The lack of consideration towards contextual factors during the Second World War is limited in terms of research, particularly the impact the war had on education. This section will explore the educational gains and losses that occurred as a result of the Second World War.

The transportation of urban children to rural areas caused great difficulty for teachers and children alike. Those who were from cities, such as Glasgow and Edinburgh, had lower academic ability than those who were from the countryside. In 1939, Roderick Barron, H.M.I., stated that in relation to primary education, children in rural areas were far advanced in terms of reading and writing than those from cities. The contrast between both groups provided difficulties for teachers and the mental-wellbeing of children. The Scottish Educational Journal (1944) stated that the war had a greater impact on children from the cities. Those who were from the countryside still had the ability to obtain pre-war grades, whilst those in cities were falling further behind due to a lack of confidence in their learning. This was further emphasised through children’s behaviour as they began to compare themselves to a group who were academically progressing whilst they were not. The urban group was described as inferior and having a lack of ability, in part due to a study conducted by A.D Dunlop in 1941; he concluded that children from cities were a year ‘ retarded’ in their reading abilities. Whilst the attention for teachers was primarily focused on improving the ‘ inferior’ children, the ‘ clever’ children had to teach themselves; however, this did not impact them negatively, as D.M Mcintosh, assistant director, stated that clever children were doing even better than before the war.

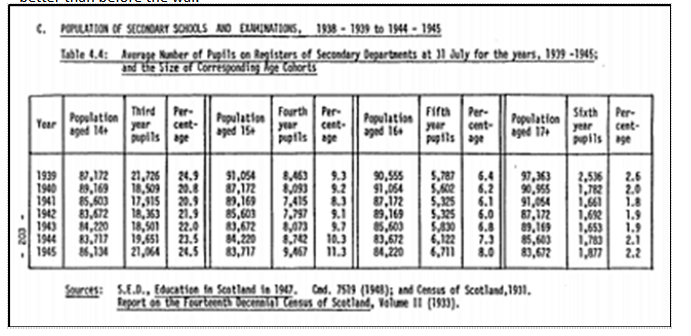

Secondary educational standards did not decline but the want to attend secondary education did. Education did not seem important to many children ( mostly young boys) when there was a war going on. The lean of labour to the war efforts resulted in the classes of junior secondary children rapidly declining in size. The chance to gain economic prosperity at such an early age appealed to many boys, and the war efforts was believed to be their chance to set up for the future. However, economic motives were not the only reason for early withdraw from education; women, too, left to support their family through the dark times of war. Husbands and sons would have been enlisted to fight for their country, and it was up to the mother and older children within the family to keep the family united and afloat. This impacted women’s academic progress significantly. Prior to the Second World War, most women who were academically gifted would have progressed until sixth year, and then later continued their studies at university level. The overall wartime situation was believed to be a considerable loss for education, as prior to the war there were around 5,700 thousand fifth year pupils, this dropped significantly to 6,122 in 1944. (Report of the Fourteenth Decennial Census of Scotland, 1948). Further evidence to support the loss of education due to the Second World War was that only 2% of the population in 1945 attended sixth year studies; therefore, wartime efforts largely effected children’s chances to prosper in education. (Summary Reports, Census 1948).

Those who left not due to economic motives or family support, often did not care for their academic progress. Attendance during the Second World War declined and in some cases was non-existent. In Ayrshire, six years prior to the outbreak of the war, the average attendance for secondary schools was 91.6%; however, from September 1941 to June 1942, a thousand children each school day would not attend school for reasons that were not considered as excusable prior to the war. Attendance in Glasgow schools began to deteriorate at the start of the war and declined each year until 1944 (Glasgow Education Committee, The War, 1939-1948).

Evidence strongly supports the theory that Second World War resulted in education being negatively impacted. Firstly, the war resulted in children from cities being identified as inferior in terms of learning; this was concluded through comparison to rural children they had to learn alongside due to evacuation to the countryside. However, this can actually be seen as a positive too, as without the evacuation to the countryside as a result of the war, the lack of progress city children were making academically may have never been identified; this knowledge allowed this anomaly to be targeted during and after the war.

Furthermore, the evidence shows that the Second World War limited educational prosperity for many children, as young boys’ attention was diverted to labour or military work instead of education, this led to an increase of dropout rates at the junior school level. However, this was not gender specific as women also felt the pressure from the war, and often decided to drop out of school to support their family whilst their father and brothers were away fighting on the war front. This is viewed as largely detrimental to educational prosperity, as most of the women who dropped out due to the war would be the type of individuals to go onto university education and perhaps than make a notable difference within society.

Undoubtedly, the war overall resulted in a lack of attention and worry about academic progress or academic importance. It resulted in a shift of priorities for most Scottish individuals; young boys wanted to fight alongside their fathers for their country, and young women wanted to support their family as best as they could whilst their menfolk were on the war front. Children’s priorities were not to prosper educationally during this time but to support and help the war efforts. Children may not have been able to academically prosper during the war, but most did grow up sooner rather than later. Whether this was beneficial to them in the long term is up for debate.

Childhood Memories

“WWII Education”

Just before we left primary the girls were taken into a class and told about periods and that was it. That was our sex education at school. And we came out and the boys all wanted to know what you’d been told and of course nobody would tell them. So that was the sum total of our sex education. Most things were learned from pals, older brothers and sisters. Probably even my parents weren’t that confident about speaking to you about those kind of things.

Marlene Barrie born 1946, brought up in Scotstounhill and Blairdardie.

Our school wasn’t too far from the house. My Mother would walk me there initially. I remember my very first day actually being five and that would be 1947. And it’s still clear in my memory. I remember going into this cloakroom just outside the class and there were all these other kids with their mothers and an awful lot of them were crying, yelling and clinging to their mothers’ coats. Because they didn’t want their mothers to leave basically. But I, it’s not that I didn’t love my dear Mother. This was quite a whole new experience for me and I was quite interested in what was going to happen next. So eventually we got into the classroom and started to knock the pegs into these things with a wooden mallet. And also do some drawing and open up picture books and things like that. There was another time I remember seeing a picture of a horse. The first horse I’d ever seen was in this book. And also an elephant, and the elephant reminded me of this barrage balloon.

There was one Sunday I remember I was a lead choir boy, lead chorister. And we walked down one afternoon with the Provost leading the pack. And the fellow with the cross up front. And we all had our white surpluses and red cassocks. And we actually processed down Great Western Road between churches. And, of course, us choir boys we would hold up our hymn book to try and hide our faces from the trams and the buses that were going by. Because we just didn’t want anybody at Hillhead High School to know what we did on the weekend. So nobody found out.

My claim to fame was one day I was chosen for the second fifteen at the high school. Not the best team, the second fifteen. And we played Dalry Academy. It was a bitterly cold day so we took the bus out to Dalry. And during the course of the game there was a point at which I was the only guy between one of these bruisers in the other team and the touch down. And I can remember my pals down the other end of the pitch shouting ‘Coomie, Coomie, get him Coomie, get him Coomie’. And I had to get this guy and he was quite a bit bigger than me. Anyway, I had to stop this guy and I didn’t want to do the regular standard rugby tackle which was to grab him by the ankles and bring him down. Because I was frightened, he would kick me in the face. So, I jumped up and I grabbed him around the neck and he carried me down the field a few yards. And eventually he fell and I dragged him down. And I held him on the ground until my team mates came up behind me saying ‘Well done Coomie.’ So I was a star for a very short time. I mean on Monday, that was it, I was a star. I stopped this guy from getting a touchdown. But that was my only claim to fame when it came to sports. The rest of the time I was singing in Church.

Ian Coombe, born 1942, brought up Gosport, then Glasgow

No sex education whatsoever…The way I educated myself in this was purely by accident. I came across a book at home. I was a young teenager, and it was called ‘Wanted A Child’ and it was a sort of self-help manual. Probably from the ‘40s. Which I think was given to couples probably to help them figure it out. It basically explained all of the information that you need basically. So I’m thinking that my parents’ generation didn’t really get any help from their parents either.

Murdo Morrison, born 1950, brought in up Scotstoun and Drumchapel

I went to school at the age of five and a half and I started school in January because of the way the birthdays fell. So I spent two and a half years in the infants at Hillhead Primary School. So we had the afternoons for the first six months and then mornings until we finished the infants. I remember getting a halfpenny special on the lunchtime tram, that’s what it cost at lunchtime for children. And a penny in the morning and afternoon. Hillhead Primary School in those days was a grant aided selective school. You had to have a psychological examination and I can remember it quite clearly. And I can remember my Mother told me quite clearly. If you smile up at the psychologist, who had a great big nicotine-stained walrus moustache. And all the other children wailed and ran away. But I didn’t want to go with him. And he said, ‘och she’ll get in’, so that was quite fun.

In secondary school when we couldn’t go to hockey at Hewenden when it was raining. And we were closeted in a class. We would get the health book to copy bits out of. And it told you a little bit about sex there. And also about the kind of shoes that were better for your posture. But no we didn’t get sex education.

Christine McIntosh, born 1945, brought up Hyndland, Broomhill and Arran

A story that sticks in my mind is that one day she was turning round to write something on the blackboard and her underskirt fell down (Mrs Rose) on to the floor. And of course, the kids laughed uproariously at this. And she was very calm about it and just picked it up and put it to the side as if nothing had happened. But for kids that was great fun. So that was one of my school memories.

At school there was rugby and cricket that you played, and badminton and I had the honour of getting the Glasgow Schools Championship. We won the final of the Glasgow Schools Championship and we got the Wilkinson Cup for the school. And I remember playing in the final against a couple of lads from St Aloysius that were in the final so that was badminton. I played that at school. There were other sports too. But I played badminton and cricket and played rugby up until I was maybe fourteen. I was too small and it was a sport for larger and brawny people. So I started playing something more safe like tennis.

Hugh Livingston, born 1940, brought up in Hyndland and Fintry

Yes, I saw that on T.V (The Coronation). I remember the Queen came to Glasgow one time and all the school children turned out on the streets. We were all taken out the school and all had to line the streets and wave to her as she went by. That was in the elementary school, I remember that.

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson, born 1937, brought up in Glasgow and Fintry

(Winifred) Margaret Baker Davidson at primary school, second row up, second in from the left

I loved school. Well, I loved primary school. I would have stayed there forever. The teachers wiz great and it wiz… Some people had a hard time. When I look back on it. What they done. You know. I always think of all these boys. They were pushed up the back. Mostly it was boys. Pushed up the back o the class. And every now and then they would fire a question at them. And if they didnae answer it right or something then they got whacked again. Course we were a giggling. See when you look back on it…They boys could have been deaf. Maybe they couldn’t see properly. Maybe they couldn’t hear properly. And they made out as if they were daft. You know. God help them.

Cabreg, born 1935, brought up in London Road, Glasgow, and Pollok

It was alright, it was quite strict really. There was no nonsense and what the teacher said, that was It that was law. We used to get out to play at playtime and had good fun with your friends. When playtime was coming up they brought in milk and we were allowed a wee tiny bottle of milk with a cardboard top. And you pushed the wee thing on the top and put the straw in. So we got that every day and that was free. It enabled you to have some energy for running about at playtime.

M. McKinnon, born 1937, brought up Govanhill and Southside

Well, I went to school in October 1945. The big high gate was closed at nine o’clock when the bell rang. I think we had a better schooling but then it was more organised and people accepted what they were told to do. Because I do have five grandchildren and I can see the difference in schooling.

I’ve been lucky because most of my family did go on to university. I didn’t because I didn’t want to in the first place because all your pals were leaving school so you left school. I think things were different then because you only went to university if you had money and could afford to go.

Marion Penny, born 1940, brought up in Townhead and Ruchazie

When we were evacuated, I went to Kinghorn School for about a month. But then one of my young Aunts was killed in a motorbike accident. So the police came to fetch us and we had to come back to Old Kilpatrick. Then after the summer they built huts in the playground. So we finished our schooling. The infant department was still standing but the primaries four, five, six and seven were in huts in the playground. But the school opened after the summer and we were able to resume our education…When we were at school quite often there would be an air-raid. The sirens would go, but the teachers would just take us down to the shed, it was under the infant department. And we’d play games until the all-clear went and then go back up to the classroom. Again, I don’t remember anybody being scared or panicking or anything.

You would get threepence in the pound for gathering rosehips. So, the whole family would go gathering rosehips. My Granny was the best at picking rosehips. You took them to the school and they got weighed and you got threepence for every pound that you had collected. Some families would come in with about ten pounds or more. We usually had a modest amount, but it was great fun going picking them.

Elma Robertson, born 1936, brought up Old Kilpatrick

I went to Garrioch Primary School in Maryhill, Hotspur Street. It was just round the corner. Some kids had play-pieces. A play-piece was just like a wee sandwich and sometimes it was toast and it was in a wee paper poke, and you got eating that at playtime in the mornings. Maybe about half ten when you had that wee fifteen-minute break. I think that was to give the teachers a chance to have a cup of tea and a smoke. We were just out in the playground whether it was raining or not. I used to come hame for my dinner because I only lived round the corner and I wouldn’t have got free dinners anyway, because my Father was working. Some kids got the dinner hostel as we called it. And some paid for their dinners. I used to envy them, because they used to tell you what they got for their dinner.

The teachers were all old. They were all about seventy, or looked about seventy. They were all older than your Mother and Father anyway. The teachers in those days were teachers. You did what you were told. They were good. I never disliked any teachers. I think there was a lot more respect. The kids were frightened, but not terrified. If they didn’t behave themselves, they got the belt and I got the belt a few times. It was reasonable. It was fair, it was fair.

I went to what was called in those days North Kelvinside Senior Secondary. That was for the stupid but saveables (sic). East Park was for the ones that weren’t as clever. If you were exceptionally clever the teachers would put you forward to sit a test for a bursary award. And then if you passed that you went to Allen Glen’s, which I think was one of the top schools in Scotland. That was for the really clever ones. My cousin went to there.

I left at fourteen because I wasn’t fifteen till the August. So, I left during the school holidays in 1963. That’s when I left the secondary school.

Sandy Boyle, born 1948, brought up Maryhill

In 1943, when I started school, we carried gas masks to and from school but this did not last long I presume because the danger from bombs and invasion had considerably lessened. My Father grew vegetables, potatoes, carrots, cabbage, lettuce, peas and tomatoes in two greenhouses in the garden in Milngavie, both while we were evacuated and for many years after we returned to Glasgow, since Mr Anderson gave him expenses to travel out and maintain the garden and gardening was his hobby, He also, in the years after the War, attended to his Mother’s large garden at her house in Lesmahagow. I also did some tree planting with one of my teachers, in a garden by Woodside Secondary School around about 1952. One of them still stands and has gotten big. We never got moved to other buildings, in fact schooling for me, did not change after the War.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie

I went to Kent Road school and used to take a tram to get there. It was only about a fifteenminute ride. For some reason my mother didn't want me to go to Washington Street school which would have been about a fifteen-minute walk along to Anderston Cross. Kent Road school had two buildings, with the infant school being the building at the back. The headmaster was Mr McConachie and he walked round the school in his long black gown carrying his tawse. He was fanatical about singing and you would be in your class half way through a lesson and he would barge in and tell the teacher to bring us out into the hall where the rest of the infant classes were. We would sit down and the piano in the corner would be rolled forward and the music teacher would be instructed to play with us singing. I can't remember what we sang. Every year there would be a school concert at St. Andrew's hall and Mr McConnachie was always on the lookout for pupils who had any musical aptitude or could dance.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

I started at Knightswood Primary when I was five. I do remember I didnae want to come home on the first day. You know you had to go home at lunchtime. You only went in for the morning and my Granny came to get me. And I was in a bit of a strop because I’d made so many friends and I didnae want to go home. But I think I got over it. The older I got, the less I liked school…It was a big old wooden school and I remember my first teacher, although I can’t remember her name. But I remember she wore a long sort of pinny dress. She was quite young and she was very nice.

I remember there was an old railway line with some sort of engineering works at the back of it near the school. And a steam train used to pass the school every lunchtime taking trucks from the engineering works further over back into the main lines at Anniesland. I can remember that because all the boys we used to hang about the railings and wave to the trains that passed. And the men would wave back and blow the hooter.

Graeme St Clair, born 1947, brought up in Knightswood and Springburn

Miss McGhee had some work to do one day. She had to have peace and quiet. She told the class that there would be a prize of two pence for the pupil that was the quietest during the following hour. We had been told to study our reading exercise books and not make any sound. It would be a very difficult thing for thirty children to remain quiet for ten minutes let alone sixty. I resolved to be as quiet as possible. I read my book and when I got bored with it I thought what I could do with the money. You could buy 10 caramels for a penny. It cost a penny to get into the Carlton Cinema, Castle Street. If you went there at 4pm for the afternoon matinee. Comic papers were a penny or tuppence. These thoughts were occupying my mind when Miss McGhee called us to attention. The hour was up. We waited with bated breath to hear who had won the prize. She said that the class had been very good and that there had been little noise, but the quietest class member was John Power. I might have blushed. I went to the teacher’s desk and she handed over two pennies. I thanked her and returned to my seat trying to ignore the looks of envy from my classmates. What to do with my wealth? That was the question. One of my pals was Hugh Huston. It was a Wednesday and the matinee was on in the Carlton. There was a serial adventure with Bela Lugosi, who always played the villain and the hero was Bruce Bennet. The heroine was of no importance as us chaps thought that the romantic stuff was cissy. Hugh accepted my invitation and we both ran all the way, about half a mile, to the cinema. A grand time was had by both of us.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

Occasionally we would have to line up in the hall and were each handed an apple and an orange. Britain used to receive fruit from abroad - Canada I think- which was solely for the school children. When I moved up into the senior part of Kent Road, we lined up one day and each got a banana. We had never seen one before and weren't quite sure what it was. I took mine home and ate it there.

Evelyn Humberstone, born 1939, brought up Argyll Street, Glasgow

I remember the writing materials (laughs) It was a slate. I don’t know if you’ve seen them or heard about them. And there probably about nine or ten inches by about five or six inches. And it was slate and you had a bit o chalk. And that’s what you wrote down yer…I was never good at writing or spelling or (laughs), cause we’d no paper, you know. Even though that was after the war. You still…that’s how bad things were, you know.

James McLaughlin, born 1939, brought up in Clydebank and Rothesay

I went to Willowbank School and was there for six years. And then passed my examinations and went to Hillhead High School. And I was at Hillhead High School for four years but it wasn’t a particularly happy experience, other than the pupils that were in my class that I befriended. And I still know quite a few of them. And I see them when I go to Scotland.

Peter McNaughton, born 1944, brought up in Clapham, Glasgow and Comrie

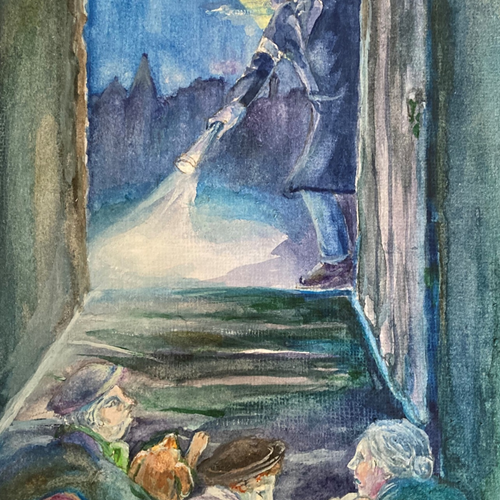

It was at this time that the government order was issued which made school attendance voluntary because of the threat of air raids. The R.A.F had taken over part of the school playground for use as a base for a barrage balloon unit. This consisted of a large, camouflaged truck equipped with gas cylinders, a deflated barrage balloon and a winch with a reel of cable. Once on site the servicemen would fill the balloon with gas while it was attached to the winch cable. When fully inflated it looked like a big fat whale with three fins at the rear. It was released on its cable to float at a suitable height to prevent enemy aircraft from flying below a certain altitude. The idea, I suppose, was to reduce the accuracy of aircraft weaponry. A number of balloons were shot at by enemy aircraft and they would ignite, being filled with nitrogen gas. The balloons were also left up at night as a hazard for enemy bombers because they would be invisible.

I have to confess that I took full advantage of the rule regarding voluntary attendance. I played truant. I would leave home at the customary time and meet some of my classmates. We would discuss our plans for the day, and either hang around the back courts where the bricklayers were building bomb shelters, or go to the fruit market in the hope of finding some fruit, except bananas were not imported during the war. I spent about ten weeks doing this until the order was rescinded and school was again compulsory.

John Power, born 1927, brought up Saltmarket and Garngad, Glasgow. Courtesy of his daughter Dini Power

School. I thought it was quite nice. Baby class, you had…the tables were painted pink and all that. And you had to be well behaved. Everybody was well behaved. I don’t know why but they just were. But I could read before I went to school. Cos my Mother used to read Black Bob out the Weekly News. It was a sheep dog, Black Bob. And she would read books to me. Anything. And I would quickly spot-you missed out that bit you missed out. So eventually I just learnt to read. So, when I went to school, I was quite bored. They would maybe give you a book ahead or something. But it was still kinda boring.

I hated milk. They used to give us a wee bottle of milk every day. Quite good if you liked milk. That was another good thing you were getting. Probably helped the kids that weren’t getting fed properly.

Cecilia Murray, born 1942, brought up in Gorbals and Castlemilk

I went to nine schools between the ages of 4 and 11 so you can see that I wasn't at any school for very long. Always the new girl. I loved the fact that you did some exams and moved up a class if you did well. I think Scotland had the best education system in the world at that time. I loved school dinners I think they cost about ten pence a week-maybe 1/10. I can’t remember.

I loved school it was my escape from whatever drama I was living. At one time I attended Bearsden Academy and thought it very posh. I started my schooling at The Hermitage in Helensburgh at 4. I upset my mother because I wanted to go to school on Saturday. Teachers were quite firm to say the least but looking back very fair-to me anyway. I left before the Qualifying so have no idea about what happened next.

Matilda Jane Holmes, born 1937, brought up in Clydebank, Helensburgh, and other places

I noticed no change in schooling after 1945 as compared to before. I know leaving age was raised because my Father left school at 14 and, the earliest, I could leave would be 15. Compared to today the Janitor was a big man in the School appearing in all our photos and being responsible for all maintenance work in the school, including defrosting frozen out door toilets in the winter.

Schooling was different from now in that great emphasis was placed on memory and learning the multiplication table ‘off by heart’ without any understanding of the maths involved. We were often given word which we had to learn how to spell and were frequently tested. In fact, one teacher gave us a spelling test each day and where you sat that day depended on how you did in the test. The best sat at the back/right desk and the worst at the front/left with the rest graded along the rows right to left and front to back.

Jim Smart, born 1938, brought up in Glasgow and Milngavie