WWII conscription began in May 1939, as it became apparent to Neville Chamberlin and his government that war was inevitable; men between the ages of twenty years and twenty-two years were required to submit to military training. On the day that war was declared, The National Service (Armed Forces) Act, 1939, brought in conscription for all males between the ages of sixteen and forty-one. Those in reserved occupations and those who were medically unfit received exemptions. People who were conscientious objectors appeared before tribunals; if they were successful, they were given non-combatant jobs. Conscription helped greatly to increase the number of men in active service during the first year of the war.

In December 1941, Parliament passed a second National Service Act. It broadened the remit of conscription further by making all unmarried women and all childless widows between the ages of twenty and thirty liable to call-up. Men were now required to do some form of National Service up to the age of sixty, which included military service for those under the age of fifty-one.

The effects on families of men away at war during WWII were many. Marriages had often been entered into young during the marriage boom in the UK at the start of WWII, and before the spouses had really got to know one another. This resulted in marriages lacking in essential elements of resilience. Men and women often did not comprehend the realities of each other’s wars. Men were sometimes under the impression that their wives had the easy side of the bargain and did not appreciate the arduous work and fear that they were experiencing. Likewise, women would, in some cases, have found it hard to imagine what their husbands had witnessed and been through as members of the armed forces.

Members of the armed forces were given little leave during WWII, and the leave system was not set up with families in mind. Often, leave was fleetingly short and not designed to coincide with any time off work that wives may have been given. Sometimes children would not see their father for years, or did not meet them until they came back from the war. This resulted in some children only meeting their fathers at the end of the war and not really knowing them, or even in children regarding their fathers as complete strangers. In some cases, family bonds took years to form or repair; sometimes they were never formed or mended.

Extra-marital affairs happened both on the home front and during service abroad. Separation, loneliness, and the threat of imminent death contributed to their prevalence during this period. Affairs were known to result in children. Some marriages survived these difficulties as people were forgiving and realised that the circumstances, during that time, were exceptional. One respondent recalls that on arriving home to Glasgow, one husband accepted the two younger children as his own, knowing that they had been the result of his wife’s wartime affair. The mores of the day meant that the children did not find this out until many decades later.

Men were sometimes traumatised by their experiences during the war, and some never recovered. Others suffered terrible physical injuries which affected them for the rest of their lives. These mental and physical issues could bring about family problems, such as mental and physical abuse. It also might result in wives looking after broken men for the rest of their lives. There was little understanding or support with those who had mental health problems during this era. These circumstances could have adverse effects on young children, both during and after the war. Children may also have had older siblings that were away to war. There were occasions when young men joined up below the official age, whilst effectively still children themselves, and this caused distress to their families. The death of a father or child, and/or other family members, was an all-too familiar occurrence and brought trauma to many wartime families.

The National Service Act, 9141, required that all women between the ages of 18 and 60 years old had to be registered and record their family occupations. Initially this was just single women. By 1943, ninety per cent of single women and eighty percent of married women were employed in war work of some nature. Women were never supposed to come under enemy fire, but some did die on active service, with auxiliary armed force services, leaving families bereft of mothers, sisters and aunts. Married women also conducted dangerous work in munitions factories and other home front work placements, and women soon made up one third of workers in metals and chemicals factories. Some men, however, who were in what was known as ‘reserved occupations’, were prevented from going to war. Some men found this emasculating, and feared that they would be viewed as ‘shirkers’ by the public, and indeed, some were accused of avoiding ‘doing their duty’ in the beginning. This may have had its implications for the family life of these men. It is thought that the perceived bravery, and consequently the self-esteem of these men, improved after the Blitz and when people realised the importance of the work that they were doing for the war-effort.

Married women and men in Glasgow and the surrounding area often worked long hours during WWII. Factories producing war materials in and around the Glasgow area included the Rolls Royce factory at Hillington, which built Merlin engines for Spitfires and Lancaster Bombers, the Dalbeattie explosives factories, the torpedo factory in Greenock, the Singer Sewing Machine factory in Clydebank which was converted to produce munitions, Cardonald in Paisley which produced war ships, and many more. One female respondent remembers regularly working twelve-hour shifts at the Rolls Royce factory in Glasgow. People would also work in occupations such as the ARP, the air warden service, and the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, in addition to their full-time jobs.

WWII was the first time the term ‘latch key kid’ was used. The term describes young children having to let themselves into their homes whilst parents were away at work or war. Children who stayed at home often had to be independent during these years and some took on household chores and duties. Children could leave school at fourteen to start jobs in some work environments and would work long hours, sometimes on different shifts to their parents or siblings. Others were evacuated and experienced a different kind of war. Mothers and fathers would have missed their children, and vice versa, for these reasons. Perhaps unsurprisingly, divorce rates peaked at the end of WWII. Some marriages did survive and some families, did, on the face of it at least, recover from their war experiences, which varied vastly in intensity, and go on to live relatively normal lives. Others did not.

Childhood Memories

“Impact on families”

I had three uncles; one was a ship’s surgeon on a troop ship. He was torpedoed. And another Uncle who was a gunner in the Army. He was in Burma. And another Uncle who was in the Royal Navy. My Dad didn’t pass the medical examination. He would’ve gone but he was too low a grade to be accepted in any of the forces. My Mum was happy, but he wasn’t, he was disappointed.

My best friend’s brother was killed. He was in the Air Force. He was only about 19 or 20; he had been last seen entering a hall and wasn’t seen again. I remember that. We were only about 7 or 8 years old and he was about 19.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

He was pulled up for the American Army when he was 19 (his Uncle Jimmy). He was working in Weir’s in Cathcart as an apprentice. And he got called up to go to the American Embassy in Edinburgh. And then three weeks later he was shipped out to the United States for military training. He didn’t see any action lucky enough because he was on a troop ship going to the Philippines when the Americans dropped the atom bomb. So the war was basically over by the time he got to the Philippines.

My Father, he was demobbed in Munster, Germany. And I used to have my Father’s old army great coat. That was used as an extra blanket for us in the winter time. That was on the bed for me and my sister. A great big heavy khaki horrible itchy thing. But it kept you warm. That was before continental quilts were ever invented.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

My Dad, unfortunately, had been a prisoner of war. He was captured in St Valery in France and marched into Poland where he was kept in a prisoner of war camp. He didn’t speak much about it at all. But I did get the impression that some very unpleasant things had happened to him. And subsequently discovered that instead of being de-mobbed in 1945, he had actually been sent back in 1943 as part of a Red Cross exchange where prisoners on both sides who had health issues were swapped through the Red Cross, so German prisoners in the UK would be sent back and British prisoners in Germany would be sent back. I believe that’s how my Father came home early.

Because he was part of the Royal Army Medical Core. When he arrived at the camp in Poland, there was a big hospital in the camp which treated German soldiers. And because of his background in being a Medic, he was put to work in the German hospital. And he actually had pictures of him with German soldiers who he was looking after and nursing. And I recall one of the things he said was that a lot of these German soldiers loathed the Nazi regime just as much as the people who were suffering under them. And while they were patriotic Germans, they weren’t Nazis. He spoke a little German having treated some of the German soldiers. He was able to speak to them in basic terms. Apart from that he spoke very little about his experiences.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

My Father, he was called up just before I was born and he had to report up to Perth. And I believe at first, he was in the Black Watch in the Infantry Regiment. But what I remember he was in the Royal Scots.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

My older brother was in the Royal Navy. He was at war. My other brother, he’s four years older than I am. He did his National Service later on and he was in Ireland.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

My brother, one brother was in the Navy, one was in the Merchant Navy and one in the RAF. And my older sister’s husband, and he was killed at Anzio. Twenty-three he was.

You did hear about people getting killed. I think they called it the buff letter. You know it was a buff colour. And you knew this was the telegram to tell them that their husband, or their son or whatever was killed.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

I remember my Uncle Wullie coming back from the Navy. That was a big thing. He arrived still with his uniform on you know. He came into our house in Somerville Street. I remember. I’ll never forget. He’d a big…I think it was a Navy issue. It was a big case. It was a kinda lime green case. You know. Heavy duty case. And he opened it up in the living room. Like that. You know. And me and two of my brothers and Jack, aye Jack would be there. His son. And he opened it up and it was aw the sweets you know boilings and aw that (laughs).

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

Not nearly as much as my parents must’ve had. I don’t think my imagination would conceive of my heroic big brothers having trouble. In a way the fact that Tom was a flying boat pilot he was involved, I believe, in the battle of the Atlantic a little bit.

My brother John. I was only really aware after the event that he had landed, not on D-Day, but later.

My older sister got married and joined the WVS and worked in Stirling. My eldest brother went into the Air Force and became a pilot and travelled the world in flying boats. He was a flying boat pilot. His travels left me always anxious to see other parts of the world. He was based in Ceylon and flew to Perth in Western Australia. Which at the time was almost Amy Johnson type flying. It was a Catalina, a long range plane which was almost unheard of. He joined the Air Force and my second brother joined the Marines in 1944 or thereby. He was in Holland and Belgium fighting... And I was still too young to do anything.

So, it was an interesting life, second-hand, and so many things happened… “The end of the war came so everybody returned home and set about their life.

Risk Ralph, born 1932, brought up Pollokshields, Tyndrum and Tarbert

They were both in the ATS and both stationed in England. Although my Aunt went to OTC (Officer Training College), and she was transferred to Germany where she was an officer of the British Army on the Rhine. And she was there for three or four years and then she came back to Glasgow to look after her Mother, my Grandmother. And she became a police officer and she was in the first group of ladies who became detectives in the Glasgow police force and she worked at Glasgow Central and Maryhill and no doubt one or two other places, eventually ending up as an investigating officer on fraud activities.

My other Aunt, she was in England, and she was the whole British Army rolled into one. A very dominant fun-loving character. Loved us all to death. She lived in Park Road just round the corner from Gibson Street, so we always stayed very close to each other when we were all in Glasgow. And today, none of my relatives live in Glasgow, not one.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

Listening to the radio regularly and my parents listened to the radio and you asked questions and they explained things to you. And I suppose the first time it really hit me was, we lived in a tenement and upstairs was a family and their son joined the R.A.F. And he went missing. And you know how friendly people are living in a tenement. So we knew this family really, really well. And so that’s the first time probably maybe a couple of years into the war when he was killed. And I think that’s when I suppose I got the implications of a war in a way that I think before that my life had been kind of normal. No different from before the war.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

My Father was a very unassuming man. He never talked much about his experience but he served in the Atlantic and Arctic Convoys and particularly on that infamous convoy PQ 17 when so many ships were lost. He was on one of the rescue ships, The Zamoli.

I don’t think the service of the Merchant Navy was ever properly recognised, and certainly he went through hell with that.

I’ll tell you one experience my Dad had. He was on a ship that was going from Glasgow to Boston, U.S.A., and he did the round trip. He was an engineer and there was something about the ship he didn’t like and he decided to leave and transfer to another ship. He was a civilian, although he was on war duty, so he had the choice as long as he was on a ship, he could serve on any ship he liked. So he got off the ship and on its next round trip, it sank in a storm. And you know if he hadn’t had that intuition, he was an Engineer, and there was something about the ship he didn’t like. He didn’t think it was seaworthy and he was right and on its next trip on the way back to Glasgow, it sank south of Iceland. No survivors, none whatsoever. They didn’t even get the boats off because I actually tracked down the surviving radio messages from the ship in the records and they said they were going down by the head and they were trying to launch boats and it just sank, no survivors ever found. That was it, no more radio transmissions. He sent a letter home and I have a copy of the letter and it says he wrote to his Mother. It said I’ll be home in time for my 21st birthday. And said I don’t like this ship, I won’t be going back on it, or something to that effect. And if he had taken that second round trip, I wouldn’t be talking to you right now. That’s how problematic sometimes these things can be.

My Grandfather was at Dunkirk again as a merchant marine. He was delivering supplies to Dunkirk. His ship was bombed. He was stranded and got off with the soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk.

Amazing stories. Lots of people have got stories like this.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

So, when I was three months old my father went to the war. Never saw again. Never came back. He got drowned in Naples. I was eighteen months old.

My own Uncle Peter had been a P.O.W. in Germany. He died. I’m sure there was a few tales to tell, but when you’re young you don’t really listen. I just remember he had to march through the snow in Germany, very cold and I think there was a lot of bad things happened on the march to women. And others getting left behind and things like that. But I wish I’d listened more.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up

My Father, he was in South Africa and Sicily in Italy. And I can remember when he did come home my sister said ‘I’m not staying in this house with that man. Because we had never been used to having a man in the house. But of course, we soon got used to him being in the house.

My brother-in-law did. My husband just missed it. My brother-in-law, he was in Germany for his National Service. I can remember my uncle doing his National Service and my Granny had died so he was brought home. He was in Germany too.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

I don’t remember too much. I do remember one time being woken up in the middle of the night and we went off to my Uncle’s house. He had gotten notice that he had to go to war and that’s the earliest memory I have.

My Uncle, my Mother’s brother joined the Marines. My Father was turned down due to problems with his knee.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

My Father’s brother went off, he joined the Scots Guards and he came back. In fact I still have a letter that he wrote to my Father from Italy in 1944. When they landed and were marching up to Italy, he wrote to my Father but he didn’t mention where he was. My Father had obviously said to him that he knew where they were. He had guessed it was Italy and in the letter my Uncle said, ‘You guessed right’. That’s when they were going up through Italy to Monte Cassino. I remember my Mother and Father getting a couple of Christmas cards from foreign places from friends of theirs that were at war. My Uncle came back alright. But there were quite a few from the village that didn’t come back. That were killed in the war.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

My brother, one brother was in the Navy, one was in the Merchant Navy and one in the RAF. And my older sister’s husband, and he was killed at Anzio. Twenty-three he was.

You did hear about people getting killed. I think they called it the buff letter. You know it was a buff colour. And you knew this was the telegram to tell them that their husband, or their son or whatever was killed.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

My Father’s two youngest brothers served in RAF I believe as ground crew. I met a friend at University in 1957 who told me that his Father had survived his ship being torpedoed on the Russian convoys but other than that no one close was involved other than as Air Raid Wardens like my Father. My Father at the start of the War was a bus driver, he had previously driven lorries, and during the War often drove ambulances as did his 2nd oldest brother. His 5th brother was a shopkeeper in Greenock.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

My Father, he was called up just before I was born and he had to report up to Perth. And I believe at first he was in the Black Watch in the Infantry Regiment. But what I remember he was in the Royal Scots.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

I remember my Uncle Wullie coming back from the Navy. That was a big thing. He arrived still with his uniform on you know. He came into our house in Somerville Street. I remember. I’ll never forget. He’d a big…I think it was a Navy issue. It was a big case. It was a kinda lime green case. You know. Heavy duty case. And he opened it up in the living room. Like that. You know. And me and two of my brothers and Jack, aye Jack would be there. His son. And he opened it up and it was aw the sweets you know boilings and aw that (laughs).

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

They were both in the ATS and both stationed in England. Although my Aunt went to OTC (Officer Training College), and she was transferred to Germany where she was an officer of the British Army on the Rhine. And she was there for three or four years and then she came back to Glasgow to look after her Mother, my Grandmother. And she became a police officer and she was in the first group of ladies who became detectives in the Glasgow police force and she worked at Glasgow Central and Maryhill and no doubt one or two other places, eventually ending up as an investigating officer on fraud activities.

My other Aunt, she was in England, and she was the whole British Army rolled into one. A very dominant fun loving character. Loved us all to death. She lived in Park Road just round the corner from Gibson Street, so we always stayed very close to each other when we were all in Glasgow. And today, none of my relatives live in Glasgow, not one.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

I don’t remember too much. I do remember one time being woken up in the middle of the night and we went off to my Uncle’s house. He had gotten notice that he had to go to war and that’s the earliest memory I have.

My Uncle, my Mother’s brother joined the Marines. My Father was turned down due to problems with his knee.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

My Father, he was in South Africa and Sicily in Italy. And I can remember when he did come home my sister said ‘I’m not staying in this house with that man. Because we had never been used to having a man in the house. But of course, we soon got used to him being in the house.

My brother-in-law did. My husband just missed it. My brother-in-law, he was in Germany for his National Service. I can remember my uncle doing his National Service and my Granny had died so he was brought home. He was in Germany Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

Listening to the radio regularly and my parents listened to the radio and you asked questions and they explained things to you. And I suppose the first time it really hit me was, we lived in a tenement and upstairs was a family and their son joined the R.A.F. And he went missing. And you know how friendly people are living in a tenement. So we knew this family really, really well. And so that’s the first time probably maybe a couple of years into the war when he was killed. And I think that’s when I suppose I got the implications of a war in a way that I think before that my life had been kind of normal. No different from before the war.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

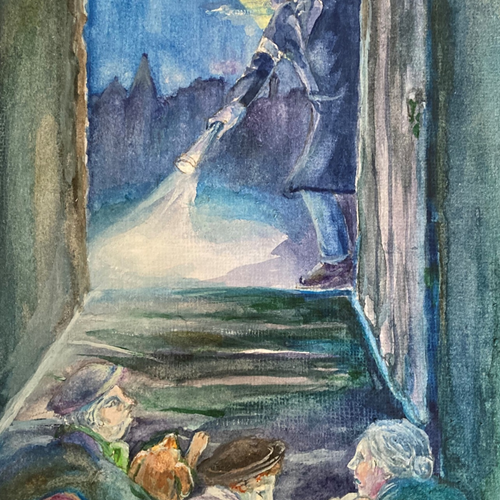

The Civil Defence rescue work in Clydebank came to an end when the Blitz ended. My dad’s nerves were very bad and although things were quiet in the Corps, he felt that he had had enough, he wanted out. All adults had to conform to Government regulations regarding what they could do. The Civil Defence was a reserved occupation and one was not allowed to leave unless there was work of national importance as an alternative. My dad had to argue his case before a tribunal which existed to examine requests for transfers to other work. He was good at debating, and although his education was lacking when it came to reading and writing, he could speak intelligently. He told the tribunal that he could do very important work as a welder and burner, in Troon, as a ship breaker. As the need for the Civil Defence rescue had virtually ceased in the West of Scotland area, he would be much better employed as an essential worker in Troon. He told the tribunal that there was a great need for burners in the shipyard there. This was true. My dad had checked with his contacts in Troon and verified that there were vacancies waiting to be filled. He knew that if he didn’t get away from the Civil Defence Corps he would go off his head. His appeal succeeded and he started work in Troon shipyard.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

I know that Ernie Valente and his oldest son from a big family, those two got taken away because they were Italian. I remember when we got back to Somerville Street, they were still away. The family were still there, they hated the Nazis as well the same as everybody else. Ernie used to work with cement in the Rothesay dock I thought he was a baker because every night he used to come in and he was pure white with cement.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

My father was a doctor who had qualified from Glasgow in 1942. Having been in the Glasgow University O.T.C. He was whisked away as a volunteer and ended up landing in North Africa with "Operation Torch. He was in Command of a Field Ambulance and was blown up during the Attack on Longstop Hill in Tunisia April 23 1943. As a result of this he always used a deaf aid (Which when I was young was a massive thing which was suspended from his under vest and lately was just a wee thing in his ear) and had been a bit shoogly for while. He was lucky as most of the men with him were killed. My mother and he had got married in 1942, as if he had been killed and married my mother would have received a pension, otherwise not.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow

Colin Stevenson (standing) and Peter McNaughton, class 2C, Hillhead High School.

For all it was 1950 sometimes I think that our society was still living in a sort of Victorian, pre-First World War era. At Christmas in my Aunt Agnes's house my father, my Uncle Colin (who I was called after) and my Uncle Duncan, plus a few drams, would be talking about the war. Even then I was aware that war for my uncles was the only real one and that the second war had been just a bit of a side show despite the fact that my Father had been wounded in the second one.

During this time there had been the invasion of Egypt with the French which the Americans made the UK back out off. At the same time I can remember listening to Imre Nagy the free Hungarian PM pleading for help from the West on the radio. I could not understand when my father said to me "No one will be going son". Imre Nagy was taken by the Russians to Moscow put on some sort of trial and then hung.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow

So, when I was three months old my father went to the war. Never saw again. Never came back. He got drowned in Naples. I was eighteen months old.

My own Uncle Peter had been a P.O.W. in Germany. He died. I’m sure there was a few tales to tell, but when you’re young you don’t really listen. I just remember he had to march through the snow in Germany, very cold and I think there was a lot of bad things happened on the march to women. And others getting left behind and things like that. But I wish I’d listened more.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

I do remember the day they came round and took away our railings from the front of our house. The whole country, they wanted the iron for making ammunition and things like that.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

He was pulled up for the American Army when he was 19 (his Uncle Jimmy). He was working in Weir’s in Cathcart as an apprentice. And he got called up to go to the American Embassy in Edinburgh. And then three weeks later he was shipped out to the United States for military training. He didn’t see any action lucky enough because he was on a troop ship going to the Philippines when the Americans dropped the atom bomb. So, the war was basically over by the time he got to the Philippines.

My Father, he was demobbed in Munster, Germany. And I used to have my Father’s old army great coat. That was used as an extra blanket for us in the winter time. That was on the bed for me and my sister. A great big heavy khaki horrible itchy thing. But it kept you warm. That was before continental quilts were ever invented.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

My older brother was in the Royal Navy. He was at war. My other brother, he’s four years older than I am. He did his National Service later on and he was in Ireland.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

My Father was a very unassuming man. He never talked much about his experience but he served in the Atlantic and Arctic Convoys and particularly on that infamous convoy PQ 17 when so many ships were lost. He was on one of the rescue ships, The Zamoli.

I don’t think the service of the Merchant Navy was ever properly recognised, and certainly he went through hell with that.

I’ll tell you one experience my Dad had. He was on a ship that was going from Glasgow to Boston, U.S.A., and he did the round trip. He was an engineer and there was something about the ship he didn’t like and he decided to leave and transfer to another ship. He was a civilian, although he was on war duty, so he had the choice as long as he was on a ship, he could serve on any ship he liked. So, he got off the ship and on its next round trip, it sank in a storm. And you know if he hadn’t had that intuition, he was an Engineer, and there was something about the ship he didn’t like. He didn’t think it was seaworthy and he was right and on its next trip on the way back to Glasgow, it sank south of Iceland. No survivors, none whatsoever. They didn’t even get the boats off because I actually tracked down the surviving radio messages from the ship in the records and they said they were going down by the head and they were trying to launch boats and it just sank, no survivors ever found. That was it, no more radio transmissions. He sent a letter home and I have a copy of the letter and it says he wrote to his Mother. It said I’ll be home in time for my 21st birthday. And said I don’t like this ship, I won’t be going back on it, or something to that effect. And if he had taken that second round trip, I wouldn’t be talking to you right now. That’s how problematic sometimes these things can be.

My Grandfather was at Dunkirk again as a merchant marine. He was delivering supplies to Dunkirk. His ship was bombed. He was stranded and got off with the soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk.”

Amazing stories. Lots of people have got stories like this.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

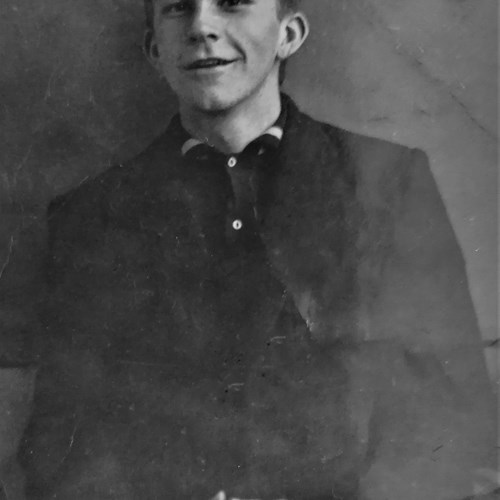

Heather Bovell, aged 1, c.1949

My Dad, unfortunately, had been a prisoner of war. He was captured in St Valery in France and marched into Poland where he was kept in a prisoner of war camp. He didn’t speak much about it at all. But I did get the impression that some very unpleasant things had happened to him. And subsequently discovered that instead of being de-mobbed in 1945, he had actually been sent back in 1943 as part of a Red Cross exchange where prisoners on both sides who had health issues were swapped through the Red Cross, so German prisoners in the UK would be sent back and British prisoners in Germany would be sent back. I believe that’s how my Father came home early.

Because he was part of the Royal Army Medical Core. When he arrived at the camp in Poland, there was a big hospital in the camp which treated German soldiers. And because of his background in being a Medic, he was put to work in the German hospital. And he actually had pictures of him with German soldiers who he was looking after and nursing. And I recall one of the things he said was that a lot of these German soldiers loathed the Nazi regime just as much as the people who were suffering under them. And while they were patriotic Germans, they weren’t Nazis. He spoke a little German having treated some of the German soldiers. He was able to speak to them in basic terms. Apart from that he spoke very little about his experiences.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

My Father’s brother went off; he joined the Scots Guards and he came back. In fact, I still have a letter that he wrote to my Father from Italy in 1944. When they landed and were marching up to Italy, he wrote to my Father but he didn’t mention where he was. My Father had obviously said to him that he knew where they were. He had guessed it was Italy and in the letter my Uncle said, ‘You guessed right’. That’s when they were going up through Italy to Monte Cassino. I remember my Mother and Father getting a couple of Christmas cards from foreign places from friends of theirs that were at war. My Uncle came back alright. But there were quite a few from the village that didn’t come back. That were killed in the war.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

I remember that in the bungalow which was across the street there were Polish soldiers billeted there and we used to talk to them. Lovely, handsome Polish soldiers. I remember them very well. There were also Italian prisoners of war. I remember them giving me a present of a bracelet. They were billeted outside of Glasgow so I have no idea of how I got in touch with that one.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

I would’ve been about four or five. My Granny stayed at number 16 Commerce Street, three stairs up. And with being up that height her bedroom windows looked up on to the railway. And as a youngster I’d stand at the window and you saw the trains going out and in. And I’ve got a faint recollection you could see there were soldiers in them. You know they were quite far away, they were about two or three hundred yards and that is a memory I’ve got seeing that. The only other thing is I remember when my Dad was going from leave after being home and he was stationed up at Methil. And it was later I found out they left from Queen Street and I don’t know if I had any brothers and sisters there, but my Mother took us all out to the train. It was a corridor train with a corridor down the one side. And what I remember is the compartments were all full of servicemen and the air was blue with smoke. I think everybody smoked. So I’ve got that memory of that.

I remember the Prisoners of War coming home. There was a man up our close. I don’t know if he was caught by the Germans or the Japanese. But I remember another time the place was packed with people and this was another Prisoner of War coming home. Because they’d bunting across the street. I think he’d been a prisoner of the Japanese. And that would be late ‘45 early ‘46… I’d been on a bus at Glasgow Cross and saw these guys with a mark on their backs. And my Mother said that they were the German Prisoners of War. By that time, the war was over.

Alf Duffy, born 1940, brought up in the Gorbals and Pollok

Oh yes, you knew when there was a ship in the Clyde, the girls were all out. No disrespect to the girls. We had the Americans in Prestwick so we had them all the year round but if a ship, an American ship docked in the Clyde it got round like wildfire. And remember, these fellows, unlike the Brits when they came into town they had nylons, remember the girls didn’t have stockings during the war, they painted their legs. So they had nylons, chocolate, chewing gum, money, cigarettes. Cigarettes? I remember one time going into Liam’s Cafe in Skirving Street, Shawlands, and there was a sign ‘Cigarettes’, and running down to my cousin, Lily Lipton, saying, ‘Lily, get up to Liam’s Cafe quick, they’ve got cigarettes in’. This was probably the ‘50s, after the war.

Shortly after the war ended. Can’t remember the circumstances. But my mother took me down to Mrs Henry who was at the end. And I was introduced to these two ladies and a young girl my age. And it was the first time I ever, ever saw someone with numbers tattooed on their arm. And this little girl still had bite marks from the dogs. They’d come out of Belsen. And anyway, they settled in Glasgow. The young girl was very good. I mean she couldn’t speak a word of English. She ended up going to university. Became a pharmacist and sadly died just a few years ago.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

If you went into say Argyle Street way, you would see one or two(GIs) but it was only after the war when we went to Pollok and they had the Cowglen American Military thingamy. That was a couple of bus stops before we arrived at Pollok. But we didn’t really see them much unless you were older and went to the dancing I suppose.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

We had two friends who were in P.O.W camps. There was a camp quite near us I think it was Germans who were in there. I remember going on holiday to Filey to a Butlins Camp, going out horse-riding. And the pony that I was on just stuck his heels in and wouldn’t go any further. And a man came running over and walloped the rear end of the pony to make it go. And I think they were prisoners who were actually helping to build the Butlins camp at Filey. They weren’t wearing uniforms. Somebody said they were Germans building chalets and doing gardens. That would be 1947.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

I can’t remember if they were prisoners of war or what. I’m just not too sure but I remember lots of girls going up and talking to them through the railings. So I think they were prisoners of war, because it was a kind of brownish uniform they had on, like a battle dress. I can’t be more positive about that one. I have a funny feeling they were Italian and I think this is maybe why the girls were interested in them. But I remember going up one day, well Bellahouston was quite a bit away from where I lived, and you were walking but that’s about all I can tell you about the camp at Bellahouston Park.

George Burns, born 1926, brought up in Bridgeton then Kinning Park

There used to be a big fuel depot during the war and boats used to come in to refuel. And we used to stand at the bridge and if it was Americans coming up, we would say ‘Any gum chum?’ And if we went in with chewing gum my Mother would be mad because we’d been mooching. If it was a British soldier or a British sailor you asked if they’d any souvenirs. So, you’d get a button. There used to be barges going up and down the canal full of peanuts during or towards the end of the war. And if you were nice to them, you’d get a handful of peanuts.

And I remember I used to walk from Old Kilpatrick across to my aunt’s house in Inchinnan. Which was quite a walk when I think. I couldn’t do it now. But I used to do it during the war. So, the war ended ’45. I would be nine years of age. And I was walking over tae Inchinnan. During the war…I remember it was during the war ‘cause there was a German Prisoner of War worked in one of the farms. You could tell by his hat that he was a prisoner. And I used to always be a bit wary if he was in the front garden when I was passing.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

I remember there would be lots of trucks. And there would be British troops and American troops. There was a lot of Americans. And my mother pointed out one to me. I wasn’t exactly sure what was going on but she said that one of the trucks had a big sign that said, “Don’t clap for us we’re just the Britishers not the Americans” (laughs). It’s like everybody loved the Americans you know. Especially the young ladies. And we also had a lot of romances with the Dumbarton girls and the Americans.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

The part of the building on the right of us was used as a N.A.A.F.I. during the war. When war was over and I was allowed out to play, I used to sit at the front of the close and watch the people passing. The N.A.A.F.I. took up the three floors, the first being a restaurant/cafe with tables and chairs. The kitchen was on the ground floor and sometimes they left the back door open which was in the back court and us kids could look in. We used to watch all the different branches of the forces going in and out and the most popular for the children were the Americans. As soon as any appeared either out of the door or coming along Argyle Street, they were rushed at by the kids shouting 'Any gum chum' which seemed to amuse the Yanks, as we called them, and they would happily hand out any sweets they had in their pockets. One American soldier was chewing on a bar of Highland Toffee having just taken a bite and saw me sitting at the close and he walked over and held out the chewed toffee to me, saying 'Here you are kid'. However, my mum had drummed it into me to never eat anything that someone else had bitten into, so I shook my head and said, 'No thanks'. He continued holding out and eventually one of the other boys noticed and came running over, saying 'If she doesn't want it, I'll have it'.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

I was going to mention. They had prisoner of war camps situated in the hills above Greenock and you could go up there and actually talk to prisoners. And the prisoners used to make toys to pass their time so it was quite a thing. I remember I got made a boat, a wooden boat, by one of the prisoners. And I don’t know if we paid for them in any way whatsoever but I know that they were delighted to do them and hand them over. And it never occurred to us that these were the enemy, you know. It certainly didn’t occur to me. I didn’t look upon them as enemy. I wasn’t quite sure why they were locked up. But I think some of them were allowed to wander around you know. I don’t think they were chained in any way. I think they had quite a bit of freedom.

The ones I remember were Italian. But I understand there were German ones, but certainly Italian ones are the ones that I can remember. And of course, we had the whole of the West of Scotland Italian Cafés and ice cream shops. But it was funny, most of them got rounded up and so you had Italians that were actually prisoners that were given a certain amount of freedom and the ones that had their shops were in some cases taken away.

I think most people were very grateful to the Italian Cafés and Ice Cream Shops because there was very few places where you would buy them anywhere else. Coffee, I mean that was the first place you were introduced to coffee. Although it was horrible. When I think of it now, the coffee they sold was dreadful stuff especially when you were growing up as teenagers. It was quite a thing to be going into the Italian Cafés for coffees and sitting for hours, you know, with the one coffee. Maybe if you were really flush you could afford to get another one.

David McNeice, born 1937, brought up in Greenock and Millport

In Comrie, there was a P.O.W. camp called Cultybraggan Camp 21, and there they housed 4,000 German Nazis, hard core stuff. So, as an adult about twenty years or so ago I came in contact with one of them who lived in Phoenix, Arizona. And I went to Phoenix, Arizona to meet with him. His name was Helmut Stenger and he was a boy of 17 back then. But he looked at Adolph Hitler the way I looked at Baden-Powell. Because I was in the Cubs at Hillhead School as well as the 84th Glasgow Scout Troop at the Church at the corner of Gibson Street.

Helmut would tell me all sorts of tales. He was in a U-Boat and the U-Boat was bombed.

I’ve got his story written down in my website which is www.highlandstrathearn.com and in there is a chapter called A German Friend, and it’s also followed by the death of Wolfgang Rosterg, he was murdered by his own people at Cultybraggan.

As it became much more obvious that Germany was going to lose the war the German P.O.Ws were allowed out of the camp to help the local farmers for example with planting and reaping the crops. And he was befriended by his first girlfriend, his first love.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

During our time in Gosport she [his Mother] would take me with her as she sold war bonds and she would go knocking on doors around Gosport dragging me with her. I was such a cute little boy, long curly blonde hair. Anyway, she would take me around town and introduce me as ‘this is Eenie, my youngest son. But anyway, she did so well, she sold so many war bonds that she actually received an invitation to go to Buckingham Palace. I think it was in ‘48. So she went up to London, I think it was the Queen, the Queen’s Mother’s garden party at Buckingham Palace. I still actually have the invitation she received. So of course, she imagined she would be on her own meeting the Queen Mother, but she was just one of thousands who had done a lot of war work and this was their reward.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

She wasn’t a seamstress [Grace’s mum] but she knitted socks for the troops. Now I don’t know how she got them away to them. And I don’t know whether she used new wool or whether it was ripped out garments. But she did knit socks and she could talk to you…with her four needles. She could turn the heel in the sock without thinking about it. She seemed to be knitting… Most evenings she would be knitting. And it was socks for the troops.

Grace Wilson Blair, born 1935, brought up in Shotts

I remember seeing G.I.s. They used to go about the street chewing gum and the game that we had was you had to run up to a G.I. and tap his collar and say ‘Any gum chum?’ I don’t know what age I was. And invariably they would give you a wee bit of gum or whatever it was they were chewing. That was my one chance at talking to a G.I.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill