The housing situation at the start of WWII in Glasgow and the surrounding area mirrored that of many other industrial areas of Britain. Home was, for many, a legacy of cheaply constructed 19th century buildings, built for workers coming to cities during the Industrial Revolution. Squalor was one of the five giants identified in the Beveridge Report as holding back progress in housing in Britain in the 1940s. This was compounded by a halt in house building during WWI, followed by a ‘Homes For Heroes’ programme that was weakened in the 1920s and 1930s by a number of factors. This was marked by underspending in local authorities, the interwar Depression, and by what some regarded as stringent rules for securing a council house. This meant that people who did not have a steady job, a common situation at the time, could not get leases. There was also an ideological move away from public spending in the early 1930s, which meant that most of the houses being built were privately owned. This was the time when many three-bedroomed semi-detached houses were built in the suburbs for those that could afford them. Only 18 per cent of manual workers owned their own home. Slum clearance far exceeded house building during the inter-war period. Many people let out rooms to people in need of homes as a means to subsidise their own incomes. This contributed to overcrowded and unhealthy living conditions for many people.

During WWII, house building came almost to a standstill again, as two thirds of the skilled building workforce went into the armed forces, and building materials were in short supply. Those builders that were working were employed on government contracts. In Glasgow, there was an influx of war-workers from villages and towns across Scotland. The population grew from one million one hundred thousand, in 1939, to one million three hundred thousand at the start of 1940. There was a deliberate policy of getting people to work in armaments and engineering works in Glasgow; this saw almost a quarter of a million people moving into the city during WWII. Unlike in other areas of Britain, there was no large-scale scheme to build houses for these people. Some workers were rented houses in Clydebank, after the Blitz there in early 1941, only to have to leave as people returned home when the threat of bombing lessened. The Rolls-Royce factory at Hillington had a purpose-built estate, but many workers found the rents too expensive and chose to live further afield. This brought about a situation where people had either to be housed in extortionately high rented accommodation through their workplace, or to rent single or multiple rooms in people’s homes, often inferior in quality, and also for a disproportionally expensive fee. Little wonder that these workers sometimes struggled with rent as work tailed off towards the end of the war, and evictions happened as a result of this.

The aerial bombardment of Britain destroyed two hundred thousand homes. In Glasgow, between 1941 and 1943, six thousand eight hundred and thirty-five homes were destroyed and twenty thousand suffered minor damage. The Clydebank Blitz on the 13th and 14th of March 1941, resulted in the destruction of a huge percentage of its housing. There were four thousand houses destroyed, four thousand five hundred homes were severely damaged, and three thousand five hundred suffered serious to mild damage. In total only seven houses out of a twelve thousand strong housing stock remained completely undamaged. The Greenock Blitz on the nights of the 6th and the 7th of May 1941 brought about the destruction of five thousand homes, with twenty-five thousand suffering damage. Homes in other parts of Glasgow and the surrounding area were also damaged or destroyed during this time. The people of Clydebank who survived the bombing were evacuated en masse, with forty-eight thousand leaving the town and many were never to return there again. These people were bused to temporary reception centres and then went on to either stay with friends or family, or move out to places as far apart as Stirlingshire, Helensburgh, and Hamilton. Others, along with people from other bombed out areas nearby, found themselves in sub-standard and expensive accommodation closer to home.

From 1943, the Government tried to mitigate the housing problems by requisitioning houses and flats, but the effectiveness of this scheme did seem to depend on the local authority. Some were regarded as favouring the owners of these properties. Even when rules came in that meant that owners only had a fortnight to rent or sell empty houses, they often found ways to do just that. In Glasgow five hundred and seventy-five houses were requisitioned during the war, in comparison to only fifty-five requisitioned by the Corporation of Edinburgh. People were selected from the direst of circumstances to be housed in requisitioned houses and their rents were sometimes subsidised by the corporation, and in turn, the Department of Health. There was a case, at the end of the war, in which some private landlords looked to their own financial interest as opposed to the common good. Returning servicemen, a group whose rooms or homes were often filled by their families renting it out during the war, were put out of their accommodations in Largs to make way for holidaymakers. The corporation of the town complained to the Department of Health regarding this incident.

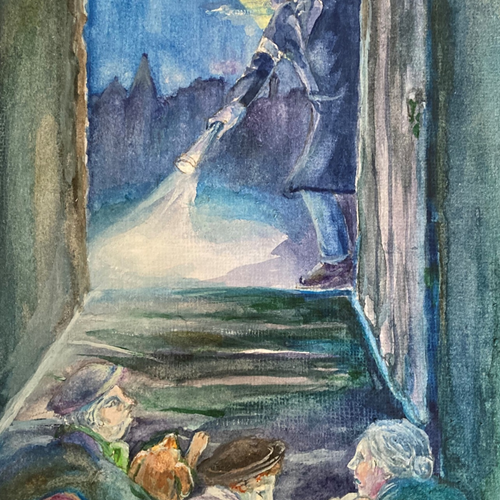

Squatting in properties happened in the West of Scotland, during the war, as a reaction to the housing difficulties of the time, but could end in prosecutions as the laws on squatting were stricter in Scotland than in England. For example, there was a squat in Greenock, in 1943, where the occupants had made great improvements to the property and were refusing to leave until they got alternative accommodation. They were eventually evicted from the property. At the end of the war, some POW and army camps were taken over by people in need of homes. The earliest example of that in Scotland was in 1945. This certainly happened at former POW camps at Patterton, East Renfrewshire, and at Pennylands, on the Dumfries House Estate near Cumnock and Auchinleck, Ayrshire. The wartime situation, in terms of housing in Glasgow and the surrounding area, was fraught with difficulties, some of which were to continue well into the post-war period.

Childhood Memories

“Housing”

The apartment had a recess bed, two chairs, sink. You had to wash at the sink. We had like a little zinc bath that my Mother used to bath me in. When we first moved to that house, my Mother was delighted getting a room and kitchen. It was two nice big rooms and the hall had a bunker in so that was good and my Uncle helped us with the flitting. He had a coal lorry, not that there was much to take, a mattress, a couple of chairs, a sideboard, a table. How we had all that in one room…however, that was the stuff she got taken up. So we decided I was to sleep in this recess bed in what was to be the kitchen. We had a big range. The next day I was itching. There was bugs, there was bed bugs. They live in the wall and infested our things, so it all had to get thrown out. So we didn’t have a bed. So, the sanitary men came and put paint on the walls, like green paint, inside this bed recess. I think it had something DDT in it or something like that and that cured that problem. But she had to get a bed. Somebody said you can have this, it was like an iron bedstead, like an old brass bed. It would cost a fortune now. So that was in the front room this great big bed and then she had to get a mattress. She went down to the Co-op in Bridge Street and saw she couldn’t afford one. A man took pity on her and said, ‘Look we’ve got one here but it’s got a bit of oil on it so she got it for a cheap price.

You know, I can remember washing my feet with my socks on to get them clean at the same time. That was in the room and kitchen.

We had to use a potty, a chamber pot, and it got emptied in the morning. There were three families in the stairs and the people in the middle. My Mother reckoned the father had T.B. and she didn’t want us using the toilet. She cleaned it and all that sort of thing. But she didn’t want us using it.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

It was a two room and kitchen as they called them in those days. My Aunt was there with her husband and her two sons. They were a few years older than my sister. So, they were about six or seven years older than me. My Mother’s brother was there. He was an opera singer. He used to sing in the Carl Rosa Opera. Then my Mum came with my sister and I. So there was quite a crowd of us. But we managed fine and everybody seemed to be well fed and cared for. There was an inside toilet which was really something.

There was a range of course, black. It had to be black leaded once a week, I think. And along the edge had to be done with I think a Brillo pad, I suppose, or steel wool anyway. And rubbed and made to shine. And then the big kettle went on the fire. There was a fire in it and the big kettle went on to boil the water for the tea. And I remember a big pot. Whether that was for soup or not I don’t know. A big kind of cauldron thing.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

It was a house and they called them a garret, on the roof. It was a house like that. I don’t remember how big it was. My older brother he stayed in it with my Mum and I and my brother Joseph. He was born in Rothesay in 1944, so it was obviously not a bad size… Right across from the house was a school that my brother went to. I was too young to go to school… I remember there was a wall in front of our house and I fell off this and broke my arm… I remember the Castle it wasn’t far from us.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

Well it had two bedrooms one living room and one bath. It was quite a good size bathroom back then. And we kept the coal in a cupboard. The coal man would come with a coal bag on his back. We also had a coal bunker outside. We had no fridge until I was almost twelve. We got a very small refrigerator. I shared the room with two sisters. And we had a sitting room and my parents would sleep on a pull-out couch. Settee. It was a nice house. I was very happy there. And you know it had a nice yard. The people upstairs had the side yard.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

My grandparents lived in a two-apartment house in Back Templehill. The lavatory was in the backyard. The cooking was done on a gas ring and an old coal fired grate. My mother had reluctantly to go to Troon with us kids. She hated it. The accommodation was hardly adequate. My dad had insisted that we all had to go to Troon in order to avoid the danger from air raids. When I think of it now my Dad had a nerve expecting us to live with my grandparents under the conditions that prevailed. My gran was in her late seventies, my granddad must have been about eighty, deaf as a post and smoke Gallagher’s Thick Black tobacco in his pipe. He would not allow the window to be opened. I can still remember the combined smell of stale tobacco, wood and coal smoke from the occasional “blow-down” from the chimney.

There were five (?) of us kids, with our parents, staying with Grannie and Granda Power. The two-apartment flat was on the ground floor, first left, in the close. Three other flats comprised the small tenement, one across the close and the other two, above, were accessed by way of stairs in the backcourt. Adjacent to the kitchen, in the back court, were a coal cellar and next to this, a lavatory.

Both rooms in the flat had double inset beds. These beds were in recesses in each room and would be curtained off during the day, giving the impression of a room with no bed. My grandparents occupied the front room and the rest of us slept in the back room. Makeshift beds had to be made on the floor because we could not all fit into the inset bed in our room. Our room had a cast iron range and there was always a kettle of water on the grate, this being the only source of hot water. Conditions were primitive by today’s standards but acceptable then.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

My Granny was one of them (homeless during the war) and she had about four of a family still staying with her. They were quickly rehoused in Old Kilpatrick. I do remember somebody taking me up to Clydebank. And I remember a tenement had been sliced down by the bomb and I thought it was very funny because there was a toilet, a lavatory pan, just at the edge where the bomb had split the building.

Our house had blast damage but we were able to go back to it after a couple of months. I remember there was a big hole in one of the internal walls and this is what it was. It was blast damage.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

We lived in a Nissen hut in Helensburgh until we found some other housing. It was very cold. We then went to the corner of Argyle and Sinclair Streets for a while then we lived in Mill Glen right next to the Hermitage. I loved it there.

Matilda Jane Holmes, born 1937, brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh, and other places