By the time World War Two broke out in 1939, much had been achieved in terms of improving health. There were more beds available in hospitals and there was wider access to health care as the health system began to function more efficiently. However, there was still much more to be done, especially in the case of infant mortality and child health. Prior to the break out of war the infant mortality rate was high, despite falling by a third in the period 1901-1921, due to the depression of the 1920s and 1930s. From the 1930s onwards, the infant mortality rate was 17%-18% higher in Scotland than it was in England and Wales. Diseases such as diphtheria were rife, with 15,069 cases being reported amongst children as late as 1940, and the continued existence of squalid housing in urban areas of Scotland, and the overcrowding it promoted still had to be addressed. Of children who were evacuated during the war, 31% were found to have been infested with fleas and lice, and scabies were common. However, during World War Two many of these problems were addressed and, as a consequence, the health and diet of the population improved and many of the anomalies in terms of access to health care disappeared.

In wartime industrial areas of Scotland, overcrowding and bad housing conditions, as well as uncontrolled development, and city smog, were the worst enemies of public health. The work and responsibility of local doctors and health centres were increased tenfold as children’s playgrounds became insanitary backyards and dirty pavements. Despite this, health was improving due to an increase in health and welfare provisions for both children and adults. Firstly, there was increased attendance at antenatal clinics offering early diagnosis of illness as well as parent craft classes, which made women more confident in terms of child rearing. Maternity and obstetric services also improved with the introduction of the mobile maternity unit, which was available for women in their own homes in the case of an emergency or complications; this helped to improve infant mortality rates. At no other time in history did children receive more medical attention for their wellbeing. Mothers were able to take their infants and toddlers to child welfare clinics, where they could have their development monitored by experts to ensure they did not suffer in later life. Nursery schools were introduced and not only did they free up mothers’ time for war work, but they also instructed children about personal cleanliness, which was essential for health, and staff ensured that kids were being well fed. Schools introduced medical services and rolled out immunisation programmes to protect again the scourge that was diphtheria. As well as this, school meals catered to the dietary needs of growing children, and milk was provided in classrooms. There was also an increase in health provision for adults at this time. Factories introduced regular medical check-ups to ensure workers were not overly-strained, as many were being left near to physical and mental exhaustion due to working long shifts. Some workers also had access to specialist hospitals where they could go to get rest and improve their health, though many more of them burnt out and their families suffered the loss of a loved one.

WWII children eating healthy carrots on sticks

Various organisations and schemes helped to improve health during World War Two. The Emergency Hospital Scheme began, in 1939, as a scheme for expected civilian casualties in air raids, with seven new hospitals being built in Scotland, and annexes being built onto existing hospitals. Contrasted with their Whitehall counterparts, Scottish civil servants had experience of running health services in the Highlands and Islands. When the air raid casualties did not materialise, the hospitals were put to effective use and a whole new range of specialities were established instead, such as orthopaedics, neurosurgery, and psychoneurosis. In January 1942, another health improvement scheme was set up, ‘ The Clyde Basin Scheme’, which was a unique experiment in preventative medicine. Round the clock shifts had left Scottish industrial workers on the brink of mental and physical collapse, and prevention was deemed to be better than cure to maintain the war effort. The EHS provided an additional 20,500 hospital beds, which was a 60% increase on existing provision. From pre-war bed shortages, Scotland by 1948 had a relative abundance: 15% more beds per head of population than England and Wales, and Scotland also had 30% more nurses, and was already better resourced with GPs.

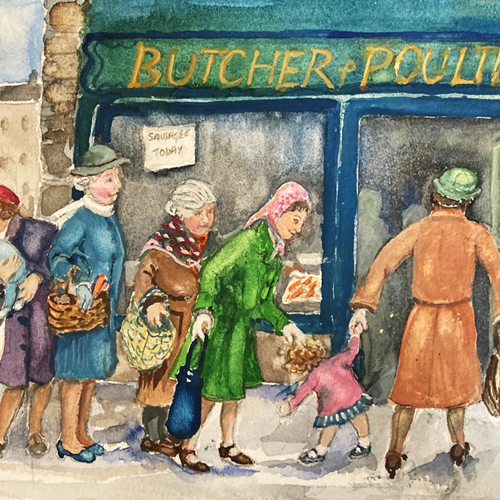

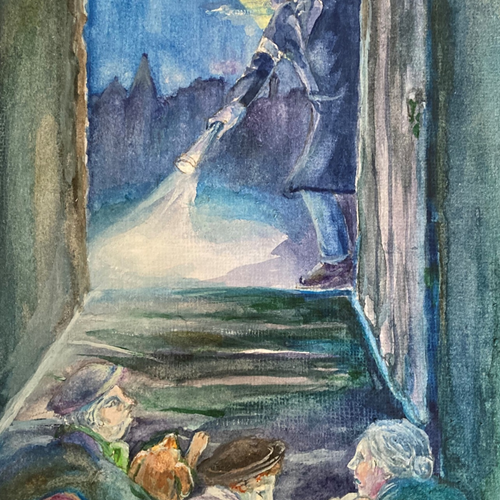

‘Smog’, by Joyce Kelly, Artist in Residence, Communities Past & Futures Society

Other UK wide schemes were set up to improve the health of the children and these would have had an impact on Scottish children. Unfortunately, children were especially vulnerable at this time to health problems such as head lice, skin disease, and poor nutrition caused by the rationing of food, clothing, soap, and footwear. It was a major challenge to prevent poor health as with war came shortages of certain staple and nutritional foods. However, there was a surplus of certain foods, such as carrots, which led to a campaign by the Ministry of Food in 1942 called ‘Mr Carrot, the children’s best friend’, which encouraged children to eat a better diet to help maintain their health. During rationing, children received more eggs and milk than adults and were encouraged to eat more fish, vegetables, and fruit. Due to higher wartime nutritional standards and easier access to medical treatment, the infant mortality rate fell during the Second World War to a fifth of the 1901 level. Efforts continued towards the end of the war, and into the post-war era, when the welfare state improved the social fabric of urban areas beyond recognition, particularly in housing. As a result, health indicators showed a vast improvement with the most sensitive of all, infant mortality, falling by 89%, or from 70.4 deaths per 1,000 births to 27 over this period, which was a remarkable achievement. However, there was no room for complacency as the west central region of Scotland, in the early 1950s, still had the highest child death rate in any region of the UK. Although there remained discrepancies in terms of life expectancy between social classes, the battle against the disease of poverty had been virtually won by 1950; the battles against the diseases of affluence were about to begin.

Childhood Memories

“Home Remedies”

If you had a cough she rubbed you with Vick, back and front, or she would give you a good spoonful of Angier’s Emulsion it was called. You don't see it nowadays obviously it’s away. On a Friday night after getting my hair all washed with the nit comb. It was murder it just about took your scalp off. And then she gave you a dose of syrup of figs. And you had that before you went to your bed on a Friday night. She always gave you something if you had a cough or whatever. She looked after us well even though she was on her own.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

My Mother used to pour some cod liver oil down my throat, big spoonful’s. I remember when we moved up to the top of Ellisland Avenue and going out to school. I don’t know what you’d call it. It was like a kind of heat thing you’d put on your back and chest and it was that hot you’d have melted.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

There was Vicks on the chest and my Mother used to think that M & B, which was the first antibiotic, was absolutely magic. M & B was the answer to everything. I suffered from boils at one stage. And I’d been to an outward-bound course and my Father had suffered from boils when he was in the Air Force. And he used to have a poultice with Epsom Salts and Glycerine (Added in by respondent) that would draw it out. I don’t think you’d be allowed to do these things any more, you get Penicillin. I remember getting some Penicillin injections. And the other thing I remember, while still in Aberdeen, was I got some teeth out, because my mouth was overflowing. And it was gas you got for that and I felt absolutely dreadful. While I was in my second year at school, we were playing football and someone tripped me and I fell against the wall and I broke a front tooth. Fortunately, the master I had first period was a chap Donald Mack who taught history and he had suffered similarly. And it was a Friday afternoon and he said, ‘You get to the dentist now, if you don’t do that your weekend is going to be sheer purgatory’ and I got to the dentist and it was filled. I had gold inlays and then crowns.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

I can remember my mum and aunt taking turns to stand on a kitchen chair and have a black line pencilled on to the back of their legs with an eyebrow pencil. We didn't have shampoo. We washed our hair with a brownish coloured soap called Derbac. It had a strong disinfectant smell. In a tenement we only had a range which was kept burning all day and all the cooking and heating of water took place on it. It also had an oven on the left side for baking and roasting. So, to wash your hair you usually put a saucepan of cold water on to warm up and poured it into the basin in the sink, refilling it so you would have warm water for the rinse, with vinegar being added to the water in the basin. I had dark brown hair and the vinegar was supposed to give it a shine. Late in the 1940's, mum one day brought in some sachets of shampoo she had bought in the chemist across the road and it was powdered shampoo which you put in a cup, added enough water to dissolve it then washed your hair.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

A poultice. It was like torture. My chest used to bother me a wee bit with the smog and that. It was torture. Thank God I didn’t have any hair on my chest, it would’ve took it off. I think the poultice had mustard, vinegar, a secret recipe.

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

I can remember getting poultices on skint knees which were probably poisoned. I remember having a carbuncle in my arm and I remember my Mother putting poultice after poultice on to it. We were always pretty healthy because we were taking omega 3 before it became popular. My Grandfather used to get Scott’s Emulsion for us which was made from cod liver oil. I loved it. You always knew when winter was coming because my Father would get Halibut oil capsules and we’d to take one a day and also rosehip syrup. We also used to get syrup of figs on a Friday night. Oh, and I hated it, and I can still taste that to this day.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

We were an extremely healthy family as far as I can remember. But one of the things I do remember is a particular ointment for an itch or a rash that we would use in the family. And it was called Dr Lawson’s Ointment and it was invented by my Grandfather. And so, when you went to the local chemist, all you needed to do was ask for Dr Lawson’s Ointment and we’d get this ointment.

Helen Jean Millar, born 1931, brought up Pollokshields

My Grandfather was always in the herbalist shop. And I can remember little small white pills, they were the cure for everything. I can remember the herbalist shop in Glasgow. It was in Dundas Place and we used to go there. We used to have pease brose. It was like a powder and you could have it for breakfast and you mixed it with hot water and then you had milk with it. And we did get that a lot. We used to make Senna tea, you could buy Senna leaves and make tea. And at the coal fire it was in a big enamel jug to keep it warm. So they could have this once a week to keep you regular.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

It was almost like witch-doctoring in those days. I can remember my Mother would give us sulphur and treacle supposedly to purify the blood. Yes, it was every bit as bad as you can imagine. I was given hot milk with a raw egg in it, which to this day I don’t drink milk, almost never. We had things like Askit Powders for headaches. I mean in those days they would actually, if you were sick, would give you whisky with warm water or honey or sugar in it. It didn’t matter what age you were they would just do it. They’d give you alcohol.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchape

Oh yes, Rosehip syrup was one of them. A little whisky on your gums when you had toothache. There was also some kind of cough syrup that they gave you.

A hot toddy was a cure for some colds and I remember my Mother…there wasn’t enough whisky at the time, and my Mother sent me to a neighbour to get a little bit of whisky. I don’t think it was me that was getting the hot toddy but it may have been, and I went to a neighbour and I came home with it. It was probably for my Mother because she would’ve gone there herself. I was going to make it for her, I said I could make the hot toddy and there was very little whisky. But I boiled it and so we had no whisky. I never lived that one down.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

My Mother was tea-total, but she always kept a bottle of Advocaat indoors. She truly believed Advocaat had a medicinal purpose. You’d use a poultice for a boil. If you had diarrhoea, you got a bottle from the chemist or the doctor, kaolin and morphine, Codeine for a headache.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

Poultices. I think it was bread that they made a poultice with. They strapped it on to maybe draw poisons out or something like that. Liquorice, Tree Root and Epsom Salts.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

In 1944 my mother contracted tuberculosis and went into Robroyston Hospital where she remained until just after war ended. Nana (what I called my grandmother) visited her every afternoon, taking me with her. We went on a bus. T.B. patients were housed in sort of Nissen type huts with verandas around them. Children were not allowed in so we had to sit in the gatehouse with the Gatehouse Keeper who made sure we all behaved ourselves. I remember an older boy showing me how to fold a hanky to make a rabbit and a Christmas cracker, which I can still do. Sometimes we played games like snakes and ladders, ludo and card games like snap. Visiting was only for an hour. My grandmother would take cakes and other food for my mum as food in the hospital was very basic. On my 5th birthday, I was taken up to where the huts were and was about 20 feet away from the door of the hut my mum was in when she came and stood by the open door and waved to me, shouting happy birthday. In 1945 mum came home clear of T.B. She had been in there about a year. It did leave a mark though. From then on, she had her own towel and facecloth. Also, her own cup. She seemed terrified of me contracting the dreaded disease as well, even though she was cured, and from then on I was fed daily doses of cod liver oil in the winter and later she discovered a malt extract which came in a big jar. God knows how many of those I consumed over my childhood years. I only had to cough or sneeze in the winter and I would have my feet in a bowl of hot water with mustard powder in it. I would also have extra clothes on to make sure I kept warm when I was at school. If I did get a cold - well is was a Kaolin poultice on my chest which I hated. The Kaolin was in a tin which was put into a pot of water to heat up, then was spread on a piece of old flannel and sort of slapped on to my chest. It was thick and gooey and in the morning it was horrible, as it had gone cold, and I would hurriedly peel it off.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

We all had home remedies. I remember vinegar and brown paper could be applied to your chest if you had a cold. Friar’s Balsam, you would mix it with water and you would have a towel over your head and breathe it in. Vapour rubs of all sort of descriptions. A big penny on your forehead if you fell and bumped your head. Keys down your back if you had a nosebleed. I remember my Mum talking about one of her sisters when she was young having rickets and her father, in order to stop her ending up with her legs bandy, used to make splints and bandage her legs every night so as her legs would be straight. So that was a kind of a home-made orthopaedic remedy I suppose. And she ended up with straight legs. But that was only because of him taking matters into his own hands and doing that.

Marlene Barrie, born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

There was always poultices, a bread poultice, a sugar poultice, a mustard poultice and somebody telling you how to cure something or whatever.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

When I was about 9, mum bought me a toothbrush. Toothpaste came in the form of a powder in a round tin. Occasionally if we had run out, Nana would take my brush, open the little trap door in the range and scoop out some soot with my brush so I could clean my teeth.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

One of them was for a sore throat. Coarse salt would be heated up. My Mother had an old fashioned bed warming pan on a long handle and they used to put the last coals in that at night and run it over the sheets in the bed to keep it cosy. Well, they used to put salt in the pan and put it under the grate in the fire and then using a scoop they would put roasting hot salt inside one of my Father’s socks. And that would be fastened round your throat and it actually helped. I mean it was amazing. The Kaolin poultice was another one. The tin was heated, spread on fine material and put on to your chest. If you had toothache a tiny piece of bandage wrapped around a clove was put on the tooth that certainly helped as well.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

I remember having scarlet fever and my Mother running down to get me some ice cream because it was thought to be helpful for someone feeling a bit of fever. Well, I enjoyed the ice cream anyway.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

I used to have a problem where my fingers would get poisoned. I don’t know how it would start but the finger would end up full of poison so it would end up being poulticed. Poultices I do remember because they were very hot and quite painful but it did work.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

In 1944 my mother contracted tuberculosis and went into Robroyston Hospital where she remained until just after war ended. Nana (what I called my grandmother) visited her every afternoon, taking me with her. We went on a bus. T.B. patients were housed in sort of Nissentype huts with verandas around them. Children were not allowed in so we had to sit in the gatehouse with the Gatehouse Keeper who made sure we all behaved ourselves. I remember an older boy showing me how to fold a hanky to make a rabbit and a Christmas cracker, which I can still do. Sometimes we played games like snakes and ladders, ludo and card games like snap. Visiting was only for an hour. My grandmother would take cakes and other food for my mum as food in the hospital was very basic. On my 5th birthday, I was taken up to where the huts were and was about 20 feet away from the door of the hut my mum was in when she came and stood by the open door and waved to me, shouting happy birthday. In 1945 mum came home clear of T.B. She had been in there about a year. It did leave a mark though. From then on, she had her own towel and facecloth. Also, her own cup. She seemed terrified of me contracting the dreaded disease as well, even though she was cured, and from then on, I was fed daily doses of cod liver oil in the winter and later she discovered a malt extract which came in a big jar. God knows how many of those I consumed over my childhood years. I only had to cough or sneeze in the winter and I would have my feet in a bowl of hot water with mustard powder in it. I would also have extra clothes on to make sure I kept warm when I was at school. If I did get a cold - well is was a Kaolin poultice on my chest which I hated. The Kaolin was in a tin which was put into a pot of water to heat up, then was spread on a piece of old flannel and sort of slapped on to my chest. It was thick and gooey and, in the morning, it was horrible as it had gone cold and I would hurriedly peel it off.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

Childhood Memories

"Smog"

They were awful, and you used to put a hanky in front of your mouth and put a scarf around it. And when you took the hanky off it was absolutely black. The air we were breathing in must’ve been horrendous. I remember one night my Mum had sent me to elocution, something else that didn’t last a long time, and I’d gone down for this elocution lesson and the smog came down. Now we would all have been about 8 or 9 years old, and it was down so thick, you literally could not see your hand in front of your face. So the teacher just opened the door and let us all out into the night to find our way home. Really it was just awful, and I was walking, and I knew I was going in the right direction but it was quite scary on my own walking along. It was just horrible you couldn’t see anything. And then after I’d been walking about ten minutes, I bumped into somebody coming the other way, and it was my Mum. She was coming out to try and find me because she knew what it would be like trying to get home in the fog. I was so relieved to see her and then the two of us tried to make it home together.

Marlene Barrie, born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie

The pea-soupers were particularly bad because there was a lot of industry. There was a lot of chimneys, I remember that. And because we were at the top of Sandbank Street you could actually look down and see how low the smog became. And I remember being taken out at bonfire night to hold the sparklers and watch the bonfire. They used to have a bonfire near us in Gilshochill and everybody just went to this ground and watched it. And that night it was particularly bad, and my Mum had put a scarf round my face. And I remember getting back to the house and blowing my nose and all this black like soot.

I remember the smog made everything look quite eerie. The street lights looked green. There was an eeriness about it. I think most people had a wariness about going out because they couldn’t actually see where they were going. And I remember the tram cars they would crawl along when there was a smog. Because obviously they would be worried about hitting another car or hitting someone. But they were particularly bad in the early ‘50s.

Heather Bovell, born 1948, brought up in Gilsochill, Maryhill

Yes, up into the middle ‘60s. The Clean Air Act certainly made a big difference. And the buildings that were coated with the smog were cleaned up. When the smog came down, fortunately we lived in Dumbreck, and I was able to get the underground. But I had a scarf round my face, and it was black by the time I got home. But that was really the last bad one.

I did suffer from bronchitis as a boy. Whether that was the smog or age. I grew out of it. And I haven’t been bothered with it since. But I know of others who suffered badly.

Kenneth MacAldowie, born 1944, brought up in Aberdeen and Glasgow

We got the train from Portsmouth Harbour Station which was a big excitement for me. On the train to Waterloo and then we went across on the underground to- I think it was St Pancras or Kings Cross for the Glasgow train. The Royal Scot. It was all very exciting for me. I had all my puzzle books with me to go on the train. I had my puzzles, which were those interlocking puzzles that you played with. So, I had plenty to do on the journey. Anyway, we got to the outskirts of Glasgow and the train slowed down and we gradually shuffled into the city. And my Mother looked around and there were tears in her eyes. And I remember this. And the reason was that she loved the south. She loved Gosport. She was actually from Yorkshire originally. So she realised what she’d given up in coming up to Glasgow. But of course, in those days wives followed their husbands, where the job was. The train moved in and Glasgow was a dreary looking city, soot blackened and not that long after the war. Anyway, it looked pretty miserable. All the while my Mother did not like Glasgow. Eventually when my Dad died, she moved back to Yorkshire and finished her days there. So that was our introduction to Glasgow. My Dad loved it. He was very friendly my Dad and he got on well with everybody.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

I remember one in particular, and we came out of Rutland House in Govan Road. And it was one of those where you couldn’t even see the bus. London had them as well. When I say pea-soupers- you wouldn’t go out in a car on your own. So the passenger would just be looking out trying to see the pavement. And lucky in those days there weren’t many cars so there was nothing parked. And sometimes you had to stop because there was nothing to tell you where you are. You’d lost the pavement. They were diabolical in Glasgow and London, really, really bad.

Philip Cohen, born 1937, brought up in the Gorbals and then Shawlands

I remember many times if I’d been out dancing, or I’d stayed late to work, and I would take either the train home or the bus. Sometimes, especially with the bus the fog would come in really thick, and it would only go so far into Dumbarton. And you had to walk about a mile in the fog. Usually there would be a kind gentleman that would walk with me. They all knew my Father. He’d worked in Dumbarton for so many years. And they would accompany me which was very kind of them. I remember them very well. It was so thick. It was almost scary on the train.

Rene Walters (nee Catherine McMenamin), born 1938, brought up in Dumbarton

Sometimes you couldn’t really see in front of your face it was so bad. If you blew your nose, everything was black. I remember you washed your face and maybe the water had run down, so then you had little clear bits and your neck was absolutely grey. What do you call them - tide marks?

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

When I was working. I used to work down town in Gordon Street in Campbell’s Whisky, opposite the Central Station. You’d have on your nylons and if you had a ladder in one. When you got home you had a black line all the way down your legs because of the smog. And your face would be all dirty.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

I think I would mention the terrible smog and industrial fogs that we had in Glasgow, that were pretty fierce. And I remember one time on the bus coming home from the centre of town and the smog/fog was so thick that the conductor of the double decker bus had to walk in front of the bus. Because the driver couldn’t see the kerb because it was so thick. And so we crawled along like this until I got home and walked up the road. And got home and washed my face. And I remember seeing a line of soot coming down from my cheek through my nostrils where I was breathing in this smog. And so this was what people had to endure. And of course, was very bad for health. And I’m afraid Glasgow lungs were not very pretty things when they were being examined.

The buildings were very black. There was a terrible environmental problem then which then disappeared. As coal burning stopped and it gradually disappeared. It’s no longer an issue. But it’s certainly something you can remember very clearly of these times.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

We also used to get fogs, yellow fogs because of the industry that was all about. They used to have sales in the shops afterwards for things that had fog damage. It was yellow, yellow fog and it made a mess of things. You couldn’t see an inch in front of you sometimes. That went on up until the ‘70s even. I can remember being stuck up in Balloch, where I was teaching, because the fog was so thick, the buses weren’t running. That was common. The blackout and the fog.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

It was terrible, it was really bad. No wonder so many people died. It was so thick you really couldn’t see your hand in front of your face…The worst one I saw was when I was working in Manchester coming out of work one night. And it was terrible… in fact the bus we were on couldn’t go any further and we’d to walk.

They were pea-soupers. Really thick because of all the coal burning all the time. It was absolutely horrendous. Glasgow was just black. And it’s only recently they’ve started to clean up the buildings after all these years. And it’s the same with Clydebank.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

People to this day in Glasgow call them fog. But it wasn’t natural it was industrial smog. It was absolutely awful. I mean it was so bad that it would slow traffic to a crawl and my Father had decided he wanted to get a small moped to go to work rather than take two buses. So, in the Winter when they had these temperature inversions the smog would just be grey. You couldn't see out your window. My Mother would be a nervous wreck because he was trying to drive home in this terrible weather. I remember coming home from school on the bus. Because I went to high school in the city. And it would be like night time and the bus would be crawling along trying to find its way. I mean you’ve no idea how bad it was. Eventually, in the ‘60s, they introduced what they called smoke control acts. And a lot of that improved. But in the ‘50s it was awful.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

I remember walking home from my work and you walked on the tram lines because that was your guide to get home. I remember walking along Alexander Parade on the tram lines. My underskirts were black and it was up my nose. If people had a car someone would walk with a torch to give some guidance to where they were going. So, it was quite horrific. I can remember going to my work and there were lots of traffic jams at the end of Alexander Parade and Castle Street and the bus would be sitting there for ages. When you worked in the Telephone Exchange, I wouldn’t say they didn’t believe you, but if you were two minutes late they would phone the Bus Company to see if the bus was late.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

I remember that, oh yes, pea-soupers. During the winter smog in the early days was a real problem. You could taste it; it was just horrible. Even covering your mouth with a scarf you’d get the taste and the smell of the chemicals in it. It was pretty horrible stuff. It could sit there for days and just wouldn’t move. But you just had to get on with it, making your way to school, keeping your hand on the hedgerows as you went along, hoping you didn’t bump into anybody and listening for cars. Fortunately, in those days there weren’t very many vehicles on the roads, so it wasn’t too bad. The only bad road I had to cross when I was younger was Great Western Road. Which I suppose was quite a busy road even then. And it had trams running up and down the middle of it. So, I can remember them. But you could always hear them coming.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

I’ll tell you a story the smog. I used to play chess for Hillhead High School, and we were playing in the Southside. I think it might have been Shawlands Academy. And the chess match always started round about five or six o’clock and always finished about eight o’clock. And on one particular evening where there was heavy smog coming down, we got there, but everybody left separately. And I knew if I took twenty-five steps out there, and turned sharp left for another twenty-five steps, there would be a bus stop there and right enough. And coming towards me after about twenty minutes standing waiting on the bus, a bus came along with a man leading it in front with a flash-light, a torch. And of course, the bus driver had his lights on, so I figures, oh that’s great he’s going to take me to Bridge Street, I think it was, there was a underground station, a clockwork orange type of thing. And that’s what happened. But on the way to Bridge Street the fellow was out there with the torch and doing his thing. The bus was moving about half a mile an hour and then they discovered they were on the wrong side of the road. That’s how heavy-duty smog could be. When I got from Bridge Street to Kelvinbridge, I virtually had to hang on to the railings on North Woodside Road to get up to Park Road. And at Park Road I fundamentally put my right hand out on the building feeling my way along until I came to Gibson Street. Then turning right and going up to Otago Street, and then crossing. And I got home about ten o’clock at night or something like that.

That was the worst experience I ever had in smog. Pretty dramatic stuff actually. Fortunately, today, that’s all gone.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

It was really bad. You had to wear a scarf. When you came down the stairs and walked across the road to get to the railings where the wee school was and find your way round. It was almost like blind man’s buff.

My Granda, my stepgrandad, Billy-Da he was Irish, and we lost him. Hinshelwood Drive was a circle as I said, and he kept going round the wrong way and turning. Then we found him and took him home.

There was a tram depot right beside us in Ibrox. And you used to see them going in the fog but they were lucky because they went on rails and they had a lamp. And I think the conductor sat on the front of the tram, shouting get out the way, get out the way.

The smog didn’t help, there was a lot of chest infections and lung problems and the works like the Galvey, lorries with asbestos. And the smog just added another layer to that and of course it was industrial trade that was causing the smog in the first place. So what a hard life they had. You just couldn’t get out the bit.

James Love, born 1943, brought up in Craigellachie and Glasgow

I remember if it was a foggy night, and you were coming home, you didn’t have a car or any luxury like that. You had to go on the bus and then walk the rest. And by the time you got home the insides of your legs were black and your underskirt…you used to wear an underskirt, no trousers for ladies then, and it would be coal black, really filthy dirty by the time you got home. It was terrible. I don’t remember anybody wearing masks. Sometimes they used to walk out in front of their cars. And you’d see somebody with a torchlight walking in front of a car to show the driver the way. There were some real pea-soupers we would call them. But it made everything filthy. And then after that they went on to no-smoke coal or something.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside