Children of all ages helped the war effort during WWII, in a multitude of ways, both in a paid work capacity and on a voluntary basis. Small children throughout the UK knitted squares of blankets for soldiers. This happened in schools in Glasgow, where teachers taught children to knit and explained why the blankets were important for the war effort. The squares were then sewn together into blankets by members of the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service. Children also helped with ‘dig for victory’ schemes at home and at school, where plots of land were often dug up for the purposes of growing vegetables. An estimated ten thousand square miles of land had been dug up and planted in the UK by 1942. Children often helped to maintain ‘pig bins’, which were food scrap bins created to feed the pigs that people were keeping in gardens or on areas of waste ground, all done as part of the dig for victory movement. Six thousand pigs were kept in gardens and communal areas in the UK by 1945. Not all children enjoyed this work and we have found one account of children tying trip wires to pig bins in Glasgow that, once tripped, would result in adults being covered in rotting food from the bins!

Families and children from the cities had been casually employed to pick labour intensive crops, such as berries and potatoes, since the 19th century, when the Great Hunger in Ireland and the Industrial Revolution, amongst other factors, caused the numbers of farm workers to fall. Of course, children had always helped to help out on the farms and to bring in harvests, but as compulsory education was introduced, school holidays were centred around peak agricultural periods when children’s efforts were essential to securing good food supplies. In Scotland, fifty-four thousand children helped to plant and harvest the potato crops during WWII, alongside the Women’s Land Army (which recruited members from the age of seventeen), and with the assistance of prisoners of war (POWs) and travelling people, etc. Children often got time off school for this work; others would have been over the age of fourteen and employed to do this work. Certainly, older children would have had to help out if their family owned a farm, which was true of some of our project participants who, when teenagers, spent many weeks planting and harvesting crops on their parents’ farm. This was no doubt replicated across the country, along with children working in all types of family businesses, especially in the wake of staff shortages.

Boy scouts collected wastepaper and scrap metal to help with shortages. They also functioned as stretcher bearers, messengers, and general helpers during the Blitz. Girl guides travelled to the Scottish countryside to gather berries to make rosehip syrup, an essential source of vitamin C, and to collect wool from fences, and they also collected old saucepans (for the metal content) and jam jars to be recycled. This helped plug the gap in resources caused by German blockades at sea. Guides also helped during air raids and with supporting evacuees. Those that were too young for enrolment to war service turned up to help in hospitals, often tending to badly injured people in the course of their work. Both the scouting and guiding organisations helped raise money for the war effort.

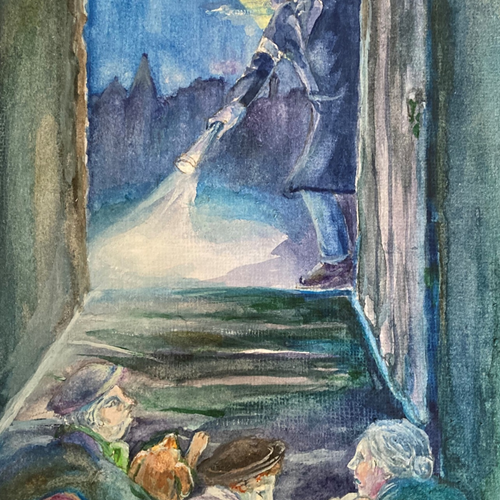

During the war, children could leave school at the age of fourteen to go to work. Many of those children worked alongside men and women in armaments and munitions factories; this was extremely risky and tiring work. Many children had more than one job or took on additional roles on a voluntary basis; some worked through the night with the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) service, or with the Local Defence Volunteers. As of 1941, all those aged between sixteen and eighteen in the UK had to register for some form of national service, even if they had full-time work. One teenage boy who worked with the Local Défense Volunteers in Renfrewshire remembered how he came face to face with Rudolf Hess having a cup of tea at a farmer’s house, next to the field where he landed his plane. This boy reported that cycling round the countryside, armed, was an exciting part of his war, even if he did often fall asleep at his desk at school the next day! There is anecdotal evidence of boys in London and Birmingham helping the ARP at ages as young as fourteen, by, amongst other things, operating sirens and acting as messengers, across bombed out and burning streets, when telephone lines went down. Many wartime children reported that they felt safer and more in control than if they had had nothing to do whilst the bombs were falling. Some found this work exciting. Boys and girls also joined the Air Training Corp (ATC) and other forces’ youth groups. Sadly, there were fatalities amongst this age group whilst working in these dangerous occupations. A boy who was working as a messenger for the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) in Glasgow, was blown off his bike and killed by the detonation of a bomb. He was one of many children hurt or killed in the course of their duties nationwide. Another important war-time job was carried out by boys as young as fourteen years old - delivering telegrams by push bike or motor bike to give people both good and sad news of relatives. We know of another boy who did this in the West End of Glasgow and Maryhill at fourteen. Many reported that the job made them grow up fast and that it was often very harrowing.

WWII did not stop children’s capacity to enjoy themselves and they played many different games, both in groups and individually. The most popular games were often cheap and traditional. Outdoor games included hopscotch, skipping ropes, and all types of ball games – football, rounders, cricket, netball, skittles, and bowling, etc. Street games were also popular, with many children enjoying red light/green light, bulldog, hide and seek, statues, and tig. Building dens, either outside in gardens and woodland, or indoors, under tables and beds, was great fun, and resulted in many blankets, cushions and pillows being temporarily repurposed!

In the days before television and video games, youngsters’ indoor pastimes consisted of playing house, school, soldiers, or Cowboys and Indians, or with dolls, cars, or marbles. A simple cardboard box would become a baby’s cot, a castle, a fort, a palace, an army trench, or a hidey-hole. Children also loved to play board games, either with friends, siblings, or adults. Here, ludo, snakes and ladders, chess, draughts, Monopoly, Scrabble, and dominoes whiled away many hours, especially during the winter or cold damp days when it was too wet to play outdoors. Playing cards were another favourite, and games were often played with siblings and parents. Happy Families, snap, go fish, hearts, pontoon, and queenie, gin rummy – the list goes on!

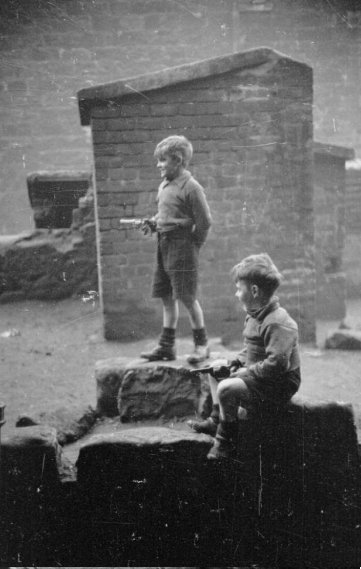

A group of boys from the deprived Gorbals district of Glasgow play among the gravestones of the Corporation Burial Ground in 1948 Other children play with toy guns

Childhood Memories

“Children’s Work and Play”

We made our own entertainment. We used to get cardboard and you all had your own wee space on the railings. And you put cardboard and string and that was your horse. You couldn’t win because you’re all in a straight line but we’re shouting come on, come on. Then we’d shout ‘Throw me down a piece’ and all the mothers would throw pieces down and we didn’t have to go up for anything and off we’d go again (on their horses).

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

James Love, middle row, behind the boy sticking his tongue out. Mix of Protestant and Catholic friends. 1951, near Ibrox Park

You never heard us saying bored. We never were bored. Because we lived at the end of the glen. There’s a lovely glen in Old Kilpatrick. We used to play in it and go picnics in it and there was rope swings in the trees. And swings and roundabouts. So, if it was dry at all we were always up the glen having picnics. Or down the shore when we were a wee bit older. Ten and eleven maybe we’d go down the shore and light a fire and roast potatoes. We were always out. Even in the rain. But more so in the dry weather.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up in Old Kilpatrick

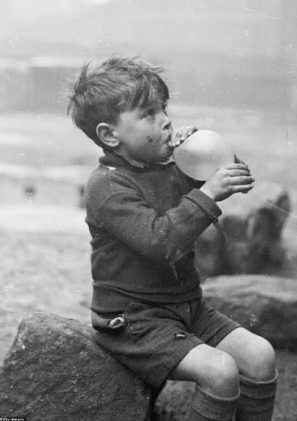

Kenneth MacAldowie, aged 3, at home in Aberdeen

On Coronation day I got bored with the television and the kids, we were all about eight or nine. Were out playing cricket in the street using a gatepost as a wicket. I got interested in cricket because of my blind grandfather. Coronation year as well the Australians were over and he used to listen to the ball-by-ball commentaries. And I used to sit with him and listen too. I played cricket right up until my thirties and started playing tennis.

The other things that we did, we used to build bogies, wood with old pram wheels and there was a hill where we were, it was a cul de sac, so we were able to go down the hill in the bogey” (added by respondent) - Description of bogies, a plank of wood 5/6 feet with cross struts nailed or screwed at front and rear and four pram wheels attached at each corner the front cross strut being able to be turned left and right.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

Where I lived, you never saw children out playing with toys. When I went out to play I usually took a ball to bounce against the wall. I was only allowed out to play during the summer school holidays. Sometimes if it was a nice day, we would walk to Kelvingrove Park which took us nearly an hour and have a picnic. Our picnic consisted of whoever was luckily enough to scrounge an empty bottle from the house and fill it with water from the tap. Then we each had to sort of scrounge a jam piece to eat. On the way back from the park we'd stop off at a shop and hand in the bottle and get a penny for it which was redeemed for probably a strip of liquorice or something to share with the others.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

And Glasgow Green that was a big, big part of ma childhood. That was more or less my playground. And they’ve still got the drying area there and they use to go to the wash house. The drying area. Praying for a good day (laughs).

Grass. You used to run away down the grass in your bare feet. You just tumbled and tumbled and tumbled and chased each other and tumbled. What else could you do, steal the flowers? Just in front of the People’s Palace there was a bit that you weren’t allowed in. We would creep in there and there was Rhododendron bushes. We would hack them away and then you’d hear the parkie coming and run like hell. You would take them to the teacher for the altar. She must’ve known where we got them, we were all torn to hell (laugh).

It was just great I mean, there were swings there and a kind of gymnasium thing. We always tried to reach it but we couldn’t reach it and there was what we called the sawny pond. A wee bit of water and sand. It must’ve been filthy I don’t know how we survived (laugh).

You played in the streets. You played Rounders and you played Doublers, and you played Kick the Can. I didn’t like Kick the Doors Run Fast. I think that wasn’t awful nice. I didn’t like that. Oh, there was so many different things and sometimes the Mothers would join in. They would come and hold the skipping ropes. They were probably only young women and we thought them old. And it was a wee bit of their childhood coming back again. We had a great life in the London Road, you could see everything coming up and down.

There was a whip and peerie. And there was a shop that hired out bikes. They were old wrecks but it was great. You could play in the street because there wasn’t a lot of traffic then. You would hear about a side street that was good for the skates you know. You didn’t fall off and get all grazed.

Anyway, I’m still here, I’ve survived, playing in all the muck, playing in the middens, a lucky midden. I’ve survived it all and now they can’t stand germs now. I think I’ve got a built-in immunity or something like that.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

You played at either a wee house or a wee shop. If it was a wee shop, you always had to have things to sell. So rather than risk the wrath of your Mother for taking anything out of the house we used to get things out of the middens, out of the bins. And of course, people didn’t just throw their rubbish out then, and there was no bin sack. It was you took your bucket down and emptied out the whole lot and also your ashes out of the grate. So if you wanted to get tins or bottles or anything out of the bins you ended up covered in grey ash dust as well. I remember how inventive we must’ve been. Because if you were playing at a shop and you wanted to weigh something. you would find a brick or a reasonably square stone and a bit of wood and on one end. You would put another stone so that it tipped up and you would weigh things on it. I can’t remember what we used as so-called money. I’m sure it was just little stones. Backcourt concerts that was the thing where people used to sing and dance in the backcourt. I think it’s very sad now that society’s not safe enough for children to enjoy the freedom that I did as a child.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

Yeah, we played a form of cricket where you marked a wicket on the side of the bomb shelter and we played Rounders. That was a very popular game. And there was a version of Blind Man’s Bluff, which was a street version of that. I do recall that. And we also played some tricks on neighbours whereby you would tie a rope from one neighbour’s house to the next one where there was a bell. Then you would pull the bell and run like hell and wait for the neighbours to come out and say, ‘Who’s at our door?’ I don’t know how often that happened. And then Halloween was a big event, turnip lanterns and so forth, so that was another form of a game. But that was an annual event, probably still is. Commercialised now I imagine.

Party Piece? Oh yes, when you went around guising you had to do something before you were given some sweeties or something. You had to say a poem or sing a song or if you were musical play your violin or something like that. So you went around, that was part of guising and I guess that’s changed somewhat too. It’s terrible the way that it happens over here (USA). Kids just going around with bags of stuff and expect people to throw things into it. So it certainly was nothing like that. We probably didn’t get very much either.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

Gordon Gorman as a cowboy who had hung his gun up on the table, circa 1958, at 125 Parson Street, Glasgow.

We played with friends either in the street or in gardens. We lived in a relatively quiet part of Aberdeen and we went to the park. Also, grandparents were close by within a mile and you would walk. And when I started school at Robert Gordon’s College and it would be about a mile.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

Leisure activities at home in these days were mostly card games, Pelmanism, Whist and Patience. We also played board games such as Ludo, Snakes and Ladders and, later on, Monopoly.

Back in Glasgow outside games, in Glasgow, were predominantly football played with any strange things when we could not get hold of a ball. Empty tin cans tied up rags and newspapers but somebody nearly always managed to scrounge a ball (mostly tennis balls). We also played cricket in the summer with wickets painted on the wall of the Kelvin Hall and usually with an old tennis racquet, a shovel or just a piece of wood and a tennis ball. Ball games were not allowed in the Street and we needed to be alert for the local Bobby. ‘Kick the can’, ‘Hide and Seek’, ‘Dodge the Ball’, ‘Peever’’, ‘Marbles’ and ‘Tig’ were also favourites. We also spent a lot of our time climbing on the washhouse roofs and the walls separating our backcourts from the next street’s. There was ice skating in the Kelvin Hall on a Saturday morning that I went to for a few years around 1946-48 and we roller skated with skates which were clipped and strapped onto our shoes. Although nearly all Glasgow streets were cobbled there were areas in front of the Kelvin Hall and the Art Galleries and a single street not far away that were smooth.

We sometimes went fishing, with nets, to Whiteinch boating pond where there were small fish known as baggie minnows. We collected caterpillars from the leaves on the holly trees, which at that time were planted around the Kelvin Hall, and we caught wasps and bees in jam jars until finally the cruelty of all this dawned.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

A memory that stays with me to this day is of the first Christmas tree I remember, which had real candles on it and wee prancing horses. We had them in the family for years. I can also remember a Christmas present of a wooden block with nails and my own wee hammer which my father said was the present that I played most with. I have been hammering things ever since.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow

There was a company called "Hornby" who made toy clockwork train sets and we all had them. We marked the underside of the rails with different paint to know whose was whose. One summer’s day we built a tunnel between two of the boys’ gardens. Disaster! The tunnel and the wall began to collapse. Our regular window cleaner, who was a friend indeed, got some cement and brick and repaired the damage before parents came home from work. One year we had a circus where we all had to do an act. My wee brother was stationed on the gate and took the entrance money. I do remember that it was a very warm sunny day with all the mothers in frocks. We had so many things to do. There was Victoria Park just down the hill from us. We could go on the paddle boats for tuppence or go on the play park swings for nothing. As we became a bit older, we would have a go on the tennis courts. Every activity was always packed full. There was also a very good public swimming baths called Whiteinch.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow

Most of the children kept within the law. The lawbreakers were in the main adults. We got on with playing cowboys and Indians, pirates fighting for hidden treasures, playing chases, kick the can, swapping comic papers, collecting cigarette cards and other activities. Cigarette cards were very educational and interesting. They covered a variety of subjects such as steam locomotives, racing cars, aircraft, ships, birds, flowers and the colour printing was of high quality. There was one card in a packet of cigarettes. A complete set comprised fifty cards for each subject covered. In order to try to attain a full set you would have to swap (exchange) the duplicate cards you had with another boy who was collecting the same series. On a weekly basis we swapped comics. We were devoted readers in those days. The comics were not only picture stories but printed stories. The standard of reading was high. It has to be remembered that there was no TV and many households did not have a radio. After evening teatime, you could expect a knock on the door and one of your chums would be there when you opened the door. He would have a selection of three or four comics to exchange if you had not already read them and he had not seen yours. It might seem unhygienic when it is known that paper carries germs, but apart from the usual childhood illnesses we survived.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

Back in Provanhill Street there was chores to do. Some jobs I detested. The worst job, for me, was when I had to take the latest infant out in a go chair or pram. This was the pits. My pals would be free to play while I was virtually anchored to the pram. How I disliked it. But that was the penalty for being the eldest of a growing brood of children. When I look back, I realise that my mum needed a break and I was the only one available to look after the younger kids. Any pocket money I received I earned. One of my jobs was to polish the copper hot water storage tank in the scullery. When we moved into the house the tank was a dull, reddish-brown colour. Within a month it was polished, with the aid of Brasso, to a high brilliant shine, like a mirror. I got a penny for that. I also learned to scrub linoleum floors. My mum showed me how to darn holes in my socks, as she did not have time to this herself as there were now five kids, so she had her hands full. She needed someone to take some of the work load. There were times when I felt an absolute drudge. A few years later, however, this housework experience came in handy when I was called up for the army. A major part of the duties in the first six months on training consisted of “housework”. I was able to avoid the wrath of the duty sergeant because I got the cleaning chores right first time. It was surprising just how helpless some of the lads were when it came to cleaning the barrack room. They were even worse when it came to darning socks and keeping their kit neat and tidy.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

We had a lovely childhood in a Glasgow which has had lots of people knocking it but it was a place of wonder for me and my pals .We played the same games in the street as our mothers and fathers had, albeit we had bikes which most of them did not have. I don’t think I mentioned that the film "Ben Hur" had a great effect on us as we built bogies of various shapes and sizes and raced them round the block pulling them with two or three bikes. What glorious smashes we had on these. There were not nearly so many cars then and we did not have anything more than scrapes. Myself and another chap were into building home-made cannons/muskets. When I finally succeeded in my cannon, the old man put a stop to all further experiments. This let me safely approach 1960, leaving school and getting a job. My youthful days were more or less past.

Colin Stevenson, born 1944, brought up Hillhead and Jordanhill, Glasgow