the different stamps of different value. But I do know that I went off boilings as a result of all that. They were too hot for me. I loved Smarties.

Nancy worked there with her sister, and they were Stafford Hamilton’s aunties. And Stafford lived at 99 Otago Street. He was one of my closest friends and his father had been a spitfire pilot during the war. But his real job was as a Grocer. And eventually they moved to down Wishaw way, and it broke my heart because I’d lost my best pal.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow, and Comrie

Peter McNaughton, the younger boy, with his dad David Baird McNaughton and brother David, in Comrie, in 1950

Well we didn’t have a garden because we lived in a flat. But one of the things I do remember is what we called the pig bin across the road on the pavement where we always put the leftover food. And it wasn’t very nice because there was a lot of rats. I remember that and my Mother saying, ‘you take the stuff to the pig bin’. And not wanting to do it because even though it was just across the road. I was worried about the rats.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

Yes indeed. We had an allotment in Broomhill and we shared that with my Aunts. And I know that we got vegetables and things like that from the allotment. And I presume we also helped in cultivating it. But then again that wasn’t something I did. One of my Aunts was green thumbed and she was the one who did most of the cultivation. But I remember the allotment.

Until you mentioned it, I’d forgotten about it being a feature of the actual war. My Aunts told me all kinds of stories. They were in the A.R.P. in the Air Raid; they were Wardens and they had what they used to call ‘high jinks’ when they’d be out waiting looking for incoming bombing planes. Again, these were stories I heard from my Aunts rather than my memories of the actual planes themselves.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

I remember sweets being rationed and the rationing, I think being briefly lifted and quickly re-imposed. When it was finally ended, I was sent to queue for a box of Cadbury’s roses. My mother made sweets occasionally during the war. I was also sent often from 1944 on to queue for available butcher meat which was rationed. I know we got coal and soap during the War but I don’t know if rationing affected our family. I did not know clothes were rationed. I never saw a GI.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

No, there was no allotments near us but we did have a back and front garden. And I don’t know if this is relevant or not. But the golf course gave over two of their holes to farmers. And they had corn. They grew corn and I remember helping with the harvest thinking this was great fun. You know building the haystacks and running around on the horse and cart. No there wasn’t anything. But we had a neighbour who grew all his own vegetables and supplied most of us on the street, you know, with vegetables that he had.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

Once a week we would take our coupons and get our sweeties for the week so that was always a big treat. Just about everything was rationed. I remember one time, I was about fourteen and because there was five of us we got a little more rationing than my Aunt who lived alone. I remember going up to Glasgow. I went by myself to give her some of our rations to help her.

My Mother, she was a seamstress and she made a lot of our clothes. And when I think back. We were dressed beautifully because she was always sewing and we were like her little dolls. I remember she had like a cousin-in-law and she used to get things from the black market. So she told my Mother about it. And my Mother invested in some of this material. And one time there was a rumour that a lady was to find out who was getting this material and I remember my Mother having to throw it all in the fire, she was so afraid she would be caught. I’m sure she got more after that. I don’t remember the lady coming. My Mother had two Aunts. And when they were finished with a dress, she would take it, cut it all up and make dresses for us. I had a white dress and it was from a pair of white linen pants from my Father. And she cut them up and made me this white dress and she ran short of a little bit and she put a blue bib on it, sewed in. I remember that dress well.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

I remember I was sent across the road. And I was sent a message over to the fruit shop because they had heard that the bananas were in and there was a queue. So I was sent over to stand in the queue and wait for our quota in bananas. I don’t even know how many we got and that was the end of rationing. Then you were free to buy anything you liked if you had the money. But not a lot of folk had money by that time.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

I think the main thing was sweets taken off the rationing, that was later on that was much later on, and there was a queue outside the shop and down the road. I remember my Mum and Dad in Port Rush and we travelled over the border to Eire. And I remember going into a sweet shop and being absolutely gob-smacked at the jars of sweets and chocolate and I said ‘Can I have this and can I have that’ and my Mum saying ‘You can have anything you want’. I couldn’t imagine, I couldn’t believe that we didn’t need coupons for these. I think that would be about 1946.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shott

In Fintry we had rose hip trees and I’m guessing they were wanting rose hips. So I would get them and take them in. I think you got some money for them, like a penny or something. That was to make rose hip syrup for vitamin C. They had plenty of that, plenty of rose hips.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I remember rationing stopping. I can remember the first time I had yoghurt, I can remember thinking I don’t really like the flavouring in it, for a long time, because it was exotic. And we didn’t even have a fridge until I was at secondary school. We got one when we moved into the new house and it was still there when my Mother died. And she was 93 when she died. It was in the house when we emptied the house. It was the same fridge all our lives.

Christine McIntosh, born 1945, brought up Hyndland, Broomhill and Arran

It was really post-war VE Day and then playing in the streets and all the issues that were associated with the war and shortages and all of the rationing and all the various events that we all experienced coming out of the war. Having the first banana. Being taken up to the shop having only seen a banana in a book before. And my Mother took me up to the shop and then showed me a real banana. And I tasted my first banana probably age six or something like that. I just have a memory of the actual novelty of having something that, that it was exotic, it felt quite exotic. And then the day the rationing of sweets ended and you were able to go into the sweetie shop without restrictions, I can remember that.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and FintrY

Elma Robertson beside her parents and younger sister during WWII

I do remember food was rationed. I do remember the sweets being rationed. My Grandfather gave us his coupons but the shops…very rarely did they have sweets in. We lived opposite a newsagents and we’d see from our window the sweets being delivered but we didn’t get our newspaper and things in that shop. So we’d go over with our coupons and our money. But we would be told they had none and if you saw sweets anywhere you were lucky. Right up until about 1950 the sweets were still on ration.

I remember we went to Paris in 1951 with the school. And we were quite delighted when we got on the boat at Southampton because you could buy chocolates without coupons.

We had no bath. We had a toilet that we shared with the people across the landing from us. So at the weekends, I used to go up to my Gran’s for a bath. And I would have to take my breakfast with me because nobody had any spare food. And I was getting my ration of bacon and egg to take up to have. Because it was one egg per book and things were scarce. I think it was about 1945 before I saw a banana. My Gran managed to get some bananas.

We were lucky my Mother’s two sisters went to America and her oldest brother was in Bermuda. So we used to get parcels from America during the war. It was great excitement getting a parcel that came from America because there would always be some sweets for us and different cake mixes and things that you couldn’t get here. So we were lucky in that respect. One of my Aunts worked in a butcher so you couldn’t get extra butcher-meat but you got a couple of slices of corned beef or things like that. My Uncle the gamekeeper, he used to get us the odd rabbit. And his brother was a gamekeeper in the Isle of Mull. So sometimes we got venison. We weren’t so fond of it, but my Father liked venison.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick