During the Second World War, Glasgow was identified by the Nazis as a strategic target mostly due to the fact it was a hub of industry and was supplying the allies with ships and ammunition during the war. Clydeside was an area of particular interest to the Germans, Clydebank specifically, as it was the home of John Brown Shipyards, which manufactured anti-aircraft fire and medium calibre guns, and other factories such as the Singer Corporation Factory, which built weapons for the government. On March 13th 1941, Clydebank came under attack and was devastated by a two-night aerial blitzkrieg campaign, which left 528 people dead and a further 617 people injured. During the two nights of constant bombing, more than 1,000 bombs were dropped on houses and tenements, leaving only seven out of 12,000 undamaged, and led to more than 35,000 people being left homeless. Isa McKenzie was 12 years old at the time of the Blitz; she described how her father got her and her brother dressed in their best coats, and took them to a room and kitchen flat on the bottom floor of her tenement. She remembers a lady standing by the front door who would shout “Duck” whenever she heard a bomb, and having to leave the building after five hours of sheltering as it was on fire. Isa and her family made it to safety and spent the night in a local billiard room, only to emerge the next morning to find that they were homeless, as their building had been completely destroyed.

It has been argued that Clydebank was more underprepared for the blitzkrieg attack than it should have been, considering it was a densely populated town with over 55,000 inhabitants and high-value munitions factories. Historian Les Taylor stated that the reason so many people were killed in the raid was down to a ‘creep back’, which meant that the Germans were forced to release their bombs early over Glasgow to avoid the gun fire. Despite the Clydebank Blitz being the worst case of destruction and civilian death in Scotland during the war, it was considered a failure by the Germans as only one person was killed for every two tonnes of explosives dropped, a mere 1% of the military’s pre-war planning. However, Glasgow was not the only place in Scotland to suffer at the hands of the Germans. The Luftwaffe also bombed Greenock on the West Coast of Scotland in 1941, in a two-night blitz that started on the 6th May, and left 271 people dead and 10,200 injured. There were reports of an air ministry decoy being used on the second night of the bombing, which consisted of mounds of combustible materials being lit over a wide part of woodland to appear as a burning urban area from the sky. This decoy was successful and resulted in the shipyards, which would have been the intended target, emerging relatively unscathed; however, other factories, distilleries and the sugar refinery were badly damaged. In Greenock, like Clydebank, it was civilians who took the brunt of the attack; however, the decision to flee to tunnels in the east end of the town on the second night undoubtedly saved many lives.

Both the Clydebank and Greenock Blitz were widely documented; however, it can be argued that their infamy, along with wartime censorship, meant that smaller attacks were not reported and when they were, they were vague. Despite the devastation caused in both Glasgow and Greenock, it was Peterhead that was the most bombed location after London. It was bombed 28 times and although it was of no strategic value, it was the first place the planes saw when attacking en route from Norway. There were also a number of other smaller attacks in places such as Campbeltown, Fraserburgh, and Montrose, which were bombed more than a dozen times and, although they were not widely reported, they were an important part of the story.

Govan also came under attack from the Germans, and one man who experienced it made it his vocation to talk and write about the untold stories of the people of Govan. George Rountree describes how he believed he had spotted a German reconnaissance plane taking aerial photographs whilst playing with his friend in the street. He wanted to tell his story as he felt that the least-famous air strikes were being left out of historical accounts. On 13th March 1941, George found himself sheltering in his aunt’s house alongside his mum and sister after the siren alerted them to an imminent attack. He recalls how the house was filled with twenty to thirty people, and the way the building shook from the explosions and gunfire. A parachute mine landed 400 yards from where he was sheltering, filling the room with a thick haze. George spoke of the devastation he witnessed when he emerged the next morning, the piles of rubble that were still burning, and the civil defence working frantically to determine if anyone was buried underneath it. Two buildings in the street had been completely destroyed overnight, leaving sixty-nine residents dead. However, that was not the only attack that took place that night and, by morning, news had started to filter through that other areas of Glasgow had been hit. In Scotstoun, a mine blew up between two shelters on Earl Street and Dumbarton Road, killing 66 people; meanwhile over in Partick, bombs fell on Peel Street, Hayburn Street, and Crow Road, killing fifty. Hyndland also took a direct hit that night, as a parachute mine hit Dudley Drive, destroying three tenements and killing 36 people.

These and many other tragic incidents that took place during WWII have largely been forgotten, but not by the children who bore witness.

Childhood Memories

“The Blitz”

We didn’t go anywhere, we stayed in the house. But I do remember the planes going over to Clydebank. Sitting on the back steps with my Mum and Dad. Seeing the planes going over, seeing the flashes. And my Mum saying ‘If we’re going to die, we’ll all die together’. I didn’t fully understand that. I thought it was just a big adventure. I don’t remember being scared.

The Blitz started, it was my 6th birthday on the 14th of March. It was on the 13th and 14th of March. We were eagerly awaiting my Aunt arriving the next day. She was bringing a birthday cake for me and she had been involved, of course, in the Blitz. And my Mum saying, ‘Oh you’re as white as a sheet’. That’s what I remember about the Clydebank Blitz.

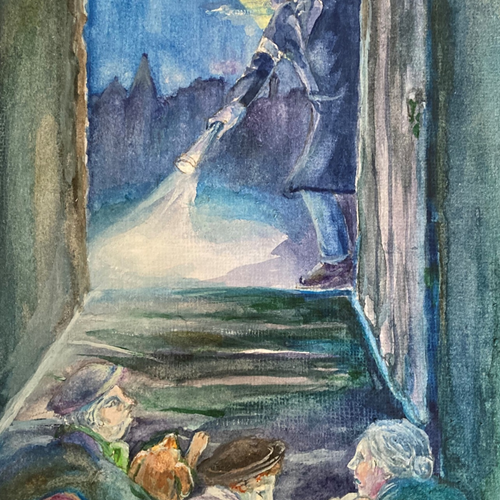

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

I don’t remember anything until I got bombed out. I can’t remember the actual date it took place. But I was staying with my Granny at that time in West Street. And as I said she was only two and a half blocks from the River Clyde. And I can remember the siren going at 9 o’clock at night and my Granny saying, ‘Come on, time for your bed’. And I remember going to bed and the next thing I knew was the ceiling had caved in on top of me. And a policeman had come up to get me. And my Granny had a lodger. And first of all, I got up before the policeman actually came. And Wardie’s Stables were at the side. I can remember it vividly to this day, Wardie’s Stables were on fire and the men were in to get the horses out. And they were running up the street with two horses. Where they were going I don’t know and my Granny’s floor was littered with glass, broken glass. And her lodger, old John Lucas shouting down ‘Where are ye?’(he was blind), and ‘Where are ye Mrs Burns?’ I says, ‘John, go to bed and I’ll go and get my Granny. And just then the policeman came in the door but half the stairway was blown away. So he got me down into the close to where my Granny was and then my Granny saying to me ‘Go and get your Daddy”. So I had to run through the streets to get my Mum, well to get my Father to come and help out.

Then at that time, the two churches that were at the back of us at Patterton Street and Nelson Street, they were on fire. One of them was flattened and the other was set on fire with an incendiary bomb and right down Nelson Street/Ballater Street to Morrison Street. That was all bombed all the way down. The steamie was flattened, I can remember that.

So that was the worst night I can remember that we had. That was the worst night that I experienced during the war.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

When my husband lived in Kelvinside, they had a bomb land there and it demolished some houses.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I can remember the day when I was four and we moved to Tantallon Road and that in itself was a little tale. What had happened was I think sooner or later my parents wanted to get us out of the Gorbals, there were six of us all together - myself, the youngest, my brother Gerald, my brother Hymie and the eldest was Ellis, and I think we got out sooner than expected. My Dad had an Aunt in Tantallon Road, Shawlands and in 1941, following a raid at Clydebank they reckon a plane, a German plane on its way home, to lighten the load, to get rid of its bomb load, and a bomb fell a direct hit on a tenement in James Gray Street which is just up the road from Tantallon Road. My Dad’s Aunt, Mrs Freedman, she panicked, and wanted out of Glasgow quickly and sold the house to my Mum and Dad.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

We had an air raid shelter at the bottom of the garden. I do recall seeing barrage balloons in the air which I had likened to elephants, big grey elephants in the air. And of course, being adjacent to Portsmouth they were to protect the shipping that were docked in Portsmouth dockyard at the time. Because the Luftwaffe went across on its way to London. And also, Portsmouth suffered quite badly from bombing, as did Gosport. In fact, a few houses down the road were hit by an incendiary bomb and as far as I know a family were killed.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

When we were walking home from the cinema, I remember seeing the pill-boxes along the edge of the River Clyde. And the search lights looking for enemy aircraft in the sky.

There were fuel tanks up at the back of Old Kilpatrick and two or three of them were on fire but they managed to put it out.

We used to collect things. It was like long bits of silver paper that planes would drop. This was something to do with the radar. It deflected the radar.

I remember in near the school football pitch there was a big barrage balloon for quite a bit of the war. That again was something to do with the radar or something like that. But this huge great balloon was in the field next to the school.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old

I remember the first night of the Blitz we were at a Shirley Temple film. My Mother and a neighbour and I. And just halfway through the film the lights went on in the cinema and the manager went up on to the stage and announced that enemy aircraft had been sighted and if we wanted, we could spend the night in the cinema. Or if we wanted to go home, we better start making our way home. So we went home and we couldn’t go into our air raid shelter that night because my Father had a car engine in it, it seemed. And what I remember of the Blitz was being in a neighbour’s house which was the bottom floor of a small tenement. I just remember all the big legs round about me because all the neighbours were in. But the next night of the Blitz my Father had emptied the shelter and we were in the shelter from then on. Anytime there was an air-raid my Grandmother came down luckily for her…and my young Aunts came and my Uncle because their house was bombed that night, it was flattened. As were quite a few people in Old Kilpatrick. They’d lost their houses and their possessions.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick

“Although I don’t remember, I vividly remember my Mother’s stories. Because she sat through them in the top flat in Hyndland that I was brought up in. And she told how they used to sit in a lobby press a lot of the time. This was in a top flat but they sat there because there were no windows in the hall. And she used to sit eating Rennie’s because she used to get terrible indigestion every time there was an air raid, and did old crosswords from the old papers that were stacked up in the cupboard for lighting fires and other things. So she used to sit doing the crosswords. This was before my Father went to the desert because he was slightly old for the first call up. So the war was several years in before he joined the RAF. Also, my Father would tell me, people who lived in the ground floor flat…all the rest of the tenement used to go and gather in the ground floor lobby press. And he used to say, ‘there’s no point in sitting there, our piano will land on top of you’. So that was quite an amusing sort of story.

There was also the story of the woman that took her windows out in buckets to the tip the day after an air raid she said she had a diamond studded piano because all the glass had impacted the front of her piano. And it looked as if it was all covered in diamonds. So, that made a big impression on me as a child. That was from a land mine that fell on Polwarth Gardens as it was called in those days, in the middle of the tenements there. And because of which the flat across the landing from hers had sloping floors. Because the blast had sucked the walls out and they’d popped back in again. So I always knew that Mrs McMillan had slopey floors.

My parents used to tell a story of how in the early days of the war, my parents they were caught out by falling shrapnel because an air raid hadn’t ended. It was a beautiful evening and they’d gone out for a walk up to Hyndland Road. And they ran down Novar Drive holding hands and laughing like lunatics. Which always struck me as very youthful and bold of them. And I know my Mother was evacuated from Glasgow. She was teaching at that time. Because married women had to stop teaching when they got married. They couldn’t teach anymore. But once the war started they were all asked to go back again and she was evacuated with her pupils to a farm in Dumfriesshire. And she remembered the farmer reading the paper at night and saying, ‘Someone’s died in Glasgow, do you know them?’ which was quite funny. Then my Father joined the RAF. He was too old at the start of the war but he signed up rather than being told to go into the H.L.I. Because he didn’t like the idea of that.

So that’s as far as I know about the war, the things I remember my parents telling me.

Christine McIntosh, born 1945, brought up Hyndland, Broomhill and Arran

There was a German plane came down a few miles from Shotts. And I think it was rescued and sorted up a bit and they brought it to Shotts. Probably in other places as well. But it stood outside the local fire station for a week and they had a step ladder you could go up into the cockpit. I didn’t go because I thought the German pilot would still be in there. And I was scared. But I remember going to see it.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

I remember, as I say- I would’ve been about four years old and I was standing in the entrance of the close. We lived in a tenement building and ehm, of course it was the baffle wall outside we’ve already spoke about and also there was a tarpaulin sheet that came down the front to keep the light in. Anyway, the adults must’ve been pulling this sheet aside and watching the planes that were flying over the top and I heard one of them remark that the planes were dropping flares which would account for the brightness. But of course, to me a ‘flair’ was what you walked on in the kitchen. And my imagination was trying to imagine why planes would be dropping these wooden objects covered in lino on top of us. It was years later before the penny dropped and I realised it was flares not flairs.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

I remember there was a big café but it was bombed. A big Italian-type café. It was bombed in 1941. Most of my memories are round about 1940.

My Grandmother had a chip shop in the village and I remember being around the chip shop. And it was closed at the beginning of the war because of rationing. And then later on in ‘41 it was bombed. Luckily, my Granny didn’t have it by that time.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick

My memories of air raids proper was the terrible sounds of the sirens. When the siren would come on because you did not know what to expect, being in Shawlands we were quite some distance from Clydebank where most of the bombing would take place, the Clyde obviously. But knowing that Shawlands had been bombed and that’s just because the bloke wanted to lighten his load. It was always lovely to hear the All Clear. It was a siren, but it was different.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

There was one family, the Rocks, that was the name of the family. I think they lost something like seventeen of their family. It was the biggest loss of life in Britain for one family from the Blitz. They had all went to their Granny’s. I think there was only two survivors. One was on night shift and the young girl who survived she’d be roughly the same age as me. I don’t know how she survived. She must’ve been away staying with neighbours or something.

There was an awful lot of deaths. And the ones that were in my class at school, I know that some of them lost family members.

What I do remember, one man, a man called David something and when I started working in John Browns. I would’ve been about 16 at the time. He was a journeyman electrician and he was a lovely guy but he couldn’t speak properly. He was deaf, but you could make out what he was saying. And his hair was virtually pure white. Somebody told me, I didn’t know, that David had been buried under the rubble for three days. That’s how he lost his hearing. They dug him out after about three days.”

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

“Up in the hills in Dumbarton they built a fake town. We lived right on the Clyde also. And the Germans flying over thought it was a town. And they really bombed it hard and when we got the clearance to come out of the shelter, my neighbour, not the older woman, she took me up in her arms. And pointed to all the fires at the back. And she said it was fairyland. I remember that vividly. And I thought it was lovely not knowing what it was.

We had an incendiary bomb stuck on our roof. I don’t remember about it but my sister said we all had to evacuate when they came to make sure it wasn’t going to blow up. And they took it away. That was a close call I guess. My Father being the Air Raid Warden. Sometimes we got hit pretty bad near the Clyde. And my Father would go down there and I remember one time him just sitting telling my Mother about it. I don’t think I was supposed to be listening. But he was talking about limbs all over the place and dead bodies because it had really been badly bombed down there near the shipbuilding in Dumbarton

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

It was incredible, the place (Clydebank) was absolutely devastated. Even although I was young, I can remember all the bombed houses and rubble everywhere. It was a massive playground for us. You can imagine, we got up to all sorts in the old, bombed buildings and my Mother and my Dad would’ve murdered us if they knew half the things we got up to. It was dangerous and we weren’t supposed to get into them, but we used to get in by hook or by crook somehow, they were maybe cordoned off by wood, but we still managed.

Next door to us was badly bomb damaged, the building was still standing but the inside was virtually away.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

In the close there lived a lady who was Irish, she was from Eire, and when the bombs were falling on the 13th or 14th of March 1940, one of the bombs fell on the bridge over the Kelvin beside the Art Galleries, destroying it completely. It was a land mine, and two of my Uncles were in my parents’ apartment and the walls came in until they were about 19 or 20 inches. These were stone tenements built in the 1880s and if they’d come in another two or three inches, the whole building would’ve come down. And then they went out again. My Uncles experienced that because they were watching the flak (aircraft defence cannon) that was going up on these German bombers. However, the Irish lady she was saying out loud how much she was praying for these poor boys up there in the sky and my Aunt Catherine who was quick off the mark- she said to her ‘Well, if you’re that keen on them, why don’t you go out and bloody well join them!’ So that happened in the dunnie in 97 Otago Street. They were a real labyrinth, so we spent time playing Cowboys and Indians down there, Cops and Robbers.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

During the war there was a lot of bombing, different types of bombing but particularly what was effective was called the Stukas which were low level bombers. They came across fairly low, and did do a dive, and dropped a bomb with pinpoint accuracy.

One of the means of defending strategic targets was to set up balloons outside the thing. They were all around various strategic places. There was a trailer lorry and they filled the thing with hydrogen and it was hoisted. If you were flying a dive bomber and you knew there were balloons above you, you knew bloody well there was a great big cable somewhere which you couldn’t see. And as you went into your dive and came out, if you actually touched the cable, you were dead. So it discouraged the average sensible bomber pilot and kept them higher. So that was I think the motive behind these and they were set up particularly at Scapa Flow in Orkney to defend the fleet.

Ralph Risk, born 1932, brought up in Pollokshields, Tyndrum, and Tarbert

Kent Street, you know where the Barras is, part of Kent Street was bombed. It was the left hand side of it and I think there was two or three people killed. We were told when we were going to school don’t go Kent Street way because it was bombed.

I was scared all the time, it was scary

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

But during the bombing. We went up into the hills. Pitch dark. Course with my blind grandfather trailing him along. Up into the hills above Greenock. Getting away from the bombing.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

One thing we did do when you had bombing. Anti-aircraft things, shrapnel would come out of the guns and land on the pavements. And there was all this stuff and we used to pick that up and collect it.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

My Father wasn’t [enrolled in the armed forces] because he had a medical problem pre-war which precluded him from serving in the war. My Mother, I know, took part in the fire watching. She worked for the railway at the time, I think it was L.N.E.R. pre-British Rail. My Dad was involved in the Clydebank Blitz because he worked for an undertakers. It was a car hire and undertakers’ business that he was the garage foreman for. So I know from talking to him that he had been involved in removing bodies from the Blitz in Clydebank. I think it had a fairly lasting effect on him to be honest. My Father’s two brothers also served in the war, both in the R.A.F. I think. My Mother had no brothers or sisters. However, her Grandfather was killed in Gallipoli just after she was born.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

A group of Clydebank children at Carbeth where the huts were requisitioned to house the children

I remember that the bridge over the river Kelvin, on Kelvin Wat through Kelvingrove Park, was hit by, what people said was a landmine but might have been a bomb, and all the windows on Sauchiehall Street, facing the Park, were blown in. This resulted in some mesh type material being stuck to the glass on the windows at the landings on all the stairs of Blantyre Street. My recollection is that this was not removed until a few years post-war. There was a ruined Church at the corner of Old Dumbarton Road and Argyll Street, right by the EWS Tank, but I believe the story is it was destroyed by fire and not bombs.

Bombed out buildings were the joy of my life. As a terrible tomboy I, along with a crowd of boys played in the bombed buildings whenever we could. I have been chased off a few by warders trying to stop us from harming ourselves but we loved it. I used to collect silver paper-wrappers from chocolates before the war. I incorporated these in my paper works of art.. Then we were told not to pick up shiny pieces of paper because they might be dangerous. I didn't think much of that.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

I was born in Clydebank in 1937. Where I was brought up is a long story. After the Blitz in 1941 we were evacuated to Helensburgh as we lost everything in the Blitz. I went to 9 schools between the age of 4 and 11. My parents split up and remember accommodation was scarce. My mother at one time asked to sleep in the police station, so I was shunted from pillar to post sometimes with a relative but other times with strangers.

Interesting now that you have mentioned a siren suit, I do remember that name, not sure if I wore one. I had a Mickey Mouse gas mask though, with lovely turquoise at the mouthpiece I recall. On the 13th March 1941 Mum, Robert and I were at the La Scala watching a Shirley Temple movie. My cousins have since told me that I won a Shirley Temple contest prior to the Blitz..That was where I first heard the bombs and my first really vivid memory. Mum picked me up and threw me under the seat. My understanding was that we had a young boy who lived in our close at 24 Second Avenue with us that night. I believe he was the only one of his family to stay alive. The dance hall across the way, had had two direct hits and people were coming in and walking like zombies down the aisle. I found that very frightening. My Dad was working at Singers and on his way to the La Scala he had to drop onto the ground three or four times as bombs fell around him. Miraculously no one in our greater family were killed.

I do have vague memories of the shelters, but I think I probably heard people talking about it. One story was of a friend who was asked to bring down some tins of fruit so she had loaded her apron with as many as she could carry and as she got to the entrance of the shelter, she heard the incendiary bomb and the contents of her apron up in the air. Those in the shelter thought they had been hit.

Matilda Jane Holmes, born 1937, brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh, and other places

Friday 14th March 1941

In the morning we had breakfast and heard the radio report a heavy raid on Clydeside. We went off with our cases for the school bus. At school, we learned that the raid on Clydebank had been severe and transport had been interrupted (no trains between Helensburgh and Clydebank). After school at 4.00pm we met together and went to the station and tried to phone home, but all the lines were dead. We discussed what we should do - return to Garelochead or try to get a bus to Clydebank. Eventually we decided on the latter and eventually boarded a packed double-decker bound for Glasgow.

We encountered the first bomb damage at Bowling - part of the tenement in ruins and smoking, also black smoke from a burning oil tank at Old Kilpatrick. The bus terminated at Dalmiur where there were many badly damaged houses,dust and smoke, fire engines etc. We became very concerned about the folks at home, as we walked through Dalmuir and Clydebank Main Street, to Taylor Street We were very glad to see the house still standing, so hopefully the folks were OK, however, the windows were boarded up. We were delighted to see our Mum and Dad and Uncle Willie, but they were aghast to see us! The house was without water supply, gas and electricity, but a water-cart had made a delivery and the folks had a portable stove.

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

I have no recollection of the Clydebank Blitz which started in March 1941 but it may have been a reason for our evacuation. I don’t remember which month of 1941 we went to Milngavie. I do remember my Father holding me at our front room window after a raid when, I think, a munition ship was hit in Yorkhill docks and the flames could be seen rising above the Sick Children’s Hospital at Yorkhill. I remember well the air raid sirens warning and also the all-clear when danger had passed. We were 1 floor, up in a 3-storey tenement and, for some strange reason all the neighbours congregated in our lobby instead of the air raid shelter or even our close which was shored up with scaffolding. When I was older and after the War, I thought this was rather silly. I had a siren suit but did not know enough to be scared, however, my parents, and the neighbours, did not transmit any fear that I remember.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

I remember one night when brother, Willie drew my attention to the searchlights that were criss-crossing the sky. In one the beams we actually saw an enemy aircraft. It took avoiding action to escape from the light. At the same time, the ‘Ack Ack’ (anti-aircraft) guns were firing and the noise was deafening. We thought that the enemy were aiming for the I.C.I works in Castle Street, opposite Garngad Road, which was only a quarter of a mile from where we lived. The I.C.I chemical works would have been a satisfactory target for the Germans if they had dropped their bombs on that night. The flight crews would have probably got Iron Crosses if they had succeeded. On going along Garngad Road the next day, I was able to pick up pieces of shrapnel which had fallen from the sky, the by-product of exploding anti-aircraft shells.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

We had the ground floor flat and the neighbours came into our close, I don’t know why. There was something to stop the bombs coming into the close. We never went to the shelter. We didn’t like air raid shelters they were crowded. It was sociable people coming into the close. There was a heavy curtain and as boys we looked out and watched the lights and the bullets trying to hit the planes. It was exciting. The nearest bomb was round the corner in Allen Street.

We lived opposite the gas works with one of the big storage tanks. Once a bomb dropped on the gas works but didn’t go off because it landed in a pile of sand just over the wall opposite our house. So we’d all have gone. It had gone off the end of us, they never got the gasworks or the yards that they were after.

There were occasional dog fights. The planes were all propeller jobs and they were slow. You watched them float across the sky. We watched them it was exciting. The trace bullets trying to get them.

My mate’s family were bombed out there. They weren’t hurt but they were fed up and immigrated to Canada straight after that. He was called Jim Sherriff.

Davie Walker, born 1934, brought up Bridgeton, Glasgow

There was a strong feeling that there would be a second raid that night, so after some food, father said that we should try right away to get back to Garelochhead and he accompanied us to Glasgow Road to try for a bus. People were streaming west carrying goods and cases, leaving the town. There was very little transport - perhaps one or two double-decker buses - packed, and not stopping. We waited until about 7.30pm as it started to get dark and then father said we should all return to the house.

Back at the house we all had a snack and the sirenssounded about 8.30pm. Tom and I took ourplaces under a large strong dining room table while the folkssat on chairsin the hall almost under the stairs. (My parents had been offered an airraid shelter before the war, but hadfoolishly decided not to get one.)Uncle Willie, then about aged 50 and not very fit, was an auxiliary warden (he had a helmet and gas mask) and went to the front door to watch the street and surrounding area. Soon the heavy sound of aircraft was heard, accompanied by fairly loud explosions of bombs and anti-aircraft fire (this was probably from the Polish destroyer, ORP Piorun,then in John Brown'sdock,nearby). The noise became quite intense and probably around midnight, father said we should leave the house and seek an air-raid shelter. There was an Anderson Shelter in a back garden, just two doors up (Mr and Mrs Connell). We ran out the back door covering our heads with our hands and found the shelter almost full, but Tom, Mum and I were admitted while fatherremained outside with some othermen, under a sand-bagged entrance.The shelter was very cramped (I sat on someone's knees). The noise lasted all night but eventually it became quieter and the "All Clear" sounded about 6.00am.

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

We returned to the house, which had sustained further window damage, and we had a breakfast. Then Uncle Willie and I had a walk around the immediate Whitecrook area. There was no substantial damage in Taylor Street but an incendiary bomb had fallen in the middle of the street and had been extinguished by a warden using a sand bag. There was lots of debris in the area, but the worst damage was in Whitecrook Street where a four-storey tenement had the middle completely blown down by a parachute mine (around 16 people killed in this street). I picked up two bright metal bomb or anti-aircraft splinters (one of which I still have - now rusty!)

Roderick MacDuff recalling testimony on behalf of his late father, Iain Blair MacDuff, born 1927, and brought up Clydebank and Garelochhead

I remember during the war my Mother and a neighbour hanging out their washing. And they were both in tears because the neighbour’s brother had just been killed. I started school in 1941 in the January and I kind of remember round about then because just after I had started the school was bombed at the Clydebank Blitz. So our school was bombed, and our school was closed for quite a while.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick